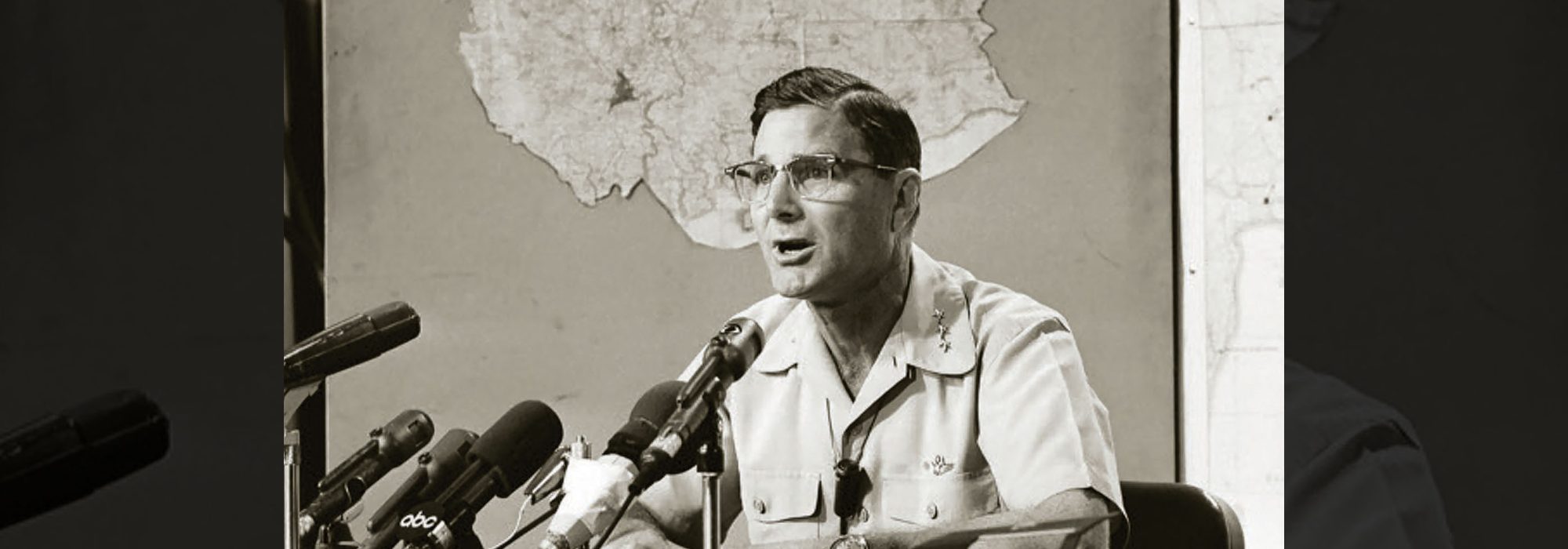

Mr. Tactical Airpower.

William Momyer, known as “Spike,” was an outstanding tactician who was instrumental in developing and implementing air doctrine throughout his career. After graduating from the University of Washington in 1937, he became an aviation cadet and won his wings. In 1942, during World War II, he deployed as a group commander for the invasion of North Africa, where he proved himself an Ace fighter pilot, earning eight victories, the Distinguished Service Cross, and three Silver Stars for operations in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy.

He made a name for himself as both a pilot and staff officer who studied tactical air operations closely. He objected, for example, to the then-prevalent practice of tying aircraft to ground units or having them orbiting overhead to provide support. To Momyer, this was counterproductive. He pushed instead to aggressively gain air superiority by destroying the Luftwaffe, either in the air or on the ground. His ideas soon became accepted as basic air doctrine: Achieve air superiority first; then conduct air interdiction of enemy supply lines; and then fly close air support. To him, such a priority would best achieve the primary goal of saving the lives of Soldiers on the ground.

After World War II Momyer served as a fighter commander at all levels, including a group in Korea. He attended the Air War College, then remained on the faculty, following that up as a student at National War College. Momyer was also a planner at Tactical Air Command headquarters at Langley Air Force Base in Virginia. He was the expert on air/ground cooperation.

As a lieutenant general in 1966 he went to Vietnam as the 7th AF commander in Saigon—he would soon get a fourth star. Given the ubiquitous role played by airpower, he pushed the commander, Gen. William Westmoreland, to name Momyer as his deputy. Westmoreland refused, stating that this was a ground war and should be commanded by ground officers. Momyer was instead to remain a “Deputy for Air.” In this role, he was to provide “timely advice and recommendations” and seek to “synchronize” air operations. It was a meaningless title that possessed no staff and gave Momyer no added authority over air operations in South Vietnam, much less control over the course of the war. Essentially, Momyer was a high-ranking tactician.

Momyer was a brilliant thinker, a trait that tended to make him less tolerant of those who could not keep up with him. His memoirs, “Airpower in Three Wars” (Government Printing Office, 1978), look back on his career and draw a number of cogent lessons—some of which, unfortunately, were not learned.

He stressed continuously the importance of gaining air superiority, and in Vietnam he was particularly disgusted with the rules of engagement (ROE) that prohibited attacks on enemy airfields and surface-to-air missile sites unless they were “threatening”—i.e., they shot and missed—and the inability to strike most of the lucrative targets in the North that were inside prohibited zones around Hanoi and Haiphong, as well as the buffer zone along the Chinese border. These zones were established in Washington and generally only lifted by the approval of President Lyndon B. Johnson.

To Momyer, and indeed, most U.S. pilots, these ROE were ridiculous, as well as dangerous, because they made it impossible for the U.S. to achieve air superiority by taking down North Vietnamese air defenses, which could have been done in 1964. Instead, such limitations on airpower meant U.S. losses were heavy and the air war became a war of attrition, every bit as demoralizing and bloody as the ground war in the South.

In fact, Momyer argued that the entire air strategy formulated in Washington was fatally flawed. It was never made clear what exactly the President and his civilian advisers wanted airpower to accomplish. When pushed for goals, the results were vague: Disrupt the flow of supplies to South Vietnam; raise the morale of the South Vietnamese; and make North Vietnamese leaders more amenable to negotiation. Only the first objective had a military flavor; the others were psychological, and such psychological goals are notoriously difficult to achieve with measurable results.

Momyer left Vietnam in 1968 just as Rolling Thunder was grinding to a halt. He returned to the States and took over Tactical Air Command. From that position he worked for the next four years to provide ever more effective weapons and tactics to be used in Vietnam. He remained “Mr. Tactical Airpower,” and was instrumental in pushing for the A-10 ground support aircraft.

Momyer retired in 1973 and published the memoirs noted above in 1978. He died in 2014 at age 95. An outstanding biography is by then-Col. Case Cunningham, William W. Momyer: A Biography of an Airpower Mind, which was a 2013 Ph.D. dissertation at the School of Advanced Air and Space Studies and can be accessed on line.