Amid unprecedented amounts of electronic warfare in Russia’s war on Ukraine, there is no doubt that the Russians are jamming GPS and other satellite-based navigation systems around the Baltic Sea. Earlier this year, the interference forced a temporary halt of commercial air traffic at a major commercial airport after flights had to be diverted enroute.

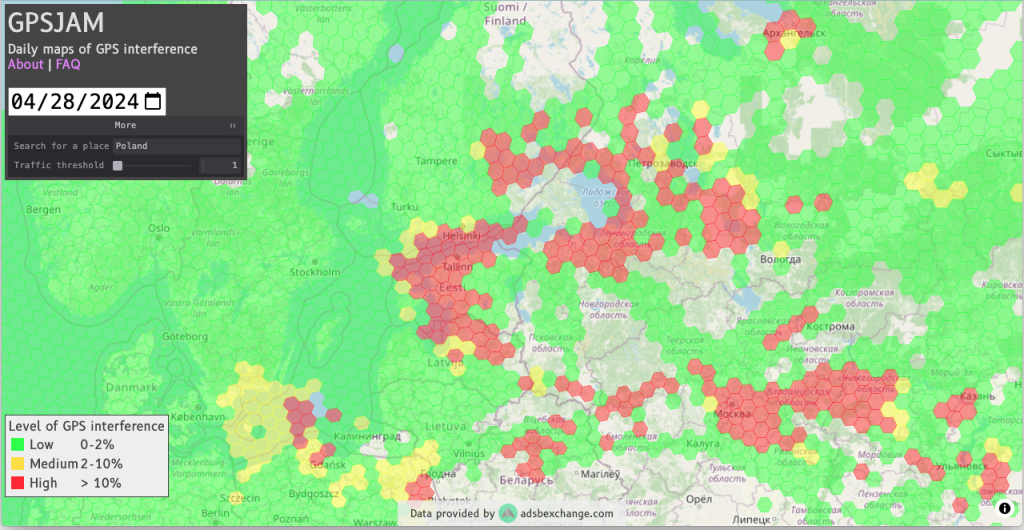

“We know that Russia has been jamming GPS signals,” Estonian Minister of Foreign Affairs Margus Tsahkna said, explaining why commercial flights to Tartu, the country’s second largest airport, had to be suspended. The jamming has affected not just Estonia, but parts of neighboring Latvia and Lithuania, sites in Finland and Sweden across the Baltic Sea, and as far afield as Poland and Germany, according to publicly reported data from commercial aircraft.

It is also pretty clear how Russia is doing the jamming, which involves simply broadcasting a more powerful signal on the same frequency used for GPS. Since the real GPS signals come from satellites 12,500 miles above the Earth’s surface, they are easily drowned out by much closer terrestrial broadcasts. According to experts, technical inferences from public data sources bear out Tsahkna’s claim that the jamming is coming from three ground-based locations in Russian territory, including the port enclave of Kaliningrad, sandwiched on the Baltic coast between Latvia and Poland.

But when it comes to the question of why the jamming is happening, things become fuzzier.

Is it just spillover from Russian air defense and force protection measures—jamming GPS so Ukrainian drones can’t use it to find their Russian targets? Or is it something more deliberate, targeted at GPS in non-combatant countries?

The answer matters because how America’s European allies respond to Russian provocations like GPS jamming is likely to shape whether or how the Ukraine conflict spreads.

GPS interference for civilian users as a spillover effect from jamming operations in active combat zones has been endemic in parts of the Middle East for more than a decade. And experts agree that such jamming is generally lawful under the Geneva Conventions, even when it impacts commercial air traffic. Deliberate, albeit non-kinetic, attacks on the civilian infrastructure of non-combatant nations would be a different matter, and likely illegal under international law.

More Ambiguous Picture

“This attack on GPS is part of a hybrid action to disrupt our lives and to break all kinds of international agreements,” Estonia’s Tsahkna said, definitively linking the GPS jamming to cyberattacks, mysterious fires at warehouses and shipyards, and the other elements of Russia’s “gray zone” warfare campaign identified by European leaders. He said the campaign was designed to punish NATO member nations for supporting and aiding Ukraine without triggering the Article Five threshold that would invoke military action by the alliance.

Officials from Sweden and Lithuania have also publicly called out the jamming as a hybrid attack, noting Russia has a history of expertise in electronic warfare techniques like GPS jamming.

But others aren’t quite so sure.

Technical data from civilian flight safety agencies in the region, including Estonia’s own, paint a more ambiguous picture.

Europe’s non-governmental Centre of Excellence for Countering Hybrid Threats (known as the Hybrid CoE) in Helsinki, Finland, concluded that the jamming is more likely a spillover impact from Russian efforts to prevent GPS-guided drone attacks on its own forces and key installations like power stations.

“The danger to civil aviation is real and serious,” said Tapio Pyysalo, head of international relations at the Hybrid CoE, “But the way we define hybrid threats is that it’s something with a strategic intent behind it actually trying to hurt the target. That’s not what we’re seeing here.”

Finnish government officials told Air & Space Forces Magazine that their analysis of technical data reached the same conclusion.

A senior NATO commander echoed the Hybrid CoE characterization. “Look at the number of flights whose GPS systems are now being affected by basically careless Russian jamming activity,” said British Air Marshall Johnny Stringer, the deputy commander of NATO’s Allied Air Command. He accused Moscow of being reckless about the collateral damage it was causing through electronic warfare operations.

