Biggest Space Flag Exercise Ever

By Greg Hadley

The Space Force’s premier exercise was restructured and expanded for its latest iteration, as planners emphasized Guardians’ ability to integrate into a larger operational plan.

The three-week Space Flag 24-1 brought together 400 participants at Schriever Space Force Base, Colo., in April—up from 250 or so in the biggest prior Space Flag event.

“It is important that Space Flag expands,” Lt. Col. Scott Nakatani, commander of the 392nd Combat Training Squadron, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “It needs to expand to cover down all of the mission areas and those critical units that are preparing to be presented. So we expanded greatly. We definitely maxed out our spaces.”

More than size, Space Flag also expanded beyond tactical training for the first time, including operational support for warfighters.

“Space Flag in the past has been tactical mission plan, tactical execution—plan, execute, plan, execute,” said Capt. Lane Murphy, exercise director. “So now it’s kind of transitioned to, instead of advanced training, it’s more operational readiness to execute effective support of an [operations] plan.”

In prior years, mission planning and execution were conducted on the tactical level, but this year, the entire first week was devoted to developing overarching operational plans, which were then passed on to mission commanders. The next two weeks focused on collaborative planning efforts from approximately 20 units across Space Operations Command to execute the plan, which were then tested in “fly-out” simulations against a thinking adversary, according to a Space Training and Readiness Command release.

“We did that to be more realistic,” Murphy said. By bringing planners and different operators together, he added, teams can see how their actions affect other units and adjust accordingly.

Nakatani declined to say exactly what scenarios Guardians faced in this Space Flag, but he did say they were meant to emphasize integration into broader operations.

“It was informed by two real world O-plans, and we based them off of the most likely and most dangerous intelligence assessments of how those O-plans would execute,” Nakatani said. “And this is the first time that we have gone down a hard O-plan-informed scenario. We may have previously seen tasks that would be called out in an O-plan make their way into Space Flag. But this is the first time that we ran down as though the forces were expected to support an ongoing operation.”

Space Flag’s evolution seeks to align the exercise with the Department of the Air Force’s broader effort to “reoptimize for great power competition,” Nakatani added. Back in February, the department announced among its 24 specified decisions that it wanted to “conduct a series of nested exercises in Space Force that increase in scope and complexity, fit within a broader DAF-level framework, and are assessed through a service-level, data-driven process to measure readiness.”

Space Flag was the first major example of that effort.

“Space Flag still teaches integrated mission planning, but it’s more focused on how those space forces come together into an integrated sortie to meet combatant commanders’ intent,” Nakatani said. “And all of that’s directly in line with our direct marching orders, our new direction from the Secretary, from the CSO.”

China’s ‘Unprecedented’ Growth in Space

By Greg Hadley

A little less than three years after then-U.S. Strategic Command boss Adm. Charles Richard warned of China’s nuclear forces experiencing a “strategic breakout,” the Space Force’s top intelligence officer says the People’s Liberation Army has done the same in space.

“The PLA has rapidly advanced in space in a way that few people can really appreciate,” Maj. Gen. Gregory J. Gagnon said May 2 at the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. “I tried to think about historical analogies, about rapid buildups. I haven’t seen a rapid build-up like this. I was thinking about World War II, but even as I was looking more broadly, an adversary arming this fast is profoundly concerning.”

Richard’s assessment of Chinese nuclear capabilities in August 2021 came around the same time that reports first emerged of the PLA building massive nuclear silo fields and has become an oft-repeated term used by lawmakers and Pentagon officials ever since.

In recent months, top military space leaders started using similar language.

“Admiral Richard … labeled the moniker ‘breakout pace’ for nuclear forces. He talked about the fact that, we thought they’d have 500 warheads, but they’re rapidly getting to 1,000,” Gagnon said. “The breakout pace in space is profound.”

Gagnon’s comments came a week after U.S. Space Command boss Gen. Stephen N. Whiting said during a visit to Japan and South Korea that China is moving “breathtakingly fast” in space and only weeks after Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman spoke of an emerging “sensor-shooter kill web” in China that he said “creates unacceptable risk to our forward-deployed force.”

China is now prepared to use space against the U.S. as the U.S. has leveraged its space capabilities against others.

“For the last two years, they’ve placed over 200 satellites in space, both years,” Gagnon said. “Of that, over half of them are remote sensing satellites—remote sensing satellites that are purpose built to surveil and do reconnaissance in the western Pacific and globally. … And the purpose of reconnaissance and surveillance from the ultimate high ground is, of course, to inform decisions about fire control for militaries. It’s to provide indications and warning of [U.S.] Sailors, Marines, Airmen trying to move west, if directed, to defend freedom.”

Using space for ISR is something only the U.S. has been doing for years. Now, though, “that monopoly is over,” Gagnon said.

And like the U.S., the Chinese are not content with only a few, technologically exquisite satellites, Gagnon warned. Rather, they are putting up so many satellites to proliferate just like the Space Force is trying to do—making it harder for an adversary to block the ISR and targeting capability.

