This is the first in a two-part series based on exclusive interviews with five Airmen who helped save a patient’s life in a long-range rescue mission Oct. 9. Part 2 will publish Thursday, Nov. 21.

The bulk carrier Port Kyushu stretches the length of two football fields, but it looked like a toy against the vast, dark tablecloth of the Pacific Ocean. Peering down from the window of a C-130, Staff Sgt. Mike Scheglov offered up a simple prayer.

“I really hope that they speak Russian.”

About five hours earlier, Scheglov had been working at Moffett Field, home of the California Air National Guard’s 129th Rescue Wing. It was the morning of Oct. 9, and Airmen were preparing to pick up a patient from a ship 500 miles off the coast of San Francisco. As an aircrew flight equipment specialist, Scheglov was prepositioning their gear when his supervisor asked an unusual question.

“Did you bring your lunch today?” Scheglov recalled.

The rescuers needed a Russian speaker to communicate with the ship captain. A native speaker, Scheglov was a perfect fit. He grabbed his lunch.

The 129th Rescue Wing is one of few organizations on Earth that can rescue patients hundreds of miles offshore, thanks to its fleet of HC-130J command and control planes and HH-60G helicopters. The HC-130Js refuel the helicopters via long hoses that trail behind the wings mid-flight, where an HH-60G plugs in with a long probe sticking out the front of its fuselage.

Air refueling gives extra range to the helicopters, letting them hoist patients out of anything from a fishing boat to a cruise ship and bring them back to a hospital. But it’s a high-risk job, said Lt. Col. Christopher Nance, who commanded the Port Kyushu mission.

“There are a lot of moving parts in a helicopter,” said the HC-130J pilot. “If you’re flying over land, helicopters can find a field to put down or C-130s can find an airfield, but there are no options over water. And the further out you go, the longer it takes to get back.”

Once the aircraft reach the target vessel, they hoist down a Pararescue Jumper (PJ) to pick up the patient. A blend of commando and expert medic, PJs are trained to save lives under fire anywhere on Earth, but dangling from a helicopter over a moving vessel in the open ocean is dangerous for anyone.

“Anytime you put a human being out the back of your aircraft, that is immediately high risk,” Nance explained. “There’s just so many complexities to the mission.”

There’s also the fatigue of flying for hours at a time, often in darkness, sometimes low to the water, and usually in airtight anti-exposure suits.

The suits are designed to keep the Airmen alive if they have to bail into the frigid Pacific, but they can get pungent and uncomfortable after a 10 or 11-hour sortie, said Senior Airman Reese Williamse, a special missions aviator who works in the back of the HH-60. That’s led to a colorful nickname: “Poopy suits.”

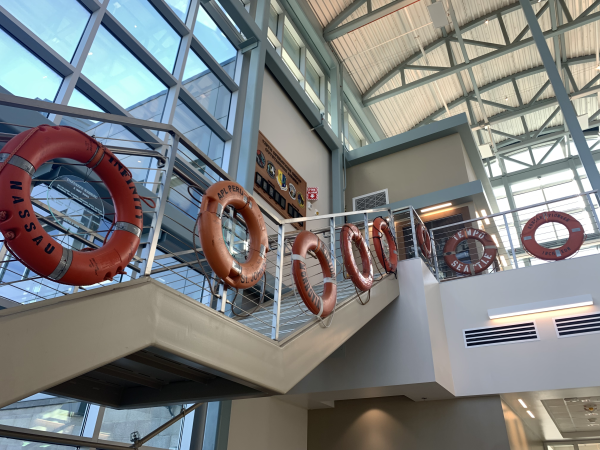

Such challenges are nothing new for the 129th RQW, which has been flying open ocean rescues since 1975. The halls of the Moffett squadron buildings are lined with orange lifebuoys given to them by the crews of the dozens of ships from which they’ve rescued patients. The Port Kyushu mission would mark the wing’s 1,165th life saved, though that number includes deployments and non-ocean rescues.

“We’ve done it so often here that, to be honest, we’re really good at it,” Nance said. “So our comfort level is quite high compared to other units that may not have accepted a mission like this because it was too high-risk.”

The Crew

The call for a rescue came in from the U.S. Coast Guard on Tuesday, Oct. 8. A middle-aged man on the Port Kyushu was having what would later be diagnosed as an urgent neurological problem. The wing asked not to print exact details out of concern for his privacy, but at the time, the patient was generally unresponsive and not accepting food or water, so his crewmates worried he would not survive the rest of the voyage.

A rescue would risk four aircraft and more than 20 lives to save one, but medical experts and wing leadership deemed the gravity of the situation outweighed the risk. There was no issue finding volunteers.

