Creating the Space Force to counter China and Russia answered a rising threat. Now investments are needed to ensure space superiority.

The first Space Race began in October 1957 with the Soviet Union’s successful launch of Sputnik, the first man-made satellite to orbit the Earth. From its inception, funding that Space Race was never a problem. Despite numerous early failures, the urgency of the challenge fueled continued funding because the consequences of losing were so grave.

Now the United States is engaged in a new Space Race, part of a broader great power competition that pits the United States against China not only in space, but in every military, economic, and technological domain. Yet unlike the first Space Race against the Soviet Union, which came hard on the heels of a world war and then another bloody fight in Korea, most of the American public is barely aware of the current stakes in this Space Race.

Most of the American public is barely aware of the current stakes in space.

To be sure, there are differences. From the 1950s through ’80s, when the fear of catastrophic nuclear confrontation was at the forefront of American minds. Today, fear of nuclear Armageddon falls far behind economic and other potential calamities in the popular consciousness. With space becoming a truly open and international domain, enabled by U.S. dominance and American support for the free and open use of space by all nations, China entered this competition aggressively. While losing to China in this great power competition does not necessarily mean nuclear missiles will rain down upon us, the risk of war in space should alert us to other devastating threats: the potential loss of GPS navigation; compromised missile warning systems; disrupted communications and the potential crash of the space-enabled economy; and more. True, this is not the same as a nuclear apocalypse, but that does not mean the effect would not be apocalyptic.

Today, five years after the Space Force was established, fiscal realities are getting in the way of mission. The Space Force’s fiscal 2025 budget will be less than its fiscal 2024 plan, a retrenchment caused by the squeeze on overall Department of the Air Force spending. Former Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall suggested the National Defense Strategy requirements for the Space Force budget require unprecedented increases in spending: “The USSF budget is going to need to double or triple over time to be able to fund the things we’re actually going to need to have,” he said this fall. “Somebody’s going to have to make some decisions about whether to give us a bigger budget overall for this or do some internal trades.”

Absent a major increase in spending, the Space Force will have to constrain its support for some missions, including expansion of new and existing missions driven by today’s rivalry with China and the new emerging threats.

Lessons from the 1950s

The biggest difference between the first Space Race and today is that in the 1950s and ’60s, Americans were genuinely frightened by the Soviet threat and the potential for nuclear war. Children practiced emergency procedures in schools in case of nuclear attack. Fallout shelters were located throughout American cities. The risk of nuclear apocalypse was regularly depicted in books and movies and the Iron Curtain ensured that with few exceptions Americans never saw Russian-made products anywhere. Today, by contrast, Chinese products are everywhere, mostly bearing U.S. and European brands, and the general public is unpersuaded about the risks China poses beyond occasional news headlines.

The most logical threats from China are not nuclear Armageddon. China has been accused of penetrating U.S. and allied phone networks, deploying intelligence tools in cranes at U.S. ports, and manipulating popular opinion through the Chinese-owned TikTok app. Militarily, China has demonstrated capabilities to destroy satellites, and to threaten U.S. forces on land and at sea with hypersonic and hypersonic glide missiles launched from ships, submarines, and fixed and mobile launchers.

Today’s Chinese threat is from space itself. In September 2006 China used a ground-based laser to dazzle or “temporarily blind” a U.S. classified optical reconnaissance satellite. China has at least five sites with directed-energy capability. In January 2007, China launched a ballistic missile from Xichang Space Launch Center carrying a kinetic kill vehicle, which later collided with Fengyun-1C (FY-1C), a nonoperational Chinese weather satellite, at an altitude of 863 kilometers, destroying the satellite and spreading 2,000 pieces of debris that still exist to this day. Then in January 2022 China demonstrated orbital rendezvous and capture capability, when its SJ-21 dragged a defunct BeiDou navigation satellite into a geosynchronous graveyard orbit. While this technology has a clear use in cleaning up space debris, it also has potential as an offensive counterspace/kidnapping capability.

Russia, meanwhile, remains a space power. It too has demonstrated significant counterspace capabilities, beginning in 1968 and most recently in November 2021. Additionally Russia still maintains perhaps the world’s largest nuclear stockpile and operationally demonstrated the lethality of their own hypersonic missiles against Ukrainian targets. Combined with one of the world’s most capable space capabilities, and in combination with other bad actors such as Iran and North Korea, Russia remains a potent and dangerous threat.

Since September 2001, U.S. military investment totaling some $5.4 trillion has prioritized counterterrorism over existential strategic threats. While a pivot to Asia/China was announced by the Obama administration in November 2012, at most, a slow turn. Through it all, China has continued a single-minded focus on overcoming the U.S. as the world’s leader in military might.

