RAF Lakenheath, U.K.

On the night of April 13, 2024, U.S. Air Force crews took to the skies in the Middle East, having received word that Iran had launched one-way attack drones and missiles at Israel.

In one F-15E in particular, pilot Maj. Benjamin “Irish” Coffey and weapons systems officer Capt. Lacie “Sonic” Hester waited for the first signs of the attack, though they were unsure of exactly all that was coming.

Sure enough, “we get a radar hit, and another, and another, and another,” Coffey told Air & Space Forces Magazine. To be sure the blips were missiles and not cars on the ground, Hester cued the jet’s air-to-ground targeting pod to get visual confirmation.

“She recognizes there’s no roads in that area. It’s just open desert,” Coffey said. “So all these radar hits that we get, 20 to 30 of them at that initial [sweep], were real, and they were headed west.”

Those hits represented the leading edge of some 300 ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and one-way attack drones in a barrage that was Iran’s first-ever direct attack on Israel and perhaps the largest drone attack in history.

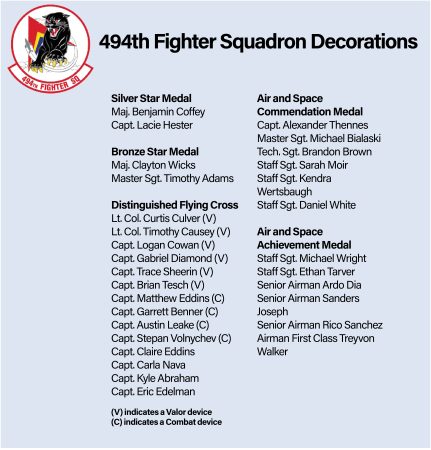

Coffey and Hester, along with other Airmen in F-15E and F-16 fighters, helped defeat the attack, downing 80 drones in one of the largest displays of combat airpower in decades. On Nov. 12, U.S. Air Forces in Europe Commander Gen. James B. Hecker decorated 30 Airmen at RAF Lakenheath for their contributions to that mission, awarding Coffey and Hester Silver Star Medals for their heroism.

The events of April 13, Hecker said at the ceremony, were a clear sign that “the nature of warfare has changed, especially when it comes to … one-way UAVs.”

The 494th Fighter Squadron, nicknamed the Panthers, deployed to an undisclosed Middle East location in October 2023 after Hamas’ Oct. 7 attack on Israel, and over the course of the next five months downed several Iranian one-way attack drones, breaking new ground for the Air Force.

Iran’s drones have been a common feature in Russia’s war on Ukraine, but the U.S. did not have much experience countering those threats, a niche weapon that falls between a missile and air-to-air combat.

Coffey took that experience, “essentially reviewing everybody’s tapes … and then everything he had known and studied,” said Capt. Brian Tesch, a weapons systems officer with the unit. “He wrote a paper of like, ‘Here’s how you will execute if you find a drone out there.’”

Coffey’s tactics development soon proved crucial. Israel launched an attack that killed senior figures in the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps in Syria on April 1, and Iran vowed to retaliate. The 494th braced for the response.

“We were on kind of an alert status for about a week, week and a half, leading up to that point,” said Maj. Clayton “Rifle” Wicks. “We knew that there was going to be some sort of large-scale attack. How big we didn’t quite know, and when exactly we didn’t quite know.”

Anticipating that the attack would likely come at night, the squadron kept at least two jets in the air, plus extra crews on the ground ready to go within 30 minutes. The days dragged on. Then, on April 13, Coffey and Hester were one of the crews scheduled to fly the first six-hour shift, alongside squadron commander Lt. Col. Curtis Culver and Lt. Col. Timothy Causey. Wicks, having flown the night before, was the “operations supervisor,” acting as a liaison with the Combined Air Operations Center and other command and control elements.

“There were a couple nights leading up to that point where we’re like, ‘Tonight’s going to be the night, or we think tonight’s going to be the night,’ and then it wouldn’t happen,” Wicks said. “So then April 13 rolls around, it was kind of like that again. I didn’t show up for my shift that night being like, ‘Tonight’s the night.’”

Capt. Matthew “Pepper” Eddins and Capt. Garrett “Bull” Benner were one of the crews on alert status. They too “didn’t really think much was going to happen that night, to be honest,” said Benner.

