The Department of Defense is eyeing localized quantum sensors as a radical alternative to space-based Global Positioning System satellites in the face of increasing threats to GPS signals needed for precision navigation and timing.

In a peer conflict, notes Lt. Col. Nicholas Estep from the Defense Innovation Unit (DIU), “you really must presume a denied and degraded environment in which you cannot rely upon external PNT signals like GPS.”

That’s why DIU, the Pentagon’s acquisition outpost in Silicon Valley, is seeking commercial partners to help develop distributed, localized alternatives that don’t rely on easily jammed signals from thousands of miles above the earth’s surface.

The military depends on GPS for navigation, timing, and targeting, and industries from transportation to agriculture to banking rely on its precision for a host of purposes. But the wars in Ukraine and the Middle East have exposed how signal jamming and spoofing can deny access to signals from space, forcing users to seek alternatives.

“What are we going to do in order to maintain PNT-enabled solutions, to allow the joint force to execute its mission?” asked Estep, whose DIU portfolio includes quantum sensing, hypersonics and advanced materials.

DIU solicited industry seeking quantum sensing technology that could augment or back up GPS satellites for military applications within a couple of years. The “project will focus on demonstrating the military utility of quantum sensors to address strategic Joint Force competencies,” DIU said at the time.

Dozens of proposals poured in, Estep said: “We did get a very strong signal of interest from the community, a mixture of traditional primes, startups, and non-traditional companies.”

The solicitation was designed to encourage a variety of approaches and solutions, Estep said. “There won’t be one quantum sensor to rule them all, that that the Air Force will use, that the Navy would want to use, that the Army [would want to] … There’s no panacea—quantum or classical—to address all of the joint force PNT needs.”

Instead, he said, DIU would seek to marry the various approaches presented by industry applicants with appropriate use cases, based on the form factor and the maturity of the technology. “Some [approaches] may be better suited for aircraft. Some are better suited to support surface or subsurface vessels,” he said.

DIU is working with multiple services and other stakeholders in the Department of Defense to get these innovative solutions into warfighters’ hands as quickly as possible, Estep said, “And so we help to coordinate these different technology solutions, with what we think best correlates to service deployment mechanisms and diverse mission sets… in several different parallel [acquisition] pathways.”

The Space Force is also working on resilient space-based PNT solutions, including by spreading GPS signals out across a diversity of satellites in different orbits, as a means to make the system more robust and less susceptible to interruption. Indeed, resilient PNT was one of two capabilities identified by Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall for use under the new “Quick Start” funding authorities enabled by Congress to let the Space Force move ahead on some programs without having to wait for a full legislative review.

Quantum Sensing

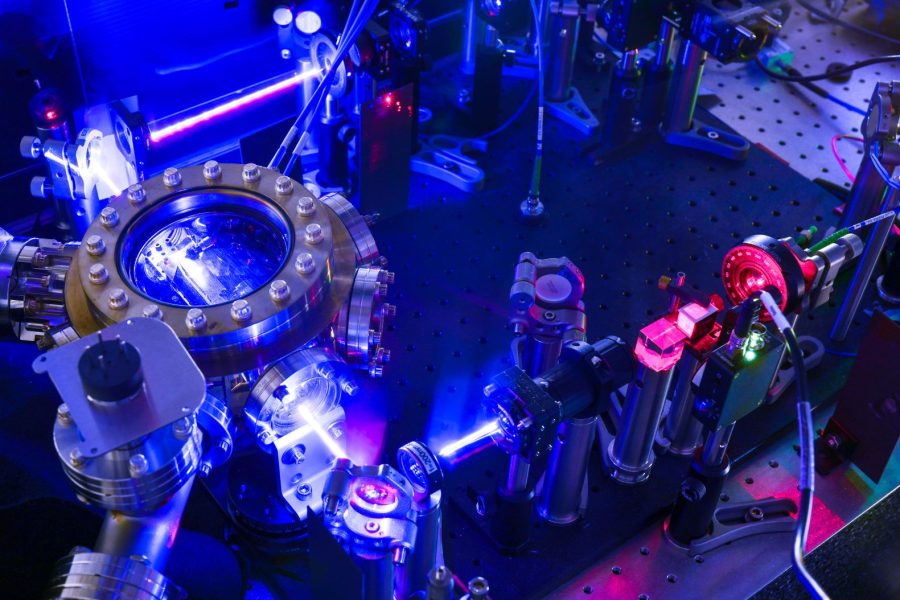

Quantum mechanics involves the extraordinary, counter-intuitive, and often confusing properties of subatomic particles first explored by Albert Einstein nearly a century ago. Recent advances in nano engineering have enabled labs for the first time to demonstrate and exploit the unique properties of quantum particles, generating renewed excitement about the technology.

