How the USAF can ensure it can generate combat sorties while under fire.

Front-line air bases are like any other weapon system: They are only effective if they can function under enemy fire. Air bases at forward locations in the Indo-Pacific, Europe, or other theaters must be able to fend off complex integrated air and missile strikes, rapidly reconstitute operational capabilities when damaged, and continue to generate combat effects.

The Air Force is facing many of the same air base defense challenges it did late in the Cold War. However, it is unprepared and ill-equipped to counter similar threats to its air bases today. Air base defenses have atrophied due to a lack of funding and resourcing over the past 30 years, imperiling their ability to generate the sorties and strike options that joint commanders will need to secure U.S. interests and defeat aggression.

J. Michael Dahm is a Senior Resident Fellow for Aerospace and China Studies at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.

Download the entire report at

In a future conflict, the United States must fight alongside its allies and partners as an “inside force,” operating forward against adversaries that have substantial advantages in terms of time, space, and combat mass. If adversaries can effectively suppress U.S. airpower, joint force operations will be unable to achieve operational or strategic objectives in near-peer conflict with China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) or the Russian Armed Forces. China now possesses substantial reconnaissance and long-range strike capabilities that could potentially win an air war by destroying infrastructure and aircraft on the ground without engaging in air-to-air battle.

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen. David W. Allvin underscored the need for air base defense in Senate testimony earlier this year: “We are also committed to building forward basing resilient enough to enable continued sortie generation, even while under attack.” To be an effective deterrent and to shape adversary decision-making, air base defense must do more than protect forces. It must ensure the Air Force retains the ability to project power at the forward edge of the battlespace.

Effective air base defense supports three operational objectives, especially in a large-scale, force-on-force conflict:

- Effective combat sortie generation,

- Force preservation, and

- Imposition of costs on adversary attacks.

An informed assessment of present-day threats reveals how the Air Force might achieve these objectives with cost-effective air base defense.

Many in the West are seemingly convinced of a prevalent and persistent myth: that China seeks to avoid combat—to win without fighting, in the tradition of ancient Chinese military strategist Sun Tzu. This is sometimes called a fait accompli strategy, in which an enemy force is forced to concede before hostilities commence because defeat is all but ensured. However, in historical context, Sun Tzu’s maxim is better interpreted as routing enemy soldiers before they have an opportunity to form ranks and fight back—that is, it is better to launch a preemptive strike against an unprepared enemy that brings victory without engaging in reciprocal battle. Italian air strategist Gen. Giulio Douhet made the same observation in 1921: “It is easier and more effective to destroy the enemy’s aerial power by destroying his nests and eggs on the ground than to hunt his flying birds in the air.”

Back to the Future—1985 to 2024

Today’s Air Force finds itself in a position similar to where it was at the end of the Vietnam conflict—with significant deficiencies in air base defense due to decades of underinvestment. However, by the early-1980s, the Soviet Union developed power projection and precision strike capabilities that threatened to overwhelm air base defenses in Western Europe. Despite initiatives to enhance European air defenses like the Patriot surface-to-air missile system and the Air Force’s Collocated Operating Base program, computer simulations still showed that strikes against U.S. Air Force bases in the first week of a Soviet attack would likely cut the service’s aircraft sortie generation by 40 percent and destroy up to 40 percent of its deployed aircraft on the ground.

“Salty Demo,” a multiweek airpower exercise in the spring of 1985, simulated a Soviet strike on Spangdahlem Air Base, West Germany. The simulated attacks “destroyed” aircraft, buildings, and equipment, and knocked out utilities and communications. Air Force combat engineers cratered the alternate runway with live explosives just so they could attempt repairs. As reported in this magazine in a 1988 article, the exercise was “a sobering demonstration of the synergistic chaos that ensues when everything goes wrong at the same time.”

That same year, Air Force leadership stated the priority for base defense had progressed from “urgent” to “critical.” New initiatives included hardening infrastructure and employing passive defenses such as camouflage, concealment, and deception. Damage control and rapid runway repair became priorities. In advance of those initiatives, the Air Force and Army signed a memorandum of understanding securing an Army commitment to provide ground-based air defenses for air bases. Air Force leaders began talking about “fighting the air base,” effectively operating their bases like weapon systems.