Intelligence reports suggested otherwise. Wicks began giving crews whatever new information he got as they walked out the door.

“Things were just happening so fast out there that it was pretty much a sort of a pickup game. … I remember feeling guilty that I couldn’t do more for them, before launching my friends out into the darkness to who knows what,” Wicks said. “So that part was tough.”

The alert crews—Eddins and Benner and Capt. Austin Leake and Capt. Stepan Volnychev—took off with the first scheduled formation, putting four aircraft in the air. F-15s from the 335th Fighter Squadron at Seymour Johnson Air Force Base, N.C., which had just deployed to the region, were also airborne, as were F-16s from the D.C. Air National Guard’s 113th Wing. Wicks was monitoring a command and control feed when the F-16s started to engage.

“A message comes across that just says … like Viper 72 is ‘Winchester,’ which means they are out of missiles. They have no bullets left. They have nothing,” Wicks said. “And I remember, I got chills, and the hair on the back of my neck stood up, because that was the first time I was like, ‘Oh my gosh. Command and control can’t keep up with the amount of missiles that are being shot and things that are happening.’ And that’s the only message they got across.”

In the air, Coffey and Hester were tasked as mission commanders, responsible for multiple “lanes” of airspace that the formation had to defend. Now, they faced an attack on a scale they had never seen before—flying at low altitude into the night.

“I first get hit with dread, recognizing the numbers we were seeing,” Coffey said. “This wasn’t a small-scale or a chest-thumping show of force. This was an attack designed to cause significant damage, to kill, to destroy, and now we are on literally the leading edge of firepower, able to try to do something about that. And that lasted maybe for 10, 15 seconds, and then training kicked in, and it was time to get the job done.”

Confronted with more targets than they could possibly hope to take down by themselves, the aviators started prioritizing the one-way attack drones.

As Coffey and Hester directed aircraft where to go, the other aviators quickly fell back on their training and started executing.

“The first reaction, it was really exhilarating, a lot of adrenaline, especially to finally see the picture that we did see of the tons of radar contacts across the scope,” Benner said. “After that though, once we kind of realized that we were getting into a flow, then it was just fun.”

“As we’re turning away just so we can build some more space from the next wave, you look back and you see drones impacting the ground, like, ‘Oh, they got another one. They got another one,’” added Eddins. “Looking a few miles away, and you see another one’s impacts: ‘Oh, the Vipers got another one.’ And then you hear from your flight lead, Hey, turn hot, so pitch your aircraft back around and target again. ‘Here we go again,’ and it’s just almost repetitive at that point.”

It didn’t take long for every aircraft in the formation to exhaust their firepower. In the span of about 20 minutes, most of the fighters had fired off all eight of their air-to-air missiles. Coffey and Hester had “hung ordnance”—a missile that didn’t fire for one reason or another, and were forced to return to base, while Eddins and Benner waited another 10 or 15 minutes for more fighters.

Capts. Trace Sheerin, Brian Tesch, Logan Cowan, and Gabriel Diamond were the ones set to fly those fighters, having been scheduled for the second scheduled patrol of the night from an undisclosed location in the Middle East.

Soon after they watched their fellow F-15E crews take off and head over the desert, the aviators started to appreciate the size and scale of Iran’s attack. On command and control feeds, they heard that jets were expending all their firepower within 30 minutes, “including air-to-ground munitions, which would be like the last thing you have on the jet to try to take out some of those drones,” Tesch said.

Yet when the crews asked if they would be taking off earlier than planned, the answer came back “no.” Finally, they climbed into their jets. “We had just started the first engine, the canopy had just closed, and then off in the distance, I see about two dozen maintenance folk and other people sprinting and running out of buildings toward the bunkers,” Tesch said.

Ballistic missiles were now either approaching the base, which was close to Israel, or being hit by the Iron Dome defense system.

The base declared “Alarm Red”—meaning it was facing an imminent threat; troops were directed to underground bunkers. A Patriot air defense battery on the base started firing interceptors.

“I look over my shoulder and it just looks like the Fourth of July,” Teach said. “I remember, usually I couldn’t see the paper on my knee because it’s just dark. It’s night. There’s no lighting out there. But I could see, like, clear as day. I could read everything on the paper just from the explosions lighting up the cockpit.”