Yet in 2018, the United States highlighted “Great Power Competition” with China as our central strategic focus and in 2022, China as the nation’s “pacing threat,” with Russia, North Korea, and Iran as additional areas of concern. Russia’s war in Ukraine, however, has drawn all these players increasingly together. U.S. investment has shifted toward great power competition but we have not yet completed this pivot to a potential conflict that, moving at astounding speed, will require new military capabilities to deter and, if necessary, respond. The shift requires a very different military posture and capabilities than those needed for a focus on terrorism.

That makes today an optimal time to examine mission versus funding—especially in space, where America’s strategic competitors, China, and Russia, are developing space capabilities and doctrine expressly designed to challenge U.S. capabilities and advantages—and for which U.S. countermeasures are not yet fully developed and deployed.

The Space Force was established to define the responses to these threats therefore initial funding levels did not include responses to these threats, meaning funding was set within the constraints of those programs already in existence in 2019 within the Air Force and the other military services. As a result, the Space Force is insufficiently funded to accomplish its expanding mission in the face of growing and changing threats. The formation of the Space Force collected the preponderance of DOD’s space-enabled assets into a single service; it did not provide the resources or means to address the underlying threats that led Congress to press for the creation of a U.S. Space Force in the first place. To date, the Space Force’s budget has remained constrained, both by the competing needs of the U.S. Air Force (within the Department of the Air Force) and those of the other military services within the Department of Defense. The Pentagon’s funding outlook does not match the growing demand for space capabilities from the combatant commands. Soon, the service’s ability to respond to a crisis could be limited.

“The establishment of the USSF was a response to the demands of great power competition in the space domain,” wrote Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman in his “C-Note” #20. “Nevertheless, we still have organizational constructs, processes, and policies that are suboptimized for the great power security environment. Therefore, we must implement enterprisewide changes that can better prepare the USSF for this type of challenge.”

“The United States risks falling behind China in the military Space Race unless they are funded to implement the strategies they have developed to fundamentally transform its space capabilities,” Kendall said in January, a week before his final acts as Secretary. “We are going to need a much bigger and more powerful Space Force … that needs to evolve from the equivalent of the merchant marine to a navy.”

To effectively prepare for great power competition and ensure the nation’s asymmetric advantage in space will continue to enable U.S. joint combat capability, the Space Force will need substantial increases in manning and materiel funding. Without that injection of capital, it will fall short of its emerging strategies.

The Threats

China has developed hypersonic missiles that can be launched from land, sea, undersea, air, and even space itself. Operating at many times the speed of sound, these projectiles can get lost in atmospheric clutter, making them hard to track, and because they can also maneuver aerodynamically without firing engines, they are much harder to find, fix, and track than conventional ballistic missiles, which follow a predictable trajectory. Both Russia and China have also demonstrated direct-ascent anti-satellite missiles, as well as satellites with proximity maneuver along with grappling capabilities to threaten our space systems. Russia has even announced its intent to put nuclear weapons in space.

At the time the Space Force was formed, counters to these threats did not exist. Solutions have since been developed, but to be fielded, they must be resourced.

The service’s budget has nearly doubled in the five years since it was established, but that increase reflects mission consolidation as many space-focused personnel and programs from the Army and Navy as well as the Space Development Agency moved under the purview of the new service. To date, the nation has not fundamentally increased its investment in military space.

The fiscal 2025 budget, which has not yet been finalized, is set to dip, to under $30 billion, as a result of budget pressure within the Department of the Air Force and the Fiscal Responsibility Act, which caps defense spending. But looking out further, Space Force budget documents indicate no plans for rapid growth over the next five years.

“We are maxing out our budget today and seeing a flat-line budget in the DOD,” noted Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. Michael A. Guetlein in a Defense News interview last summer. “It’s got to change. We are seeing a threat that is intent on narrowing the capability gap between us and them. Today, we have margin in that capability gap. If we don’t start increasing our investment in space, we’re going to see that capability gap reverse.”

Expanding and New Missions

In the nation’s first State of the Union Address, President George Washington said, “To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of preserving peace.” Preparing for great power competition means, in part, fortifying our employed-in-place infrastructure in the continental United States against surveillance, interference, and attack.

“Great power competition involves rival nations with global interests, reach, and influence vying to be the preeminent actor in international politics,” Saltzman wrote in his November 2023 C-Note #20. “Great power competition occurs on a global scale. As such, competition between rival great powers unfolds in every domain—most recently in space—and across every area of responsibility. At the same time, most competition between rival great powers occurs below the threshold of open hostilities. Day-to-day, great powers compete for influence and prestige. This is where commitment is tested, resolve is demonstrated, and credibility is established.”