It is, Gagnon warned, “an architecture that’s designed to go to war and sustain at war.”

The U.S. Space Force is countering China by adding sensors and a new squadron—the 75th Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance Squadron—to enhance U.S. targeting of adversaries’ space assets, networks, and ground stations.

China and others account for some 1,000 “priority” satellites in orbit, and the Space Force has some 600 sensors to track them. That marks rapid growth from a few dozen just a few years ago, but necessary given the rising level of China’s space activity. Five years ago, space leaders pushed out “six to seven maneuver alerts a month,” Gagnon said. “Today, we’re putting out 11,000 a month.”

USSF Eyes LEO for Moving Targeting Indication

By Greg Hadley

The Space Force and NRO want to build and deploy a constellation of targeting satellites in low-Earth orbit, the USSF’s top intelligence officer said May 2.

The two organizations have been working for months to develop satellites that will provide moving target indication (MTI) for troops on the ground and in the air to keep track of targets and replacing old Air Force platforms that officials say would not survive in a contested environment. But many details of the plan remain under wraps.

Speaking with the Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies, Maj. Gen. Gregory J. Gagnon, vice chief of space operations for intelligence, did not offer specifics on how many satellites will be needed or when they will launch, but he did lay out the basic framework for how they will work and how Guardians will use them to assist combatant commanders around the globe.

“This will be an asset that’s in LEO,” Gagnon said. “You think about the numbers of these that you will buy, and you think about proliferating this architecture so that it can be difficult to destroy multiple of them … and so the fact that you proliferate your architecture and don’t just have like six satellites that can do this—I won’t give you the real number—but you can have lots of satellites that do this. It makes it difficult for them to disrupt.”

The Space Force is already building proliferated constellations for transporting data and missile warning/missile tracking in low-Earth orbit. The hope is that a potential adversary such as China won’t be able to shoot down enough satellites to disrupt the network, thus discouraging it from trying in the first place.

In order for such a targeting solution to work, the Space Force will likely have to buy dozens of small satellites. Spacecraft in LEO don’t stay in one place, and it takes several to provide steady, persistent coverage over an area. On the plus side, small, fast-moving satellites are tough to disable, Gagnon said.

“If you’re lying in the backyard and you’re looking up and something’s going over at LEO, it’s going over really fast,” he explained. “So you have to be able to know what it is, track it, send that firing solution to a firing element, and get that engagement as it’s zipping over you, because you only have a field of view that’s kind of short.”

For decades, the Air Force relied on aircraft such as the E-8C JSTARS and E-3 AWACS for moving target indication, but officials worry those could be easily destroyed in a near-peer conflict. Proliferated satellites are thought to be more survivable, but they require a change in mindset about the very nature of military space, Gagnon said.

“It’s a tactical platform in space, and our use of space as a community has always considered it special and strategic,” he said. “Space is no longer only strategic. Space is tactical. And our adversaries have made it so.”

The shift to tactical raises questions about who will direct and operate the satellites. For years, agencies such as the NRO and the National Geospatial Intelligence Agency conducted intelligence operations from space, but did not focus on real-time targeting. With the shift to tactical, Space Force officials say the combatant commands should have tasking authority over the satellites, with the help of the Space Force components stood up within those combatant commands in recent years.

“The Space Force proposal, since we’re part of the joint force, and we’ve stood up components in each of the combatant commands, is to make sure that our component can service their component partners, whether it’s the Army component, the maritime component, or the Air Force component, with timely, relevant MTI capability based off the direction of their joint combatant commander,” Gagnon said.

Recent media reports indicate there is tension between the Space Force and other agencies about how to fulfill the MTI mission, but Gagnon said he is working with both the NGA and NRO on the problem.

“I have spent the last three days actually out at NGA with [NGA Director Vice Adm. Frank Whitworth] and [NRO Director Christopher Scolese]. We’re in meetings where we’re talking about the best way to optimize taxpayer money that supports the joint warfighting need,” Gagnon said. “Because we must be able to do moving target indicator with sensor control from the warfighters so that they can close the kill chain. That’s our remit.”

Government satellites may not be the only ones providing MTI. Gagnon noted a Space Force pilot program that started last year called “Tactical Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Tracking,” or TacSRT, that created a commercial marketplace for such data. Combatant commanders can go to the marketplace, type in the kind of data they need, and then contractors have 72 hours to respond to the proposal, Gagnon explained.

Vision for Part-Time Guardians Still Fuzzy

By David Roza

The Space Force expects not to have conventional Guard and Reserve forces, but instead to have a single personnel system that enables Guardians to serve on either a full-time or part-time basis. But just how that will work is still unclear.

Part-time jobs could involve test, evaluation, training or planning, and might involve a variety of duty tempos, including temporary full-time status for deployments and multiweek temporary assignments as are common in the Guard and Reserve today.