The second shift of F-15Es weren’t the only Strike Eagles on the flight line. Coffey, Hester, Culver, and Causey, had landed at that point, and Culver and Causey’s jet got an integrated combat turn (ICT)—being reloaded and refueled with the engines running—in a breakneck time of 32 minutes.

But because of the hung ordnance on their jet, Coffey and Hester were planning on hopping over to a second plane when the Alarm Red sounded. With their jet not ready to take off yet, they headed to the bunkers.

Once there, however, Coffey and Hester came to grips with the situation. Their fellow aviators were still defending against the attack—and they had a jet still on the flight line, if they could just get it prepped for launch amid the Alarm Red.

“I remember looking at Sonic [and saying], ‘We got to go out. We haven’t done enough yet. We can do more. We can just do one more sortie, there’s one more jet. Let’s just take it and go,’” Coffey said. “And she’s like, ‘Yeah, we got to go.’”

To make that happen, though, they needed a crew chief and maintainers to volunteer to leave the bunker.

“One of them stood up, Senior Airman Freer, and said, ‘Yeah, I’m a crew chief,’” Coffey recalled. ‘You want to go out there right now and launch this ship?’ [He said] ‘Absolutely,’ so [the] three of us, left the bunker. A few other folks joined us, and Sonic and I got in, started cranking. He stayed plugged in with us. When we cleared him off, he’s like, ‘Nope, until you taxi, I’m going to be right here. My job’s to get you out.’ So he chose, over and over again, with all that stuff going on, to stay out there.’”

There was a small gap in the air defense by the time Coffey and Hester were ready for takeoff, giving them an opening to go. Meanwhile, the second patrol got the order from the squadron commander: launch to survive. With missiles and debris raining down around the base, the sky was now the safest place for the fighters to be.

“The problem is, we can’t take off until we have an arming crew … pull the arming handles, the pins and make it so that we can effectively use our aircraft and weapons systems,” said Cowan.

On the flight line, Staff Sgt. Kendra Wertsbaugh and her team were responsible for a final inspection and arming munitions just before takeoff. They had watched the maintenance crew pull off the speedy combat turn just as the Alarm Red had started. Now, they were in a van, preparing to head to the bunker.

“We had two more aircraft that were not ready to be launched, but they were at chocks, waiting to taxi to be launched. So I said, you know, we have to turn around,” Wertsbaugh said. “We have these last two aircraft, who knows how long this Alarm Red is going to last? So if we do this now, it’ll be done, and after that we can get inside.”

While the aircraft taking off would be safer in the air, the ground crews would have no such luck. But Wertsbaugh was not deterred.

“Nobody else is going to do this,” she said. “I was assigned to this part. I need to stick with it.”

Staff Sgt. Ethan Tarver had helped resolve issues on jets before the alarm sounded, then he and other maintainers directed others to go to the bunkers while they stayed on the flight line to get the final jets off.

“We know how to do it in that moment. There’s so much going on, there’s so much process. There’s no room for emotion,” he said.

In their cockpits, Cowan, Sheerin, Tesch, and Diamond watched as “a team of like 10 people swarm our jets,” Cowan said.

“I don’t even know if they were the arming crews. People would run up to the jet to arm us up and then continue running to the bunker,” Tesch said.

A dozen Airmen were decorated for their actions that night, including Master Sgt. Timothy Adams, who was awarded a Bronze Star Medal for overseeing the maintainers under fire and remaining on the flight line.

Ready to go, the jets taxied for takeoff—and then stared down a runway with active air defense going off on both sides.

“The takeoff corridor that we had was out of the way of the battery firing,” Cowan said. “We took off, and I wanted to become invisible, because we still had other base defenses, and we have the other bases in the area that have their own defense zones we needed to avoid.”

Behind Cowan and Diamond, Sheerin and Tesch saw the jet’s afterburner go out at around 3,000 feet. In the darkness, with lights and explosions all around, they couldn’t tell if their flight lead had made it.

“I was convinced they had been shot down from our own air defense or hit something on the way up,” Tesch said. “So that, for me, was probably the scariest moment of, ‘Hey, it’s our turn to go. They just got hit. Now we have to follow them through that cluster of debris and flaming chunks of metal.’”