Celia Merzbacher, executive director of the Quantum Economic Development Consortium (QED-C), an industry-led stakeholder forum supported by the National Institute for Standards and Technology, said that quantum sensing is among the least understood but most mature of three quantum mechanics fields—the other two are quantum computing and quantum communications.

“Quantum sensing for PNT is, to some extent, already here,” she said. The technology is the same as that used in atomic clocks, which provide precise timing based on the movements of subatomic particles.

In a September report, QED-C noted that “Quantum sensors can provide navigational information in environments where GPS signals are unavailable or unreliable.”

The report and the DIU industry offering outline three ways quantum sensing can be applicable to PNT: Measuring movement, gravity, and Earth’s magnetic field.

Each offers a way for a plane, ship, or vehicle to accurately ascertain its position, without having to rely on radio signals from faraway GPS satellites.

Merzbacher predicted that DOD’s involvement could spur a commercial market for quantum sensing PNT within five years. Without DOD, it would take longer, she said, “because these companies that are developing quantum sensors for PNT and other uses are smaller companies, and they have somewhat limited resources to invest in anything that’s beyond two or three years to market.”

This is precisely the kind of problem for which DIU was created—as a bridge to private equity. “Private capital is expensive and very hard to get,” Merzbacher said. DOD is effectively vouching for its view that a market could emerge.

“Government can really accelerate progress by stepping in and helping to defray the cost of the engineering and R&D at this stage,” she explained. “Eventually the flywheel will be spinning, and as revenues are being generated, those companies can reinvest. But if the government doesn’t step in and invest … then progress will just be much slower.”

The QED-C report identified the transition from lab to battlefield as a key hurdle. “A big challenge is integrating these new components that are really just being developed in the lab, in a controlled environment, integrating and packaging those into something that can go onto a plane or a Space Platform,” and withstand the rigors of vibration or radiation, she said.

“There’s going to be a lot of work needing to be done,” she said.

Meanwhile, China and others are investing in their own solutions, said Dana Goward, a career U.S. Coast Guard officer who is now president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, a 501(c)3 scientific and educational non-profit.

China (and U.S. allies South Korea and Saudi Arabia) already had a functioning terrestrial alternative to GPS in an Enhanced Long-Range Navigation (eLORAN) system, Goward said. eLoran relies on hyperbolic navigation, where a plane, ship, or vehicle can ascertain its location by correlating signals from two or more terrestrial broadcast towers.

“It’s much more accurate, much more difficult to disrupt,” than GPS or other satellite-based PNT, said Goward.

Goward called quantum sensing “exciting,” but said it could be “many years” before the technology clears all the necessary engineering and regulatory hurdles necessary for broad adoption. “How close are we to something that is viable in any commercial application?” he asked.

GPS is now taken for granted by consumers and businesses, Goward said, and there is little understanding of how fragile it is. But technologies that require materials to be maintained at extremely low temperatures or to operate at extremely precise laser frequencies are hardly ready for prime time, he said. “They’ll keep making it better and better, and perhaps someday it will get down to the common folk like you and me.”

Quantum Orienteering

The supporters of quantum sensing for PNT say it represents a step change, away from the inherently fragile beacon-signal approach of GPS or even eLoran. “The next generation of PNT technologies returns positioning to the local vehicle or individual and it says, essentially, now we want to be able to navigate using only things that we measure locally,” said Michael Biercuk, CEO of Q-CTRL, a quantum technology company.

Because the Earth’s magnetic and gravitational fields vary minutely from place to place and because those variations have already been mapped, a tool that can measure those minute variations can accurately locate the user, Biercuk explained.

“If you combine a really good map of these geophysical phenomena with a really good local sensor, you can do what we sometimes jokingly refer to as quantum orienteering,” Biercuk said, “You can take your map and your sensor and figure it out where you are.”

The extreme technical requirements of quantum sensing equipment can be mitigated by the use of software algorithms, he said.

“The laboratory performance is extraordinary, but the performance outside the lab is tremendously degraded. Anytime you put it on a moving vessel, it’s really hard to keep it operational. They’re very, very sensitive devices,” he said.

But Q-CTRL had been “able to show that when you combine, obviously very good hardware engineering with software enablement, you can actually make these tools viable in real environments,” he said.

The company is working with Airbus on safety-testing a GPS-replacement inertial motion sensor that could be installed in commercial aircraft “within two or three years,” he said.