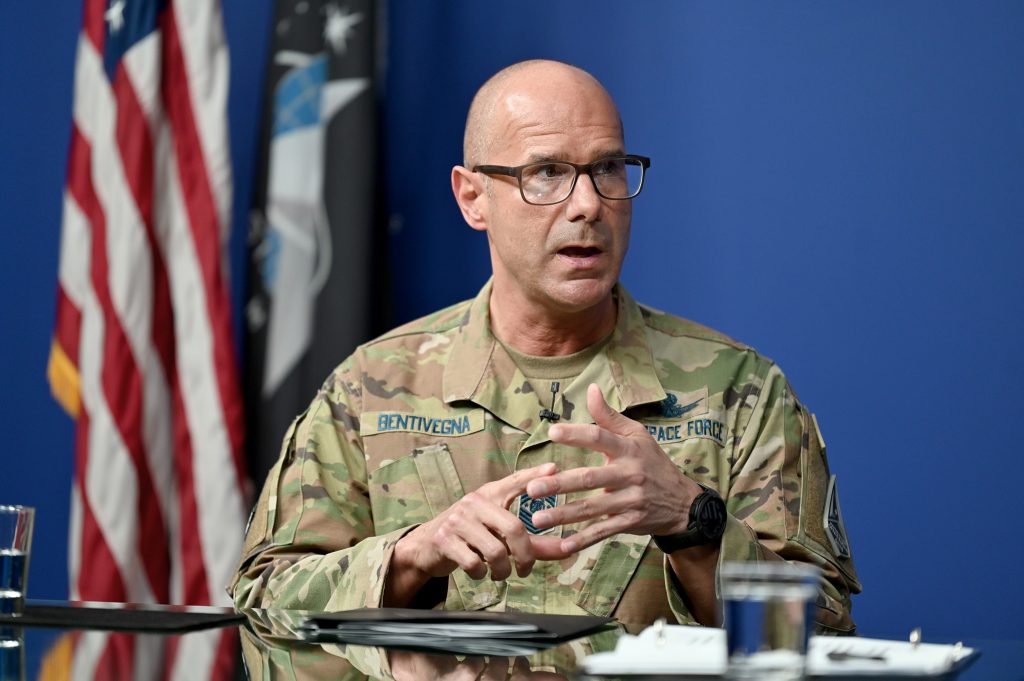

Speaking at an AFA Warfighters in Action fireside chat on May 10, Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force John F. Bentivegna said the service is still working through the details of what a part-time force would look like under the Space Force Personnel Management Act, a bill signed in December. But Bentivegna said the new system will give Guardians the ability to adjust to changing life circumstances more easily, and help them avoid the bureaucratic hoops of switching between components.

“It adds optionality to the Guardians, so we can still leverage that deep expertise that Guardians bring to the table,” he said. It also clears up any chain-of-command conflicts that might arise from having two components in such a small service, which “isn’t necessarily beneficial for unity of command or readiness.”

The Space Force aims to open up full-time positions this summer for currently serving Air Force Reservists. That’s the easy part, Bentivegna said, since the branch already has the pay, benefits, and other systems for full-time Guardians. The tricky part is doing the same thing for part-time Guardians.

“Where we have to work on is: define part-time … and not only defining it, but also how do I pay you, how do the systems track you? We don’t have that build yet,” he said.

The Space Force Personnel Management Act gives the service five years to figure it out, but the top enlisted Guardian said the goal is to move much faster than that, perhaps in a year or so. In the meantime, they are figuring out what jobs would work best under the part-time construct. Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman first hinted at those jobs in a March memo.

“I don’t anticipate part-time Guardians maintaining mission-ready status in 24/7 employed-in-place operations,” he wrote. “Instead, we will leverage their expertise in institutional and service-retained functions like education, training, and test units or key staff positions.”

But Guardians are eager for more details. When asked what concerns he hears most from Guardians about the part-time/full-time construct, Bentivegna said that many of the questions “are based on us explaining our vision on full-time and part time.”

“The employed-in-place mission sets when you have to be combat mission-ready, and the commit phase that we talked about, we don’t know whether or not that really is conducive to a part-time Guardian,” he said. “They may not be, ‘Well, I’m a crew dog and I work shift.’ Maybe that’s not part time.”

Instead, the part-time model “really fits in on deployable capabilities,” Bentivegna explained. “That’s a traditional model where you come on full-time orders from part-time, you spin up, you pack up your gear, you maybe go downrange some place, you do your six or seven months, you come back and reconstitute and then you go back to part time.”

That work might include testing and evaluating a new weapons system or acting as an adversary at a Red Flag or other major exercise for a few weeks, missions which put to good use the expertise part-timers bring from their civilian jobs, Bentivegna said. Now the service has to communicate to Guardians and potential part-timers what that looks like and “paint the vision where they can see themselves.”

“I want to be able to tell those stories and get the part-timers, if you will, excited about where we really need them in the future under this Personnel Management Act vision,” he said.