Sheerin kept the jet low over the runway, knowing debris wasn’t falling directly on it and the air defense was positioned to fire parallel to the runway, rather than across it.

“It felt kind of like a drag race,” Sheerin said. “So you are racing the air defense basically. [Tesch] talked about the Fourth of July lights—you’re chasing these fireworks and racing them down the runway. And then once we had enough airspeed, and we were past the edge of the runway, just pitching the nose up pretty, pretty high, trying to get away from the ground as fast as possible.”

In the air, Eddins and Benner returned to base after handing things over to the second alert jets. As they drew near, they saw chaos.

“When you’re under night vision goggles, you can see probably the greatest firework show you’ve ever seen, and lots of stuff raining down from who knows where, but it’s hard to tell if that’s 100 miles away or 10 miles away or if that’s directly above me,” Benner said.

At the operations desk, Wicks and others had decided to stay at their posts as the primary focal communications point for all the jets even as the alarm went off. Now, they needed to decide whether or not they should have Eddins and Benner land with the Alarm Red still in effect.

“We decided that having them divert and land somewhere else was not the best course of action,” Wicks said. “I mean, the base hadn’t actively been hit, so we’re like, if we determined that having them go somewhere else, that absolutely takes them out of the fight, whereas if we can get them down here, we might still be able to put them through the ICTs and get it back airborne. And in all likelihood, our base was still the safest place for them. So just stay airborne as long as you can, and land once you don’t have fuel to stay airborne anymore.”

With hung ordnance and low fuel, Eddins and Benner decided to land. After holding off for a moment to let the jets on the ground take off, they landed on the base’s backup runway.

“At that point, I was just focused on landing,” Eddins said. “I know that runway was not the best. About 1,000 feet down that runway is actually a little bump. So when you land and you hit that bump, it actually brings you up airborne again. You have to bring it back down with the crosswinds. It was definitely not my greatest landing.”

But they made it. On the ground, jets with hung ordnance had to be carefully positioned on the flight line so as to not be too close together. But the danger to the base was starting to fade.

At the ops desk, Wicks got the word from the Combined Air Operations Center: Stop launching jets. “Save it for tomorrow, because we don’t know what’s going to happen tomorrow,” they told him.

Yet high above, Coffey, Hester, Cowan, Diamond, Sheerin, and Tesch now confronted airspace that was still very much active. Iranian drones and missiles were still coming, and F-15 and F-16 fighters, tankers, and command and control aircraft were coordinating, as were aircraft from coalition partners and Israeli interceptors.

“The totality of the situation was, ‘Oh sh–,’” Cowan mouthed.

The swirl of missiles, interceptors, and debris flying lit up the night sky like the Northern Lights, another Airman recalled.

Like their first sortie, Coffey and Hester quickly got to work taking out threats and expended all their missiles; again, one failed to fire. As a last resort, they fired their F-15E’s 20 mm gun, but with limited effect.

As airborne mission commanders, however, they still had work to do.

“We need to coordinate the other fighters. We need to coordinate for our partners, so that they know where the threat is,” Coffey said. “And at that point, instead of trying to do subsequent gun attempts, we bring fighters back … we reset where the fight is going on, and we start handing off threats.”

Meanwhile, Cowan, Diamond, Sheerin, and Tesch entered the fight for the first time.

“We’re just all over the place, hunting down the tracks that other jets picked up and where they saw the drones and cruise missiles,” Tesch said.

The attack started to peter out. But then the crews got word from Coffey and Hester that a few “straggler” drones were 300 or so miles away. Snapping in that direction, the F-15Es raced to intercept them as they approached a city.

“Obviously that makes the hairs on the back of your neck stand up,” said Sheerin. “If you’re out in the middle of the desert, that’s fine. If something misses, something goes wrong, the worst that happens is … a random crater that could have been from an asteroid pops up somewhere in the desert.

“But as soon as you start throwing in completely innocent people who have nothing to do with this conflict, and now you have explosives flying over them, and heavily laden supersonic fighter jets flying very low altitude over them, that complicates the equation quite a bit,” Sheerin said.

Cowan and Diamond were the flight leads, but Sheerin and Tesch were in a better position to take the first shot.

