The ABCs of air-to-air combat, Basic Fighter Maneuvers, are taught to Air Force fighter pilots early in their careers. But in 2018, F-15E pilot Matthew Ross nearly failed out of an instructor upgrade course because his BFM skills had gone to seed; he had just spent six months flying close air support over the Middle East, and before that he spent six months learning flight command for a multiship flight lead upgrade.

“I was supposed to be good enough to teach a student, and I really struggled at it,” he told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

In an era of shrinking aircraft fleets, nearly every fighter pilot must know how to fly a wide range of missions. But the Air Force’s software tools for tracking those skills are decades out-of-date and often rely on subjective assessments, which hinders combat readiness and wastes scarce resources, Ross said.

He’s not the only one calling for smarter use of data. In February, Air Force Vice Chief of Staff Gen. James C. “Jim” Slife said the service was missing out on a “decisive advantage” in training, operations, maintenance, and logistics offered by the data produced by digital flight systems.

”There’s lessons learned built into that,” Slife said about the terabytes of data produced by F-35 flight systems. “There’s mistakes than can be learned from in there, there’s the bad radio call, there’s the signal we’ve never seen before.” That data could be used “to feed our algorithms, to power accurate AI models.”

The head of Air Education and Training Command made a similar call in May to use data to make the training system more efficient.

“We don’t have time to accept wasted time in training pipelines, [and] substandard developmental and training paths,” Lt. Gen. Brian S. Robinson said May 7 at the Air Force Modeling & Simulation Summit in San Antonio, Texas. The benefits will also spill over into operational wings when they train at home, he said.

Better tools exist which could track each pilot’s strengths and weaknesses more closely using objective data and help tailor their training accordingly, Ross said. It would also help squadron commanders better understand their unit’s readiness on a near real-time basis.

“The Air Force understands that there’s skill decay, and right now the way it deals with it is just a generalized statement of ‘you need a few months to get your skills back,’” said Ross, who has since left Active-Duty and joined the Air National Guard. “There’s no reason to act like that now, because we have such powerful techniques and models that can do it at a more individualized level.”

The Status Quo

While Air Force fighter squadrons use plenty of objective metrics to gauge the health of their aircraft, the list is not so long for aviator training. Generally, less experienced pilots must fly nine sorties and three simulator events per month and fill out a training accomplishment report for each, while more experienced pilots are required to fly fewer sorties. Commanders then review the reports once a month to determine if the squadron is trained or needs more practice in certain mission sets, but frequently the assessment boils down to whether each pilot hit their minimum number of sorties.

The problem with this approach, Ross argued in a commentary piece for War On the Rocks in January, is that the commander’s assessment is a best guess based on imprecise data compiled and assessed on just one day each month.

“The commander could decide to declare, on a per-pilot basis, who is mission-ready for each mission,” Ross wrote. “However, unless a commander has intimate knowledge of every skill of every pilot, then these determinations are—at best—a guess.”

In a different era, this approach may have been the best one, he said, but advanced analytics and artificial intelligence can help a commander gauge his or her pilots’ abilities in every mission task on-demand. The Air Force-MIT AI Accelerator already has an AI-infused scheduling program called NICE that would work with what Ross is proposing, he said.

“We could make this system very easy for commanders, scheduling officers, and the director of operations so they can schedule the appropriate people on the right days for the mission sets that they need to maintain their readiness,” he explained. “We can do this in near-real time, and day-to-day have an assessment of where the squadron is with objective data.”