Then the Cold War ended. Over the next 30 years, regional conflicts including in Southwest Asia and the Balkans dominated military operations and planning. The U.S. Air Force enjoyed air superiority by default, operating from bases that were sanctuaries far from the battlefield. The 1984 agreement delineating Army responsibilities for providing ground-based air defense for Air Force bases expired—unnoticed—in the 1990s. Distracted by counterinsurgency operations, few military planners recognized the renewed threat to forward air bases posed by new generations of long-range precision strike weapons developed by Russia and China. While Pacific Air Forces (PACAF) advocated for building hardened shelters at Andersen Air Force base on Guam to protect B-2s and F-22s at a cost of $1.8 billion with an estimated completion date of 2008, the Air Force dropped the proposal for lack of funds.

Coming full circle, in 2023, Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall’s fifth operational imperative, Resilient Forward Basing (OI-5), repackaged the Cold War-era Air Base Operability (ABO) program as Agile Combat Employment (ACE). Both ABO and ACE disperse aircraft and spread operations across established and remote air bases rather than present a concentration of forces for adversaries to attack at main operating bases. ACE, like ABO, also necessitates more active air and missile defenses, requiring the Air Force to again seek agreement with the Army on their shared responsibility for air base defense.

Remaining an Inside Force

The U.S. Air Force must be able to generate combat sorties under hostile fire from both established and dispersed forward air bases alongside allies and partners. As stated in the Pacific Air Forces Strategy 2030, reinforcing allies and partners is a core strategic priority. Fighting forward with a coalition of like-minded nations is a cornerstone of U.S. alliance agreements and regional military strategies. Indeed, current force structure and basing simply do not allow the U.S. to “go-it-alone.” The U.S. must fight as an allied and coalition team, whether in Europe, the Middle East, or the Pacific.

More importantly, without air base defense to enable a forward-deployed inside force, the math in a near-peer adversary conflict puts the U.S. Air Force at a serious disadvantage. The current U.S. bomber force lacks the capacity to conduct the volume of strikes necessary across large countries like Russia and China. The decline in the size of the Air Force has resulted in a lack of sufficient strike-fighter aircraft and weapons to generate the sortie rates and mass needed to prevail in a large-scale conflict. This is especially true in East Asia. Relying on a daisy chain of tankers to fly fighters from Guam or Northern Australia to the East or South China Seas might generate a single long-range sortie per day for most aircraft. Strike fighters operating from forward bases along the first island chain could triple that number.

Operating within range of adversary anti-access/area denial (A2/AD) capabilities with effective air base defense capabilities serves key operational and strategic objectives. These include:

- Effective combat sortie generation. Defending forward bases and operating from those bases is the only practical way to generate required airstrikes and deliver other combat-relevant effects given the impossibility of conducting all necessary attacks with long-range, standoff capabilities.

- Force preservation: Valuable combat aircraft, support aircraft, personnel, maintenance facilities, and fuel may be difficult if impossible to replace, especially during a weeks- or months-long crisis.

- Adversary cost imposition. An adversary must expend scarce and expensive weapons in return for minimal operational effects if the Air Force and its partners execute effective air base defense. Realizing these three air base defense objectives recognizes air base defense as a core capability of a “peace-through-strength” deterrence strategy.

Complex, Integrated Threats

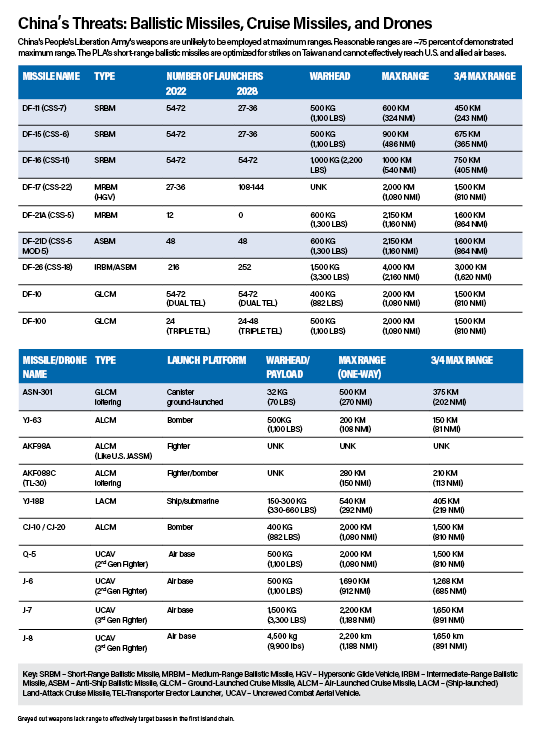

China’s PLA poses the greatest potential military threat to U.S. and allied air bases in any future conflict. The PLA’s intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities enable a large and growing arsenal of long-range precision weapons. In a large-scale conflict with China, the Air Force will face sustained, complex integrated attacks on its air bases from aircraft, ballistic missiles, cruise missiles, and drones.