“We’ve set up the intercept, and I’m waiting for him to shoot,” said Cowan. “I query him once, I query him twice, and then all of a sudden, I look up and this missile just flies off his jet and explodes in the center of my field of view.”

Despite their exhilaration, they decided against trying for a second intercept—the risk too great given the chance of civilian harm. Instead, they passed custody of the target off to coalition fighters further back.

USAFE commander Hecker praised that decision. Amid the excitement and adrenaline of aerial combat, the restraint the crews showed stood out in its own way.

After that, most U.S. fighters returned to base, while Cowan, Diamond, Sheerin, and Tesch still had to fly for several hours more. In the wake of adrenaline-infused takeoffs and dramatic shootdowns, quiet now descended as the sun rose in the east.

Looking out, the Airmen saw dozens, if not hundreds, of trails of smoke from missiles and interceptors winding through the sky.

“Like a ball of yarn,” Sheerin said.

“Like a bird’s nest,” Tesch said.

“It was one of the most incredible things I’ve ever seen,” Cowan said. “Because the sun is shining through all these missile smoke trails, it looks like a bowl of spaghetti in the sky.”

For the next several hours, the last two F-15Es patrolled the airspace as the impact of what had just happened sank in.

Coffey and Hester, returning to base, also took stock.

“We can see the Iron Dome [Israeli air defense system] going off in the distance. We can see base defense fires from all the bases around us going off. And there is a long period of about 20 minutes where we just talked about, ‘Did we do enough?’” Coffey said.

Aviators and maintainers turned on the news and got their answer: 99 percent of all drones and missiles had been intercepted, and the few that got through caused minimal damage and no fatalities. What some have called the biggest drone attack in history had been thoroughly thwarted.

“After everything was down, and all the hung missiles were put up, and we had already rearmed and got ready to go for a second round, then we had time to breathe and start processing what actually happened,” said Staff Sgt. Ethan Tarver.

The entire squadron, Coffey said, breathed a collective sigh of relief. And in the days and weeks to follow, they were able to appreciate just how much they had done, said Wertsbaugh.

“What we did was very important, saved many lives, and also showed that times are changing, and with unmanned aerial devices [threatening allies], we are prepared to just defend against anything,” Wertsbaugh said.

At Lakenheath six months later, Airmen from the 494th received awards from the Air and Space Achievement Medal to the Distinguished Flying Cross and Bronze Star. Hester became the first woman in the Air Force to receive the Silver Star.

And if, as Hecker said during the ceremony and Air Force leaders have often repeated as of late, the nature of warfare is changing, then members of the 494th can look back on that night in the Middle East as a key moment.

“I’m too young, too inexperienced even now to be able to tell you where warfare will go in the future. That’s not my purview,” said Sheerin. “But with how things continue to change, I know from the lessons learned in this as a squadron … as a fighter community specifically, I think we’re moving in a good direction, and I think we will be able to continue to assess and improve specifically with the lessons learned from the 13th of April.”

KC-135 Crews Earn DFCs

Two dozen KC-135 crew members were awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) for helping refuel the fighters that shot down 80 drones and missiles Iran fired at Israel on April 13:

11 Airmen from the Tennessee Air National Guard’s

134th Air Refueling Wing

7 Airmen from McConnell Air Force Base, Kan.

6 Airmen from MacDilll Air Force Base, Fla.

The DFC recognizes acts of heroism or extraordinary achievement in the air and is the military’s fourth-highest award for heroism, separate from distinguished service medals.

The tanker crews had to fly into that hectic airspace aboard aging KC-135s that lack the onboard defensive systems and advanced situational awareness tools of their fighter colleagues. They relied on each other and their partners across the airspace to “paint the battlefield picture” and deconflict, Tennessee pilot Maj. Cody Gaby explained.

Tanker crews rarely face the kind of challenges that merit such a high-level award. The criteria for the DFC states that “both heroism and achievement must be entirely distinctive, involving operations that are not routine. This award is not awarded for sustained operational activities and flights.”

—David Roza

How Guardians Sparked Fight

to Defeat Iran’s Missiles

When the Space Force detects a missile launch across the globe, alarms sound and Guardians scramble to calculate trajectories, identify impact areas, and alert troops and allies who may be in harm’s way.

