When the first batch of Air Force warrant officers in 66 years graduates from their new training school at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala. on Dec. 6, it will mark not only a new era for the Air Force, but also a major bureaucratic achievement as career field managers, personnel gurus, and other experts sweated behind the scenes to stand up the new program in less than a year.

For an organization as large as the Air Force, big changes often take a while. But when Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall announced the return of warrant officers in February, he gave planners a tight deadline: graduate the first batch by the end of the year. Lt. Col. Justin Ellsworth, career field manager for cyberspace operations officers, clocked 296 days between the official announcement in February and the graduation on Dec. 6.

“We found out about it a few weeks prior to SecAF’s announcement, and from that point forward it’s been all hands on deck,” he said.

Enlisted and commissioned Airmen are developed to eventually serve leadership functions, but that takes time and focus away from hands-on skills, which is particularly disruptive in fast-moving career fields such as cybersecurity and information technology. Warrant officers cover that gap and serve as dedicated technical experts, said assistant secretary of the Air Force for manpower and reserve affairs Alex Wagner.

“With perishable skills, like cyber, like IT, where the technology is moving so rapidly, folks who are experts in that can’t afford to be sent off to a leadership course for eight or nine months,” Wagner said in April.

Bringing back warrant officers now is particularly crucial as the service tries to stay ahead of rivals such as China and Russia, said Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin.

“We are in a competition for talent, and we understand that technical talent is going to be so critical to our success as an Air Force in the future,” Allvin said in February.

But realizing that vision in such a short time was a challenge. Each rank in the Air Force has policies and systems for pay and benefits, retirement and separation, service commitments, constructive service credits, and other factors of day-to-day military life.

One of the planners charged with figuring out how those policies and systems would work for warrant officers was Lt. Col. Marjorie Barnum, chief of the retirement and separations branch within the Air Force Directorate of Manpower, Personnel, and Services, or A1 for short.

“There was a lot of behind the scenes work to make sure that the pay and personnel systems were ready to incorporate” the new ranks, Barnum explained. “It’s definitely still a work in progress, but the right thing to do by the new warrant officers is to have that done before they finish warrant officer school.”

Beyond that, planners also had to figure out how to convene boards for evaluating future warrant officers, how to strike the right force balance, and how to reintroduce the ranks to an Air Force that had not seen warrant officers since the 1980s.

Col. Andrew Feth, who represents the Air Force Chief Information Officer on the warrant officer project, likened it to a famous scene in the film “Apollo 13” where NASA engineers dump spare parts on a table to figure out how the imperiled astronauts could save their spacecraft with the gear they had on hand.

“We were all the parts on the table,” Feth explained. “We all had our own skills and knowledge within our own areas, as you see in a lot of large bureaucratic organizations where everybody has a role. We had to figure out ‘how am I going to get this done with all these different stovepipes?’”

Just 10 days after the initial announcement, officials at Air Force headquarters met with representatives from the other services to learn the institutional roles of their warrant officer programs. Then they met with Air Force IT and cyber experts to figure what functional roles warrant officers ought to fill based on that guidance.

Eventually, the Air Force decided WOs would play three roles: professional warfighters, technical integrators, and trusted advisors. Meanwhile, Air University stood up a Warrant Officer Training School in June, to be staffed by Airmen who graduated from the Army warrant officer instructor course in July.

Back at Air Force headquarters, the cross-functional team stepped outside their usual lanes to hammer out the policy details.

“I learned a lot more about A1 personnel policy than I’ll ever need to know,” Ellsworth said.

Barnum said another key factor was support from the highest levels of the service, including multiple Air Force headquarters directorates, the Air Force Personnel Center, and Air Education and Training Command. Leaders from all corners agreed on the importance of having warrant officers and shared a vision for its success.

“That gave us the engagement down into the functional levels,” Barnum said. “If it’s a priority for your boss, it’s a priority for you.”

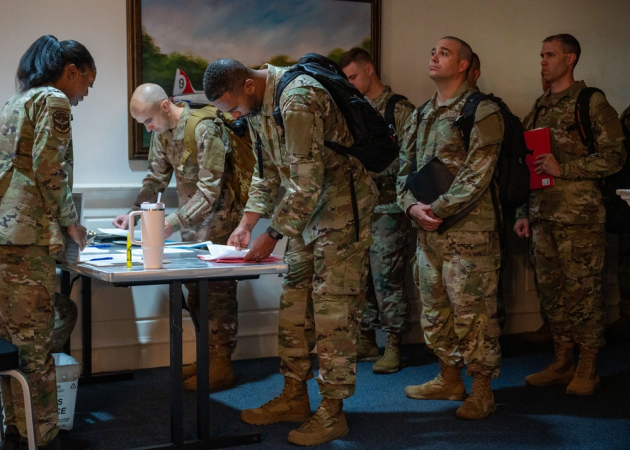

It helped that the rank-and-file were also fans of the effort. Nearly 500 Airmen applied for just 60 slots when applications opened in April, two months after the program was announced. Of those, 433 applications were deemed eligible, but the caliber of the applicants was so high that officials decided to bump the first cohort to 78 slots. As a career field manager, Ellsworth felt that enthusiasm in person during visits with Airmen.

“They were so pumped to see this come back again, we already have folks asking when the next board is going to be,” he said. “Just having that really helped make this a success.”

At the end of the day, it took elbow grease; when asked how many hours they spent working on the warrant officer project every week, the team members laughed.

“Let’s say we’re happy that the government doesn’t pay overtime,” one of them said. “Otherwise we’d have resource problems.”

The work isn’t over: outstanding questions include modeling the right mix of skills and grades to retain as the number of warrant officers grows, and what professional military education will look like for the warrant officer corps. Further down the road, the Air Force is still working out its “street-to-seat” program, where qualified civilians go directly into the warrant officer corps.

The Army has a similar program for its cyber warrant officers, and the fiscal year 2025 defense spending bill includes language that would remove a one-year service requirement so that the Air Force can do the same.

“The idea is to fill specific roles where we don’t have a strong bench right now within the military,” Feth said. “We want to make sure we get the right people in the right positions so that we can get after the great power competition gaps.”

In the meantime, officials launched a warrant officer roadshow—a series of town hall briefings and leadership meetings at bases across the Air Force to get them ready for the new ranks.

“The last regular Air Force warrant officer retired in 1980, so it’s been a minute,” said Ellsworth. “We want to make sure when the warrant officer shows up, [the base] understands here’s how you utilize him or her within your organization.”

The lieutenant colonel pointed out one last factor that helped stand up the warrant officer program so quickly: the threat of rivals such as Russia and China.

“This focus on great power competition has galvanized us as an Air Force to come together and get things done,” he said. “I’ve been in the Air Force just about 18 years and I’ve never seen us move this fast on a program.”