“The Russians have a very different perspective on how to set the bar in using these kinds of offensive operations in the electromagnetic environment, than quite rightly, we would hold ourselves to,” Stringer said.

The Estonian Embassy in Washington, D.C., referred Air & Space Forces Magazine to the Consumer Protection and Technical Regulatory Authority, a civilian agency in the capital city Tallinn that regulates radio communications and the use of radio spectrum.

In an emailed statement, Oliver Gailan, head of the Electronic Communications Department at the agency, didn’t directly answer questions about whether the jamming was a spillover effect or a deliberate attack, but he did confirm that there appeared to be no interference at ground level, so smartphone location-based services, and other technologies like ATMs that rely on GPS and other Global Navigation Satellite Systems continued to work fine.

Gailan said the interference was a violation of Russia’s obligations under the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) treaty, of which it is a signatory. “Estonia has already made a formal notification to the ITU,” he said.

The spokesperson for the Russian embassy in Washington, D.C., did not immediately respond to an email requesting comment.

‘Significant Challenge’ to Airline Safety

There has been no official impact assessment, but the Russian jamming affects an average of 350 commercial flights per day, according to a tally compiled from open-source data by a pseudonymous researcher on Twitter, whose work has been cited by the British Ministry of Defense.

There are fallback navigational techniques, and commercial flights resumed to Tartu airport last month after GPS-alternative technology was installed there. But the alternatives to GPS lack its accuracy and convenience, and jamming it “poses significant challenges to aviation safety,” according to the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA).

Nonetheless, because GPS is being used in combat by Ukrainian forces, it is “overwhelmingly likely” that it is a legal target for Russia, explained retired Marine Corps Lt. Col. Kurt Sanger, a career military lawyer who finished his service in November 2022 as the deputy judge advocate general for U.S. Cyber Command.

The Geneva conventions generally require combatants to weigh whether the impact on non-combatants of a military strike or other operation will be greater than is warranted by the military advantage gained from it—the so-called proportionality test. The GPS jamming seen in the Baltic has not caused any direct loss of life or destruction of property, Sanger said, so even though the economic costs might be severe, it is hard to see how it would fail such a test.

However, he added, the U.S. does hold itself to a higher standard than that set by international law in planning cyber operations. “As a prudential matter, and as a matter of DOD regulation, we had to consider more than just the casualties and property destruction international law requires,” he said of his time at CYBERCOM.

U.S. command staff might include an analysis of the economic costs of a cyberattack, for example. Even the possible effect on public opinion was weighed. “It’s good to know who your operations are going to upset and what kind of condemnation you’re going to draw,” Sanger said.

A Distinction Without a Difference

Veteran former officials on both sides of the Atlantic expressed a degree of impatience with the debate about the exact reason for the jamming.

“Typical Russian plausible deniability BS,” said one former senior U.S. defense official. The official, who asked for anonymity to preserve business relationships while speaking candidly, argued that the spillover vs. hybrid debate was a distinction without a difference, and a distraction to boot.

The spillover effects enable Russia to study how NATO countries respond to a GPS blackout, while allowing them a fig leaf of plausible deniability in the court of public opinion, this official said. Tartu is Estonia’s second largest airport. “That’s like Boston or LAX closing for a month, and we’re arguing about what it might mean that they didn’t also shut down the ATMs,” the official said.

In fact, the absence of interference on the ground is most likely a product of physics—a side effect of the way that ground-based jamming signals propagate outwards from their source. “Think of it like a speaker or a flashlight pointing upwards,” said Mike McLaughlin, a retired U.S. Navy intelligence officer who worked on GPS jamming. “The waves heading straight up vertically don’t encounter interference. The closer you get to the ground, the more likely the [jamming] signal will be blocked by terrain like hills or mountains.”

Retired Col. Aapo Cederberg, who held senior security positions in the Finnish civilian government and is now in the private sector, said the uncertainty was an effect of the nature of gray zone tactics.

“If you are only using open-source information, it might be hard to tell [spillover vs. hybrid attack] But if you know the principles and modus operandi of the Russian hybrid warfare doctrine you can make an evaluation. Many intelligence services have been clear that this is a hybrid operation,” he said.

Russian hybrid warfare operations always included a cognitive, or information war aspect, Cederburg explained, adding that Moscow might be deliberately creating open source data points (like the absence of interference at ground level) which cast doubt on the purpose or cause of the jamming.

“Russians are always doing their hybrid operations in a way that creates a fog of uncertainty. That’s the beauty of hybrid warfare, and this is very difficult for journalists and think tanks to understand, but it is a critical element of the hybrid warfare concept,” he said.

That informational uncertainty attached to gray zone activities put the role of political leadership front and center in determining the response, said Pyysalo, from the Hybrid Center of Excellence—including the question of whether and when to attribute hybrid activity.

“That’s what makes attribution such a political decision,” he said. “With often inconclusive information, you actually have to be able to say that it was this state behind this act, although we’re not absolutely sure.”

Additional reporting provided by Pentagon Editor Chris Gordon.

Editor’s Note: This story has been corrected to note that although commercial flights at Tartu Airport were suspended in May, the airport remained open and was used by private planes and medevac helicopters that landed without the aid of GPS.