China’s ISR in East Asia features layered and overlapping coverage from diverse space-based and airborne sensors generating electro-optic, infrared, and hyperspectral imagery; synthetic aperture radar imagery; and a variety of signals intelligence. Coupled with cyber and human intelligence, China can probably identify the specific location of U.S. aircraft and equipment at an air base and gather information on aircraft launch and recovery. Robust passive defenses, including camouflage, concealment, and deception measures will be critical to defeating the PLA’s ISR and long-range kill chains.

PLA attacks on U.S. air bases will attempt to overwhelm active and passive defenses. Projected attacks will include numerous low-cost cruise missiles and drones combined with more expensive ballistic missiles and hypersonic glide vehicles. Ballistic missiles, attacking from high-altitude, may maneuver in the terminal stage of flight. Hypersonic glide vehicles will ingress at high speeds and relatively low altitudes, decreasing warning times. Cruise missiles could attack at either subsonic or supersonic speeds. Additionally, propeller-driven kamikaze drones and modified remote-controlled third-generation fighters crashing into targets will add to the attack. Tracking and engaging multiple, dissimilar air and missile threats that simultaneously arrive from different directions at different altitudes and different speeds will pose a significant challenge to U.S. air defense systems.

PLA kinetic strike capabilities extend as far as 1,500 to 2,000 nautical miles from the Chinese mainland—out to Guam, the rest of the second island chain, and into the southernmost reaches of the South China Sea. Such strikes could seriously impede, if not stop, a U.S. military intervention in the region. By the late-2020s, PLA surface ships and submarines could also threaten U.S. bases in Alaska, Hawaii, California and Washington state, as well as Diego Garcia and northern Australia with land attack cruise missiles (LACM) or conventional ship-launched ballistic missiles.

The threat from the PLA’s large and growing arsenal of long-range precision strike weapons against air bases is serious, but not insurmountable. There are practical, physical limits to the number of sophisticated weapons an adversary like the PLA may launch at any given time. Defense analysts’ prevailing view is that the PRC would have “hundreds of missiles” available to attack U.S. air bases, but it will also have other targets of equal or greater value—U.S. theater air defenses; command, control, and communications; ISR capabilities; naval bases; ships; and logistics

Additionally, any growth in the PLA’s missile inventories is offset by the replacement of older missiles like the DF-11, DF-15, and DF-21 with newer, more accurate, and longer-range systems like the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle (HGV) and the intermediate-range DF-26.

The numbers of PLA ground-based missile launchers and missile reloads available further limits their offensive capabilities. The Office of the Secretary of Defense’s annual China Military Power Report suggests that key long-range DF-26 battalions may only have one reload available for its 250 launchers, about 500 missiles. Medium-range ballistic missiles like the DF-17 hypersonic glide vehicle may have two or three reloads, maybe 500 to 600 missiles total by 2028. PLA “shoot-and-scoot” tactics—rapidly relocating launchers after missile strikes—further constrain how many missiles can be launched at any one time. Furthermore, the PLA will need to use its limited inventory of weapons to target an ever-increasing list of U.S. and allied military capabilities in the region.

These limiting factors combined with the PLA’s growing target list serve to limit the number of high-end missiles available for any single strike on a U.S. air base. Dispersing U.S. and allied air forces across multiple operating locations will challenge the PLA to concentrate attacks across the 2,000 to 3,000 nautical miles of the first island chain.

Sustaining Operations Under Attack

In a recent air base defense study, the Mitchell Institute and analytic partners examined sortie generation rates during a notional Red-Blue conflict in East Asia. In the scenario, enemy Red forces conducted sustained missile strikes against U.S. and allied Blue air bases located along the first island chain. The analysis illustrated how a combination of integrated defenses allowed the Blue air force to continue operations under enemy fire. Dispersed aircraft operations across multiple locations, plus moderately effective active and passive missile defenses and supported by reconstitution capabilities such as runway repair enabled Blue fighter and air refueling tankers to quickly return to combat-relevant sortie rates while under Red attack. This assessment assumed air defenses defeated only 50 percent of Red missile strikes. ACE hub-and-spoke air base dispersal proved to have the greatest impact on countering threats because it forced Red to spread its attacks across five times as many locations.