When Iran launched some 300 ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and one-way attack drones toward Israel April 13, the alarms ringing through the operations center were unlike anything the Guardians of Space Delta 5 had heard before.

One missile is “ding, ding, ding, and then it tells you what’s going on, ” said Delta’s division chief for current operations. “But it’s the kind of thing that once you’ve heard it 300 times, it’ll give you nightmares for the rest of your life. It just keeps playing.”

With each “ding” Guardians began calculations, validated the data, and passed information along. Crews of a half-dozen or so Guardians worked together on each track—and with so many, they had to work fast.

“It gets loud, but you know who you’re listening for,” said a sergeant with the 2nd Space Warning Squadron. “So we have two crew chiefs … and then we have two junior enlisted who are like the data processors, and so they’re communicating to us what they’re seeing, and then the crew chiefs are shouting out … ‘I agree with that, we’re good to go.’ And then we have one person bouncing around between the crew chiefs, making sure that everyone’s on the same page.”

Thousands of miles away, U.S., Israeli, and allied interceptors and aircraft took their inputs and put them to use, intercepting most of the incoming missiles and drones with minimal casualties and damage.

While the military response was widely reported at the time, the Space Force’s role in that defense remained shrouded in secrecy—until now. Declassifying enough of the mission for this article took senior-level intervention. Air & Space Forces Magazine spoke exclusively with Guardians who took part in the response, gaining insight into their little-understood alert mission. Some Guardians’ names and details are withheld here for security and classification reasons.

“The scale of missile attacks we have been seeing over the past couple of years is rapidly changing,” Lt. Gen. Douglas A. Schiess, commander of Space Forces-Space, said in an October statement. “We are no longer experiencing missile defense as a singular engagement but need to be prepared to provide tracking and warning of multiple missiles being shot simultaneously, as was made evident during Iran’s recent missile strike. Our Guardians, joint and coalition operators have demonstrated their expertise in this, and are able to send missile warning notifications in a matter of minutes to help protect our allies and partners in times of crisis.”

Space-based missile warning dates back to the Defense Support Program (DSP) in the 1970s, but capabilities continue to advance as the Space Force expands its capability with new satellites in all orbits.

Space Operations Command’s Mission Delta 4 uses DSP and Space-Based Infrared System satellites for missile warning, along with the ground-based Upgraded Early Warning Radar and the Long-Range Discrimination Radar. With crews scattered across the country and overseas, in the United Kingdom and Greenland, the Delta combines the feeds from those systems to identify and track threats.

Delta 4 operates 24/7/365 to ensure no missile launch ever catches the U.S. by surprise. Yet tedious as such a constant watch might seem, Guardians never relax, said a first lieutenant with the 11th Space Warning Squadron.

“You’d think that would be the case, where you’re worried about people losing their focus and whatnot,” said the lieutenant, who was part of the crew that responded to the October attack. “But I think we realize as a unit how big of an impact we have and how important we are to the mission, that in a way, it’s hard to lose focus.”

Missile launches are most typically singular events. But since January 2020, when Iran launched more than a dozen ballistic missiles at U.S. forces at Al Asad Air Base in Iraq, the Space Force has faced increasing numbers of missile traces at once.

At the time of the April 13 attack, it was “unprecedented as far as the volume and scope and time constraints,” Schmitt said—some 30 cruise missiles and 120 ballistic missiles, in addition to 170 drones.

On the floor, operators knew something was coming. Iran had promised retaliation after an Israeli airstrike in Syria, but its timing was not clear.

“It kind of came on gradually,” said the sergeant from the 2nd SWS. “We saw what was happening from the first launch. It was just like, ‘All right, focus up everyone! Let’s get it done!’ And then, as it just kept growing and growing, we just had to really revert back to the basics of our training and just really focus in.”

The duty crew that day was newly formed for a new force-generation cycle, so they were still getting to know each other.

“There’s a lot more communication when you’re trying to find that chemistry, you’re pretty much saying every single thing you’re doing,” the sergeant said. “On a crew that I work with for a year, I already know, without them saying, what my counterpart is doing. Whereas now, with the new crew, it’s like, I’m going to voice what I would normally do, they’ll voice what they normally do, and then we can kind of get into the flow of things.”

