The Enterprise Test Vehicle program the Air Force and Defense Innovation Unit announced June 3 will explore high-rate-of-production technologies and platforms for testing other systems—but it is not a part of other similar Pentagon programs like Replicator or Collaborative Combat Aircraft, and it is not meant to produce prototypes for weapons, officials told Air & Space Forces Magazine.

However, a breakthrough success in lowering cost and speed of production could pave the way for a weapons program, a Pentagon official said.

“If they show us something remarkable … of course we would consider adapting it” as a weapon, the official said. “But that’s not the main idea here.”

The program is “not the Air Force’s ‘Replicator,’” added the official, referring to Deputy Defense Secretary Kathleen Hicks’ signature initiative to select and mass produce drones and autonomous systems from across the services, the official said. The Air Force declined comment on whether the ETV is its submission for Replicator.

Other officials said it is not part of the CCA Program, either, although the data collected will inform that effort.

Four ETV competitors were announced June 3: Anduril Industries; Integrated Solutions for Systems, Inc.; Leidos Dynetics; and Zone 5 Technologies.

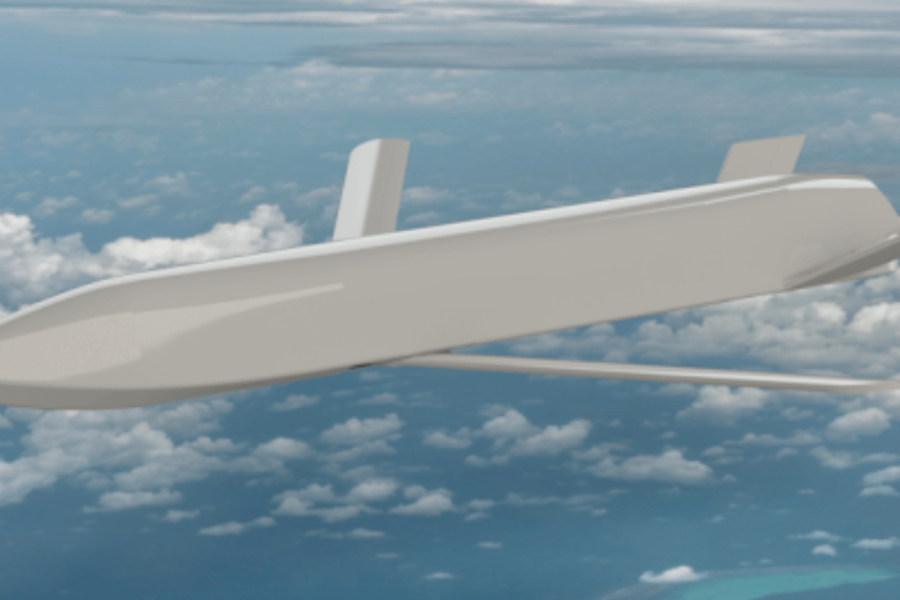

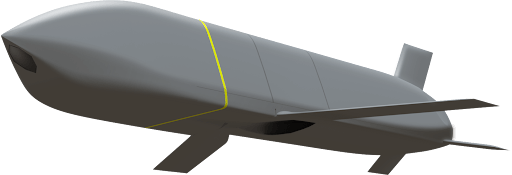

The goal of the ETV is to produce inexpensive, rapidly-producible air vehicles that can serve as test platforms for modular gear that could be used on weapons or platforms. Part of the program is to achieve high-speed production by avoiding the use of hard-to-get materials or components requiring long lead time. Using commercial, off-the-shelf (COTS) components is a priority.

“The Enterprise Test Vehicle (ETV) will serve as a research and development platform for the USAF to explore open system architecture and modularity concepts,” a spokesperson said.

Its primary purpose “is to demonstrate the test vehicle’s adaptability and manufacturing scaleability during design and proof of manufacturing,” she added. “The intent is to certify the ETV for use and have it as a rapid, affordable option for program offices to test out new capabilities at the subsystem level without having to [recertify] it for flight test. The ETV will be used to integrate … COTS subsystems to prove the integration and affordability of the system concept.”

The platform—or platforms—chosen after the competitive demonstration will be those best able to use modularity “to more easily integrate, demonstrate, and reduce risk for additional subsystems (e.g., affordable engines, ISR seekers, or communications suites) or other weapon system variants,” the spokesperson said.

The program will also use ETVs to explore “maturing different options for weapon employment, to include palletized employment, collaborating air launch, ground launch and others,” she added.

The Air Force has explored palletized employment using stacks of AGM-158 Joint Air-to-Surface Missiles dropped out of the back of cargo aircraft. Presumably, the ETV would be a less costly subject for such tests.

The Air Force spokesperson said the first ETV demonstration will be a low-cost cruise missile design called “Franklin” but did not say which contractor’s vehicle this referred to.

In a solicitation to industry for the ETV published last year, the DIU emphasized the program’s focus on developing rapid production capabilities for new munitions.

“The Department of Defense replenishment rates for unmanned aerial delivery vehicles are neither capable of meeting surge demand nor achieving affordable mass,” the solicitation stated. “The current design and manufacture of airborne medium-range precision delivery vehicles are complex, costly, and limited by historically slower production rates due to exquisite components and labor-intensive manufacturing processes. Narrow supply chains, proprietary data, and locked designs result in a lengthy timeline to transition new technology into usable capability and limit production and replenishment rates.”

The DIU said it wanted “solutions to develop, demonstrate, and fly a modular open architecture vehicle that will accelerate capability development and fielding across all weapons programs by enabling the integration, testing, and qualification of different subsystems, capabilities, and materials. The objective is to demonstrate an aerial platform that prioritizes affordability and distributed mass production.”

It specified vehicles having a range of 500 nautical miles with a minimum cruise speed of 100 knots, “capable of delivering a kinetic payload,” and ready for test seven months after contract award.

Although the DIU and Air Force announced the ETV contractors in early June, they also said demonstrations would begin this summer, suggesting the contracts were awarded around January.

The solicitation also specified demonstration of “an air-delivered variant (e.g., gravity dropped/launched from the back of a cargo aircraft).”

Finally, the DIU sought platforms “capable of bulk transportation and employment in large quantities.”

The DIU’s solicitation noted that “multiple variants may be developed following a successful initial flight test.” Designs that can be produced in different locations, potentially including foreign partners with minimal reliance on special tools and test equipment will be prioritized.