Future assessments of air base defense and combat sortie generation should consider the increased equipment, logistics, and personnel burden inherent in executing the ACE dispersal concept. ACE under attack will require runway repair crews as well as active defense systems present at all hub-and-spoke bases. Additional, higher-fidelity modeling and assessments will help the Air Force further refine its air base defense requirements.

Operational Concept for Base Defense

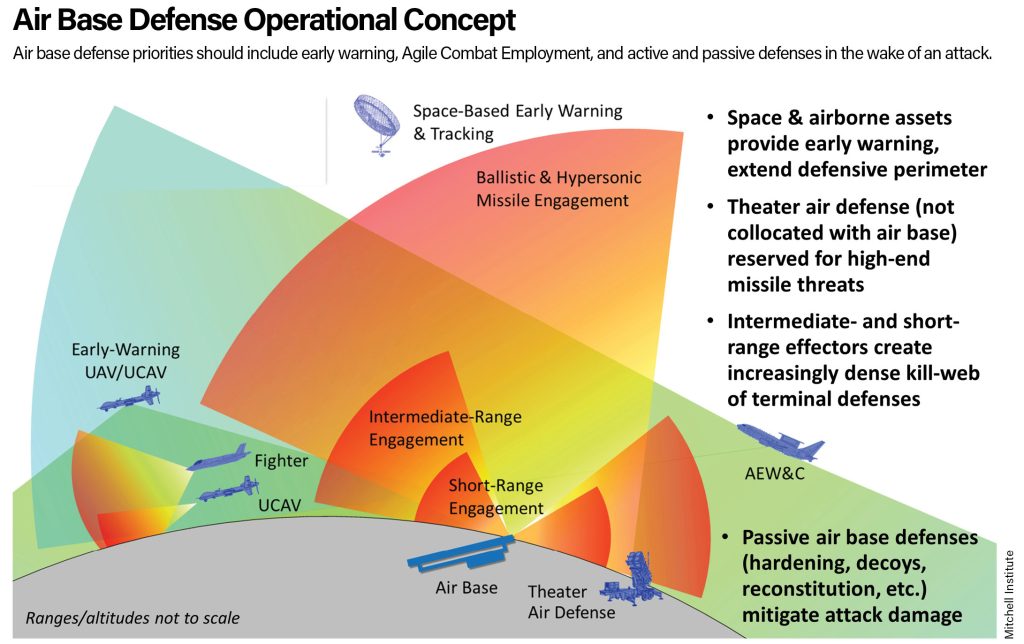

The analysis of the mix of likely threats and the proof-of-concept assessment outlined here points to three key principles and priorities in defining an operational concept for air base defense:

- Agile Combat Employment significantly improves sortie generation and regeneration during a conflict.

- A diverse, layered arsenal of active defenses including survivable, distributed active and passive sensors, as well as kinetic and non-kinetic effectors provides cost-effective protection against incoming attacks.

- Passive defenses, including hardening, camouflage, concealment, and deception are among the most cost-effective, sustainable defenses; substantial reconstitution capabilities such as rapid runway repair are essential for regenerating combat power following attack.

Aircraft dispersal across multiple air bases and alternate operating locations complicates adversary targeting with simple math while enabling the Air Force to hold targets at risk from multiple forward locations. In an East Asia conflict scenario, the U.S. Air Force may operate from air bases spread across a 2,000-to-3,000-nautical-mile front. Doing so would force an adversary like China to spread its ISR and strike capabilities across that front, imposing additional costs and potentially reducing the scale of an attack on any one base.

Practical, effective, and enduring air base defense requires an enterprise approach. There are no magic weapons that will solve all the air base defense challenges facing the Air Force. Long-range detection capabilities and a dense, close-in kill-web should complement scarce and expensive long-range air defenses such as Terminal High-Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) and Patriot surface-to-air missiles. A single Patriot costs $3.8 million; a THAAD costs $8.4 million. Such systems must be reserved for the most high-end, difficult-to-defeat adversary threats.

The Air Force and its supporting Army air defense forces require more cost-effective and combat-relevant air defense capabilities, including electronic warfare and directed-energy weapons. Airborne assets including uncrewed aircraft provide early warning of inbound threats to the air base that can also engage some low-flying threats. Ground-based air defenses should include a volume of intermediate- and short-range effectors including short-range missiles like ground-based AMRAAM and AIM-9X and cannon-based maneuvering projectiles.