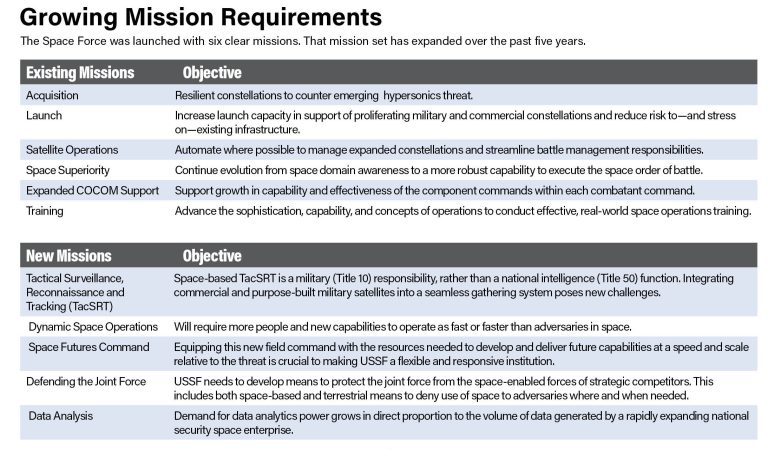

The Space Force must therefore continue to invest in expanding existing missions while at the same time finding the funds to take on new and critical missions.

Growing Missions

The USSF response to threats to U.S. space capabilities includes developing highly proliferated resilient constellations, increasing orbital diversity, and developing the ability to rapidly replace capabilities in event of a loss.

To grow required capability as effectively as possible, the Space Force exploits the capabilities it has, buys what it can, and builds only what it must. The manpower required to acquire, operate, and sustain these capabilities will be greater than what the Space Force can now afford. The developing persistent infrared Missile Warning (MW), Missile Tracking (MT), and Missile Defense (MD) systems to track and counter hypersonic threats require satellites operating at lower orbits in order to detect and track these dimmer threats and report on them at the speeds necessary to enable intercepts. This means large constellations in low- and medium-Earth orbit not just a few satellites, and while these can be smaller and lower cost, the necessary quantity will make this an expensive system. The missile warning/tracking portion would augment the current Space-Based Infrared System, but the greater challenge will be the new mission to provide missile defense support and its associated higher quality of service and global coverage.

A second area of intense growth is launch. Two major factors are driving an exponential increase in launch rates: First, the rapid increase in acquiring proliferated constellations, and second, the huge increase in the support of commercial launches. These increases affect both of the Space Force’s major launch bases:

- Cape Canaveral Space Force Station (CCSFS), Fla. The increase in launches for CCSFS exceeds an order of magnitude increase. The Cape projects a “Spaceport of the Future” to enable launching every day. The launch cadence will likely approach approximately 150 launches next year.

- Vandenberg Space Force Base (VSFB), Calif. The launch rate at Vandenberg, while lower than CCSFB, is still seeing an order of magnitude increase, anticipating 50 launches next year.

As the Space Force adds all these new satellites, its work to maintain and control its satellite inventory will likewise grow by a factor of at least 10. The corresponding increase in complexity of operating satellite constellations will add to the increased workload, as Guardians manage the subtle differences between satellites in the constellations, bring on new satellite capabilities within each constellation, and allow satellites to interact between constellations (e.g. MW/MT to Transport layer). All of this will also increase the scope, complexity, and nuance of required training.

“From a technological perspective, great powers have the resources to field advanced military technologies that increase the tempo, range, precision, and destructive capacity of military operations,” Saltzman wrote in C-Note #20. “Once achieved, however, relative technological advantages are fleeting, since a great power has the resources to rapidly mimic or counter a rival’s advantage. This makes rapidly transitioning advanced technology to military applications a persistent element in great power competition.” As the commercial satellite ISR and communications markets have demonstrated in Ukraine, private sector innovation can be invaluable in military application. The Space Force needs to exploit the capabilities these systems can offer for Tactical Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Tracking. The TacSRT environment is being shaped by a rapidly growing commercial space sector, and the Space Force is embracing these capabilities.

The USSF will integrate a mix of organic, allied, and commercial space solutions into hybrid architectures where the nation’s space capabilities promise to become greater than the sum of the parts. The USSF will leverage the commercial sector’s innovative capabilities, scalable production, and rapid technology refresh rates to enhance the resilience of national security space architectures, strengthen deterrence, and support combatant commander objectives in times of peace, competition, crisis, conflict, and post-conflict.

This strategy is in direct support of U.S. national policy and strategy, including the Department of Defense (DOD) Commercial Space Integration Strategy (2024), United States Novel Space Sector Authorization and Supervision Framework (2023), National Security Strategy (2022), National Defense Strategy (2022), National Military Strategy (2022), United States Space Priorities Framework (2021), and the National Space Policy (2020).