Time raced by. The process for tracking missiles is the same no matter what the volume of incoming looks like, said Mission Delta 4’s senior enlisted leader, Chief Master Sgt. Kyle Mullen.

“They will be monitoring, and then they will get alerted with an audible [sound] that something is happening or that something looks like a missile,” Mullen said. “And so what they’ll do is, … check its trajectory, check to see what profile it’s building out. We have a two-person verification [team] so you’ve got somebody right there beside them, another experienced operator who’s like, ‘Yes, I see it. It’s going to this area.’”

Then they notify the Combined Space Operations Center.

“The first thing we’re looking at is, which sites are in the risk area,” said the Delta 5 division chief, a major. “Next thing is, do we have any personnel, naval vessels, anything else out there we need to do as a secondary, immediate communication. And then the third piece is looking at the overall status of data coming out.”

Because the CSpOC is responsible for notifying U.S. and allied assets if they are in harm’s way, phone calls and notifications flew—“sheer chaos,” the major recalled. While the missiles were meant for Israel, U.S. assets in the region were in their path, so troops were scrambling to safety.

The danger wasn’t a direct threat to the Guardians, but to air and ground crew half-way around the world. The Guardians just knew the quality and speed of their warnings were making a difference.

“As you’ve worked it more and more, the concern [is] for what’s happening for people in the region, right?” the Delta 5 major said. “Because every missile has the potential for a loss of life.”

But operators thousands of miles away were picking up their cues, heading into the fight, and in the end, 98 percent of the weapons hurled toward Israel were shot down, intercepted, or landed without effect.

Back in their operations centers, the crews came off their shifts and started to realize the enormity of what they’d just experienced. That night and in the days following, they saw news reports about the attacks, and took satisfaction in the fact that there were no U.S. casualties and minimal damage in Israel.

“Sometimes you don’t see the effect that you have when you’re sitting in the chair, but seeing the impact afterward is surreal,” said the 2nd SWS sergeant. “I had a friend that was deployed in the CENTCOM [area of responsibility] at the time, and just talking to him the next day, ‘You good? Everything good? How are you doing?’ Stuff like that.”

Meanwhile, Space Force leaders were already drawing lessons from the fight. Looking at Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, officials knew missile barrages were becoming more and more common. With their newfound firsthand experience, Guardians got to work training for what commander of Mission Delta 4., Col. Ernest “Bobby” Schmitt, called the “new normal.”

‘Even Better’: October 2024

By October 2024, Space Force leaders had a better understanding of what future attacks could look like. Guardians had responded well in April, yet there was clearly room for improvement.

“Every second counts when you’re trying to avoid getting hit by missiles,” said Schmitt.

So when Iran attacked again on Oct. 1, sending a new barrage of 200 ballistic missiles hurtling toward Israel in the largest ballistic missile attack in history, USSF was ready.

“First time, we did well; second time, we did even better,” said one major, the division chief for current operations at Space Delta 5. “We had a far better data fidelity rate. We had a lot better warning times. We just—we worked better.”

“There are always things to improve,” said a Space Force First lieutenant, a crew commander with the 11th Space Warning Squadron. “The whole point is to always become better as a unit, become better as a team. Some things that we did exceptionally well: communication, and everyone understanding the roles and responsibilities. I can’t really point to anything that went poorly. … I mean, we killed it. We killed it.”

A comprehensive look at the April attack and a push to better prepare Guardians for more and more of these large-scale attacks got the Space Force to that point, Schmitt said. “Between April and October, in our internal discussions, as we went through the debrief process and internal things we can improve, I think it became very clear that [large-scale multimissile attacks] was what we could expect going forward—that kind of volume and timing.”

Guardians needed to adjust to working through such scenarios—and the April attack had provided a blueprint, said a sergeant who was on the ops floor with the 2nd Space Warning Squadron during the first attack.

“What Iran showed in the aggression in April really showed how they operate,” he said. “So we were able to take that data and build new training based around [those insights].”

The unit’s mission planning cell defined tactics, techniques, and procedures to handle the mass of missiles and “to do it more efficiently.”