The Solution

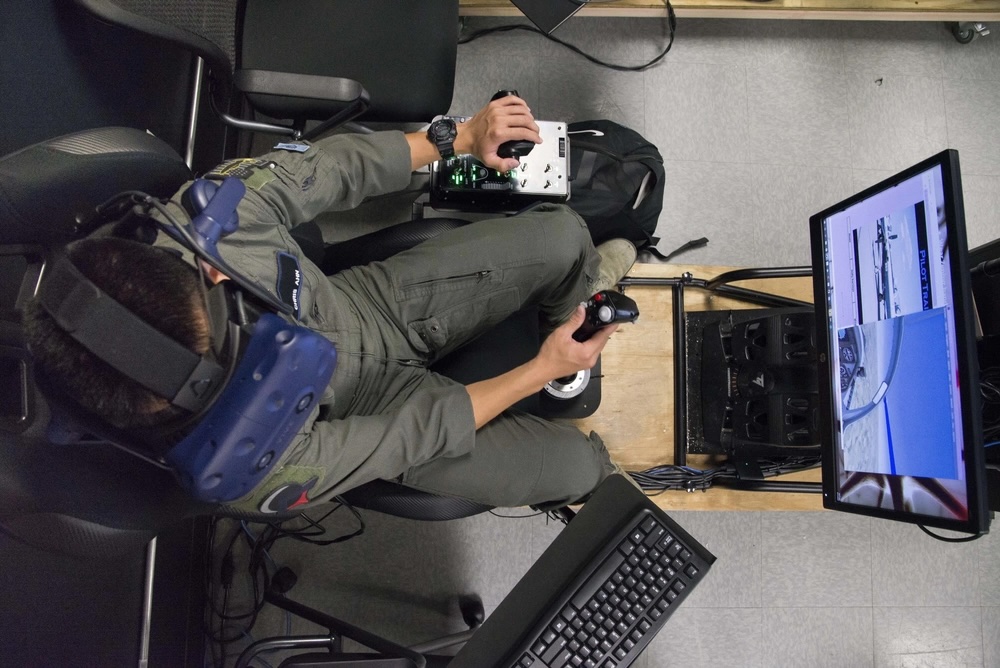

The Air Force is already using a similar system in predictive maintenance, where artificial intelligence analyzes a wealth of data to create maintenance alerts for each jet. Predictive training software could do the same thing by analyzing a pilot’s past performance, predicting how quickly their skills decay, then recommending how often the pilot needs to train in which skills.

“Squadrons will know exactly what skills have decayed for each pilot to the point that the pilot would be unable to reach the mission outcomes necessary for victory,” Ross wrote. “Capt. Stephens may not be ready for a defensive counter-air mission because his flight leadership skills have deteriorated, while Lt. Smith may not be ready for the same mission set because her defensive timeline knowledge has decayed.”

As an example of the power of analytics, Ross pointed to his own work with the 4th Training Squadron, which writes the syllabus for the Strike Eagle formal training unit. By looking closely at training data, he and his colleagues at Air Combat Command and the Air Force Research Laboratory proved a connection between FTU performance and a specific skill taught early in undergraduate pilot training.

“We were able to show that if a student performed poorly throughout the T-6 syllabus on inflight decision-making, that they would fail out of the FTU, which is extremely expensive for the Air Force and also now you’re missing a fighter pilot,” he said. “I wish we had more detailed performance data at the time to prove more specific causality.”

In the future, granular data and AI-driven analysis can show even more closely how early training and retention in certain skills impacts pilots throughout their careers. Not all pilot skills can be measured objectively; Ross emphasized that human assessment will still be vital in areas such as a pilot’s decision-making. Still, better software can help free up brain space so that human instructors can focus on the bigger picture.

“We don’t want the instructors worried about ‘did you do this small thing right or wrong?’” Ross said. “We want the instructors doing things only humans can do, which is ‘let’s talk about your decision-making during this part of the sortie.’”

Beyond Pilots

Better learning management systems could help other career fields beyond aviation. When a maintainer replaces a jet engine, such a system could track how effectively they did it and other data points that paint a picture of the maintainer’s abilities.

Adopting such systems in the short term would not be difficult, said Ross, whose company Eduworks is already working with Air Education and Training Command and Naval Air Systems Command.

“I don’t want to give more work to anyone who’s Active-Duty,” Ross said. “What that means is whatever they’re filling out right now, whatever inputs they have into the system, I don’t want to add any more. I just want to scrape the data and I want to export it into something that is useful for them.”

The benefits could prove decisive.

“Individuals determine the outcome of combat,” he wrote, “and individual readiness determines the likelihood of that outcome.”’