“Sometimes we get guys out of state that are like, ‘hey, I’ll fly in,’” Nance said. “You get guys who will definitely take a day off of work to come out and support one of these.”

But there was a problem: the wing needed two HC-130Js to cut down on risk and haul all the gas necessary for the long flight, but due to maintenance issues only one was ready to fly. The next closest HC-130J unit is the Active-Duty 79th Rescue Squadron at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, Ariz., which had just spent the past two weeks on the East Coast responding to Hurricanes Helene and Milton. But they answered the call, sending two C-130s just in case, while the co-located 55th Rescue Squadron sent two HH-60Ws if needed.

“When you’re dealing with long-range over water, you want to have spares,” Nance said. “It’s a testament to the joint force that one, they were willing to respond after everything they’d just gotten back from, and two, how seamlessly they integrated with us.”

At around 11 a.m. Oct. 9, the aircraft took off for the Port Kyushu, which would be about 500 miles off shore by the time they rendezvoused. Both HH-60Gs and one of the HC-130Js came from Moffett, while the other HC-130J came from Davis-Monthan.

“I wasn’t nervous or stressed because I knew all the guys in the other planes, and they’re all professionals,” Nance said. “They know what they’re doing.”

The Gear

A rescue package does not travel light. Besides the anti-exposure suits, the helicopter crews and PJs also wore orange inflatable life preservers, which sometimes called “water wings” or “Cheetos.” They also carried tiny bottles of compressed air to breathe from while escaping a sinking helicopter.

On top of that, the PJs brought IV fluids, drugs, oxygen, blood pressure cuffs, monitors, a litter, and enough other medical supplies to fill the bed of a pickup truck, all squeezed into a helicopter cabin not much bigger than a hot tub. It gets even more cramped with a patient aboard.

One of the PJs, Senior Airman Connor, whose full name was withheld for security reasons said he had “probably like a three-by-two foot space I was in for five hours.”

But there’s still room for a keepsake or two, which for some Airmen play as vital a role as their helmets and exposure suits. Nance carried a medallion his uncle gave him when he first got his flight wings—and a pencil-shaped tire pressure gauge tucked into the sleeve of his flight suit.

“When I was a brand new lieutenant, a bunch of guys talked me into buying a Harley, and they convinced me that I had to be checking the tire pressure all the time,” he said. “They were messing with me, but in 2009 I was deployed, and we almost had a midair [collision] with a Marine CH-53 [helicopter]. Our aircraft commander saved our lives, but my tire pressure gauge disappeared. After that I never flew without it.”

Flying the lead helicopter, Capt. Parker Imrie carried a challenge coin from the 3rd Battalion, 5th Marines, the unit his late brother served with in Afghanistan. In the back of the helicopter, Williamse, the SMA, carried a fish keychain his wife gave him years ago.

Into the Blue

The rescue package flew over the Pacific at about 5,000 feet, with broken clouds ahead and the marine layer, a low expanse of cloud and fog, below.

“The question is, does this marine layer go 10 miles out or 1,000 miles out,” Imrie said. “You don’t know until you fly out there.”

Early in the flight, the helicopters and C-130s tested out the refueling systems, a delicate operation where the helicopter pilot has to match the C-130’s speed and altitude while the gas flows, then back out slowly without yanking off the hose.

“If all the conditions are right, it’s not that hard. It’s just kind of a little video game: line up and plug in,” Imrie said. “But as you add weather, turbulence, fatigue, poor visibility, or having to plug on the right side of the aircraft, where you get a lot more turbulence coming off the wing, that difficulty ticks up very quickly. But it’s just a matter of practice.”

Staying calm is also key: the pilot might wiggle his or her fingers to avoid white-knuckling the stick, while the crew keeps their voices steady, almost a monotone.

“If one person starts getting tense and has an elevated voice, then everybody hears it, pilots will start gripping it tighter,” Williamse said. “Even for me in the back when I’m doing a hoist, if my voice is super fast and loud, you can feel it in the hover.”

“There’s a psychology to flying a helicopter with four people,” Imrie added.

Indeed, much like how the pilots routinely check their instruments to see how the aircraft is doing, the crew keeps up a low level of conversation during the long hours over water.

“There definitely were periods where everyone was silent for a while, which is OK,” Imrie said. “But you don’t want to let that go on for too long, because you don’t know: is this guy just silent because he doesn’t have anything to say, or did he fall asleep, or is he having a medical emergency?”

On the other helicopter, Connor the PJ enjoyed listening to the banter, but he and Tech Sgt. Sean, the more experienced PJ on board, had to save their mental strength for later.

“We just tried to relax, knowing that the next six, seven hours were going to be pretty exhausting,” Connor said.

Part 2 will publish Thursday, Nov. 21.