Air base commanders may have to consciously allow lower-end threats to close in on an air base before engaging them with cost-effective shorter-range, systems. A long-range intercept strategy may quickly exhaust long-range interceptors against relatively low-cost enemy weapons. Allowing threats to approach air bases entails risk, but engaging them with lower-cost, short-range air defenses reduces operational risk over time, which would prove invaluable in the face of sustained attacks by a mix of high- and low-end threats.

To address those threats that will ultimately penetrate even the best active defenses, air base hardening, camouflage, concealment, and deception are important passive air defense components. A $1 million hardened aircraft shelter could last for decades and a $100,000 decoy is a bargain-priced insurance policy for a $100 million aircraft. Redundant fuel and power generation, as well as ample rapid runway repair capabilities, are also crucial.

Recommendations

The war in Ukraine and the growing potential for a conflict in East Asia highlight the need to address critical shortfalls in both active and passive defenses for U.S. air bases. Congress, DOD, and the Air Force should consider the following:

- Develop, codify, and implement the Agile Combat Employment concept. ACE is a core element of effective air base defense. Altering the Air Force’s posture in forward areas by dispersing its operational forces is a key passive air defense element. The Air Force should define standards for Resilient Forward Basing to guide future active and passive air defense investments and budget requests. The Air Force must also identify the measures of performance and effectiveness necessary to assess air base resilience.

- Fund a dedicated air base defense program. In the face of significantly increasing adversary threats, these requirements cannot simply be carved out of existing budgets. Additional funding is needed to address urgent operational requirements for the defense of U.S. air bases. Congress must fund these capabilities at levels commensurate with the value that air power offers to theater operational plans, alliances and partnerships, and deterrence.

- Establish interservice agreements on air base defense. Unless the Air Force is manned, trained, and equipped to provide its own ground-based air defense, the Air Force must rely on its service partners for these capabilities. The Army—and the Navy in littoral regions—should provide theater-wide, high-altitude air and missile defense. The Army also should provide intermediate- and short-range ground-based air defenses near air bases. Should such an arrangement prove impractical, Congress should reallocate resources to the Air Force to defend its own air bases.

- Fund, build, and deploy substantial passive air base defenses. A budget-minded Congress should consider that passive defenses such as hardening, camouflage, concealment, and deception are the most cost-effective measures against air and missile attack. Passive defenses will drive up adversary attack costs, creating a tangible deterrent.

- Invest in rapid runway repair and air base reconstitution capabilities. Sustained adversary attacks on runways threaten to close air bases for extended periods and effectively suppress combat sortie generation. Categorized as a passive defense measure, rapid runway repair is also an indispensable and cost-effective capability necessary to return air bases to operational status.

- Invest in space and airborne early warning and long-range airborne kinetic and non-kinetic capabilities for air base defense. An effective air base defense operational concept requires early warning against low-flying inbound threats such as hypersonic glide vehicles, cruise missiles, and drones. Early warning provides advantages for defenses such as surface-to-air missiles, electronic attack, and directed-energy weapons, and it may enable rapid response measures such as quickly sheltering aircraft or closing blast doors. Combining early warning with an airborne air-to-air engagement capability also creates an outer ring of long-range defense against inbound threats to air bases.

- Significantly increase investments in cost-effective air base air defense sensor and C2 capabilities. Coordinating effective responses to attacks is a decisive component of an effective air base defense. Air defenses must have a redundant and survivable sensor and C2 capability to allocate the right defensive capabilities and weapons at appropriate ranges to defend against sustained enemy attacks.

- Significantly increase investments in a diverse arsenal of integrated active defense capabilities, especially cost-effective, short-range defenses. The Air Force and the Army must invest in intermediate-range and short-range capabilities to supplement systems like THAAD and Patriot surface-to-air missile systems. Shorter-range systems deployed in larger numbers should include surface-to-air missiles, air defense cannons with maneuverable projectiles, directed-energy weapons, and electronic warfare capabilities.

- Pursue additional studies, modeling, experimentation, and air base defense exercises. The Air Force should continue to study and develop the most capable, cost-effective mix of passive and active air defense. Fighting from front-line air bases may mean the difference between winning and losing in a future conflict. The U.S. Air Force must be capable of operating from well-defended forward bases. If not, allies and partners may question the ability of the United States to deter and dissuade would-be adversaries. The U.S. and allied way of war demands a capable Air Force that can operate inside adversary threat envelopes and rebound from potential attacks. This is a no-fail mission. Making necessary investments in capable, cost-effective, and combat-relevant air base defenses is vital to U.S. national security.