Meanwhile, the Space Force was transitioning to a new force generation rotation schedule. Dubbed SPAFORGEN, the rotation model was developed to ensure Guardians could rotate through periods of dedicated day-to-day ops and other periods dedicated to training—specifically ensuring that units aren’t doing both at the same time.

“The squadrons use the training tools they have to go build simulations … and to be able to put the crews through it,” Schmitt said. “The crews go in, they mission plan, they get the intelligence that is part of the scenario. They run through these types of scenarios. … SPAFORGEN has given us an opportunity that we never had before.”

The 11th Space Warning Squadron was also able to pick up tips from the 2nd Space Warning Squadron, Guardians said, which introduced new tactics and techniques that operators put to use on the floor in October.

“That feeling of preparedness is a result of hard work and training day in and day out,” the first lieutenant said. “So when I looked around on Oct. 1 and I looked at my team as their crew commander—the leader of the team—I knew that we were ready. A lot of waiting, a little bit anxious. But it was good. It was good. It’s not like we were nervous because something bad was going to happen.”

At the Combined Space Operations Center, where Guardians receive data from missile warning and feed it to troops in danger, Delta 5 was likewise ready, said the major.

During training, both the missile warning and command and control elements identified areas for improvement. Schmitt declined to elaborate, but he and senior enlisted leader Chief Master Sgt. Kyle Mullen noted that the team found ways to “surge” coverage without requiring additional personnel.

“The whole name of the game for us is readiness,” said Mullen. “We have a laser focus on how ready should we be, need to be, and exercise that on a routine basis. So … if it’s a slow day, they are still practicing, refining, debriefing, talking about upcoming things, what could be happening. Intel-threat-informed, warfighting-

type decisions need to be made in case that day comes again.”

At the CSpOC, faster communication was the key: “Basically cutting out anything that wasn’t necessary for that sort of situation,” the major said. “Anyone who’s worked these kinds of operations knows it’s usually very script driven. You’re trying to follow the procedure, make sure you don’t miss anything. But when a barrage happens, you don’t have time to process the script as it is. We came up with some truncated reporting that got just that critical information to exactly the right people.”

Smoothing information flow was also crucial. At the CSpOC, “data is a choke point,” the major said. “We essentially got rid of a couple of those choke points so that we could have far more events recorded, not only by our people, but also by our data systems that are reviewing everything.”

Software updates to enhance data presentation also helped. Software updates can take years between refreshes, but Delta 4 and others have become “Integrated Mission Deltas,” which combine sustainment and intelligence, shortening those cycles. Delta 4 had not made that switch by October, but Schmitt praised Space Systems Command for “bending over backward” to get software improvements fielded in the wake of the April events.

When the second barrage came in October, the new training, processes, and software were ready, fueling a quiet confidence on the ops floor for the 11th Space Warning Squadron.

“You could have heard a needle drop on the ops floor,” the first lieutenant said. “Just the focus, a focus like you’ve never seen before.”

Unlike the first attack, the October barrage consisted almost entirely of ballistic missiles, launched from multiple locations. The result, however, was mostly the same—limited damage and no U.S. casualties. And Schmitt noted that the Space Force’s role went beyond just warning people to get out of the way.

“It’s not just about duck and cover. It’s about defenses as well, and the more time they have to respond, the more effective they’re going to be,” he said. The Space Force transmits its data to ops centers around the globe and in theater, and those centers can task forces to take out the threat.

In October, the U.S. Navy fired off a dozen interceptors from ships in the Mediterranean Sea, while Israel and Jordan intercepted others. According to media reports, only one person was killed by the strikes, and most of the missiles were intercepted.

“As soon as it ended, I just remember sitting there and just being proud,” the first lieutenant said. “It’s hard to describe, but I was proud, because you and a team of people that you’ve been working with and training with are putting in countless hours for something like this to happen. You hope it never does, but when it does, it feels like your hard work paid off.”

A few weeks later, Delta 4 was recognized for their efforts by the Air Force Historical Foundation, which selected Delta 4 for the Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle Award, given to a unit for accomplishing its mission with aplomb while under difficult and hazardous conditions in multiple conflicts.

The Doolittle Award had gone exclusively to Air Force commands until then. Delta 4, whose response was so critical to fending off the October attack, is the first Space Force unit ever to win the award.