The House Appropriations Committee, frustrated with soaring costs and schedule slips on the new Sentinel intercontinental ballistic missile, wants to slash the Air Force’s 2025 budget request for the program by $324 million. But lawmakers also want the service to leave program leaders in place longer and explore an old idea for the Sentinel: giving it some kind of mobility to complicate enemy targeting.

The committee, in its mark of the 2025 defense appropriations bill, would still direct some $3.4 billion for Sentinel in the coming fiscal year. And in accompanying report language, lawmakers noted their prior support for the program to the tune of more than $12.5 billion since 2020.

Ultimately, however, they want to cut the Air Force request by around 8.7 percent because of “insufficient justification and program uncertainty for execution needs in 2025,” which typically means it doesn’t think the Air Force will spend as much as it planned in that year.

Sentinel is currently undergoing a review, having substantially overrun its cost and schedule estimates. The Air Force estimates the Sentinel will cost 37 percent more than expected and is now running two years behind schedule.

Under the Nunn-McCurdy law, the Secretary of Defense must certify that there is no alternative to the Sentinel or he must cancel the program. Defense Secretary Lloyd J. Austin III is expected to certify the Sentinel as essential and should continue in early July, after a mandated investigation and report of how the overrun occurred. However, the Air Force has said it is not suspending any activities of the program and is proceeding with it while the review takes place.

“While supportive of the capability, the committee was stunned to learn about the critical Program Acquisition Cost breach of at least 37 percent and an average Procurement Unit Cost breach of at least 19 percent that were determined following a review of the program in December 2023,” the House Appropriations Committee wrote in its report.

Even while noting the challenges inherent in such a massive program—requiring development and testing of a new missile, rehabilitation of more than 150 silos with new concrete, wiring, and a secure communications system to command and control it—lawmakers said they are “concerned that the issues driving the critical overruns were not identified sooner, the level of flawed technical assumptions, and the management continuity of the program.”

Not having long-term leadership managing Sentinel is “contributing to poor program performance, cost overruns, and schedule slips,” the lawmakers suggested. The committee directed the Government Accountability Office to study how the turnover in program managers has affected the its performance.

But the HAC also indicated it won’t simply rubber-stamp continued work of the Sentinel.

“The committee expects a full discussion on all statutorily required aspects of the Nunn-McCurdy review; specifically alternatives considered, including those recommended” in a 2023 report from the “Congressional Commission on the Strategic Posture of the United States.”

Along those lines, lawmakers want another report from the Secretaries of Defense and the Air Force, along with the head of U.S. Strategic Command—within six months from passage of the defense bill—”on the most feasible recommendations highlighted in the Commission’s report related to interim capability to augment a potential capability gap caused by delays in Sentinel, to include the feasibility of fielding some portion of the future intercontinental ballistic missile force in a road-mobile configuration.”

The report is to include an assessment of “technical attributes, cost, timeline, workforce limitations, and treaty considerations.”

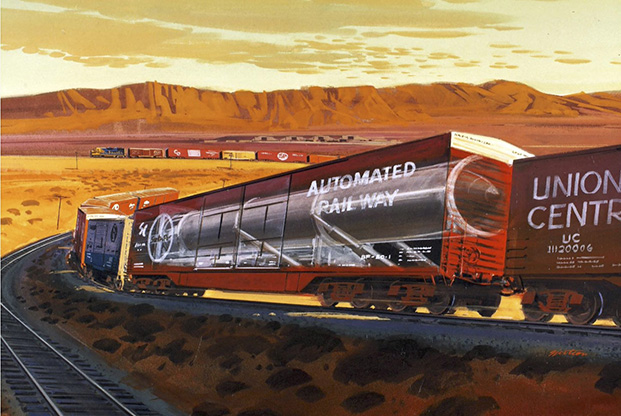

The Air Force extensively explored mobile options for the LGM-118 Peacekeeper missile (previously called the “M-X”), which was fielded in 1985 and removed from the inventory under the START treaty in 2005. Such options included moving the missiles around quickly and unpredictably from one silo to another; this shell game would force the Soviet Union to target all silos, not knowing which were occupied and which were empty. “Rail garrison” would have disguised the missiles as commercial freight on rail lines, able to stop, elevate and launch on short notice, depriving the Soviets of a certain target.

Another option involved towing missiles around on transporter-erector-launchers (TELs) and moving them routinely but unpredictably so that their location was not fixed, removing the certainty that precise incoming missiles would catch them all in a first strike. The Air Force took this approach to the point of prototyping competitive TELs from Boeing and Martin Marietta. Other alternatives included moving the missiles around in underground tunnels or dropping them out the back of a C-5 Galaxy transport.

Given the inability to find consensus with Congress on a mobile basing system, the Reagan administration ultimately opted to put the first 50 Peacekeepers in Minuteman silos, leaving the mobility issue unresolved. In 1991, the mobility concept was dropped.

Former Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Welsh told Air Force Magazine in 2013 that a road-mobile option for Sentinel, then called the Ground-Based Strategic Deterrent (GBSD), had been determined to be unnecessary, given silo hardening and the need for an enemy to target hundreds of silos without any certainty of total success. Fixed-site ICBMS were the most responsive and lowest-cost element of the nuclear triad, Welsh said.

The Soviet Union—and now China—have put a substantial portion of their strategic nuclear missiles on mobile launchers as well as in silos.

In yet more homework for the Air Force, the HAC wants to mandate quarterly updates from the Secretary of the Air Force “on the land-based nuclear capability.”