USSF has growing mission areas where the responsibilities are increasing, though the authorizations are not keeping pace commensurate with the current force structure. The space area of responsibility (AOR) is expanding beyond geosynchronous to include cislunar space as the nation pursues the potential for a permanent presence on the lunar surface. With adversaries also pursuing lunar basing and capabilities, space situational awareness and dynamic space operations (DSO) capabilities will have to grow with the expanding AOR, demanding new satellites to support communications, navigation and timing, ISR, and new systems for space superiority.

Dynamic Space Operations

The most critical mission going forward will be space superiority and the ability to defend our space systems and assure they remain available regardless of the attack. America’s adversaries recognize that U.S. combat effectiveness depends on space-based assets, which is why they target our space capabilities in pursuit of their own strategic advantage. Threats include cyber, kinetic, lasers to dazzle or damage, co-orbital spoofing and jamming, and potentially nuclear space detonations, as threatened by Russia.

“There is a lot implied when we start to unpack what we need to conduct dynamic space operations, whether it is on-orbit refueling, on-orbit maintenance, responsive launch, or other ways to achieve sustained maneuver and in-domain logistics on orbit,” Gen. Stephen N. Whiting, commander of U.S. Space Command, said in August at the Army Space and Missile Defense Symposium. “I also think it will become increasingly important to make our space-enabling infrastructure more resilient and survivable. Exploring ways to increase mobility and proliferation will become key facets of the way we envision fighting in 2040. Capabilities to operate in cislunar space, the vast swath of the heavens lying between the Earth and the moon, further will become a SPACECOM mission as NASA and commercial firms pursue lunar colonization and other related activities.”

In the face of such a future, the task of maintaining U.S. space advantages will only grow more complicated, requiring the ability to both assure the availability of U.S. capabilities when needed and, when necessary, to deny adversary capabilities should they threaten U.S. interests. Among needed capabilities will be on-orbit refueling, on-orbit maintenance, responsive launch, and the means to achieve sustained maneuver, logistics on orbit, and ultimately fires. DSO envisions capabilities that complicate adversary targeting challenges by providing in-space capability to change easily predictable constant energy orbits of legacy constellations.

Defending the Joint Force

The space enterprise now needs capabilities to protect the rest of the joint force from the space-enabled terrestrial forces of our strategic competitors. For example, China has built a space-based system to find, fix, track, and target U.S. and allied navies, air forces, and ground forces trying to move through the Pacific and the first and second island chains. This C5ISRT system enables over-the-horizon fires to hold at risk U.S. Navy ships trying to get from the West Coast into the western Pacific and U.S. air and ground forces trying to move within the island chains. Additionally, U.S. GPS signals are constantly under threat of jamming and the satellites that generate those signals are also under threat.

The Space Force must develop the means to defend its own satellites and to hold those of adversaries at risk to guard against the loss of space capabilities to the joint force.

Envisioning what those requirements will be and how to field those capabilities will be the responsibility of the Space Force’s newest field command: Space Futures Command. “Space Futures Command will be responsible for ensuring our long-term technical advantage in space,” CSO Saltzman said in announcing its formation last February at the AFA Warfare Symposium. “What we’re talking about here is nothing less than rebaselining the way we identify, mature, and develop concepts that will shape the service for years to come. This is critical because there are so many things that we need to get right. How do we take in new ideas? How do we test them? How do we align them with the art of the possible, then resource them according to the science of the practical?”

As a baseline, the new command will bring together three centers—the Space Warfighting Analysis Center, the Concepts and Technologies Center, and a new Wargaming Center—to forecast the future operating environment, define the service’s operational concepts, and ultimately “document the objective force” needed for future success.

That force design will drive near- and longer-term funding needs and the mission-by-mission studies needed to craft the Space Force’s force structure for the next 10 to 15 years.

CONCLUSION

In the near-term, Space Force spending is actually moving in the wrong direction. Congress has not approved a fiscal 2025 defense appropriations, so the department is operating on a continuing resolution. But the House Appropriations Committee cut about $900 million from the Space Force’s request and Senate legislation cut around $1 billion. At a point when even if funding were level, it would be inadequate, the Space Force instead is feeling a big squeeze.

Current mission demands suggest the U.S. Space Force is already a $50 billion to $60 billion military service, trying to make do on less than $30 billion. Without sustained funding increases over and above inflation, USSF cannot achieve its objectives, let alone its potential.

Thomas “Tav” Taverney is a retired Air Force major general and former vice commander of Air Force Space Command.