The Air Force has no shortage of complex problems. And from countering small drones to deterring China on a tight budget, solving these problems can require more than just good ideas: it also means getting those ideas out of the ‘silos’ that can form across the Air Force’s various job specialties. Project Mercury, a program sponsored by Air University, is set up for this exact reason.

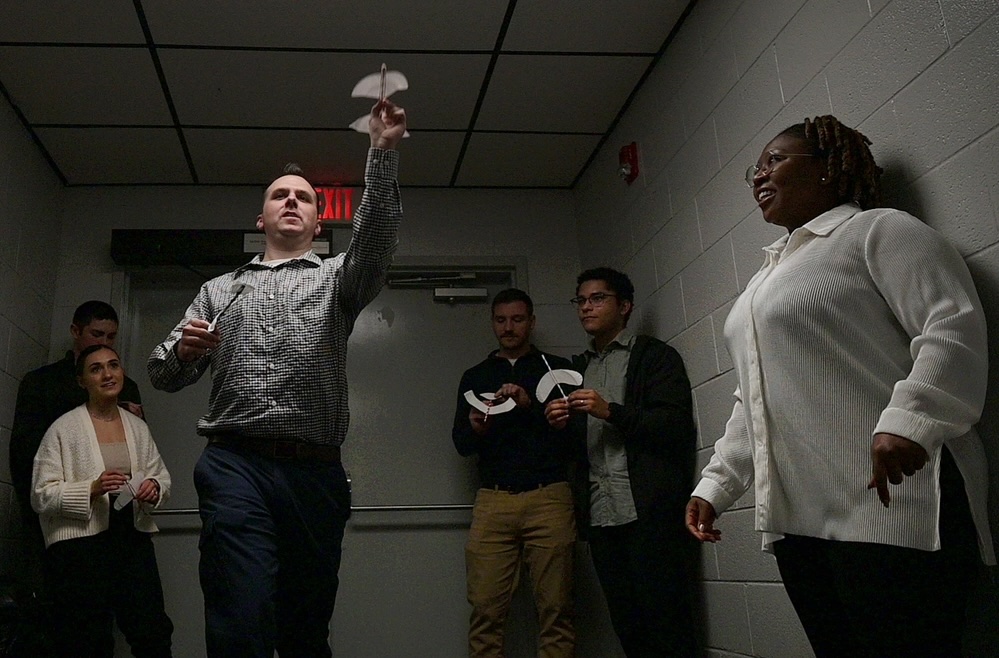

Founded in 2019, Project Mercury takes 40 Airmen, Guardians, and other individuals per “cohort” and divides them into teams of five or six members. For the next 90 days, those team members must work together completing both academic work and an innovation project focused on problems in areas like personnel management, logistics, recruitment, or renewable energy—while still performing their regular full-time jobs.

“One of the things we try to teach our innovators is that nobody cares about your stupid innovation, they care about solving their problems,” Ethan Eagle, head coach of Project Mercury, told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “High-potential go-getters are used to being right, but working together requires humility, it requires you letting go of what you think the solution is and collaborating with creative peers.”

Many programs such as Spark Tank, Spark Cells, Tesseract, and Kessel Run help Airmen and Guardians develop their ideas for solving problems. Part of Project Mercury’s role in that ecosystem is teaching students how to figure out what the problem is in the first place.

“When you get together with a diverse set of people not from the same discipline, you realize ‘Hey, nobody actually agrees what the problem is,’” Eagle said. “Finding that right problem is part of how we differentiate ourselves from the rest of the innovation education ecosystem. We bend minds, not metal, which is a way of saying, ‘leave your pet rock at the door. You’re going to, as a team, find something that everybody agrees with.’ Boy, is that way harder than ‘Hey, I know how to build a better widget.’”

For many students, such as Lt. Col. Julie Janson, their innovation project has nothing to do with their area of expertise.

“They actually go out of their way to keep you out of your specialty area,” said Janson, an information operations officer who worked on personnel management as a Mercury student in 2020 and has since coached several Mercury cohorts. Not knowing the subject makes finding the real problem even more difficult.

“The military is very much like ‘I want to get it done and I want to get it done now,’ so every single team I have experienced jumps right to a solution,” said Janson. “What we are teaching them is to slow down a second and first of all analyze what your actual problem is. That step is skipped so often, and it results in solutions in search of a problem.”

Project Mercury teaches students how to overcome that challenge, in part by reading “The Innovation Code: The Creative Power of Constructive Conflict,” a book by Jeff and Staney DeGraff which explains how to use the tension from different perspectives and personalities to create new ideas.

The program “breaks you out of your comfort zone in so many ways, and one of them is breaking out of your little network of people,” Janson said. “If you just stick within your community, you’re in an echo chamber and you’re not learning anything.”

Breaking down stovepipes is easier said than done in an Air Force where many Airmen spend their careers in one speciality, explained another early Project Mercury student, Col. Steve Marshall.

“People work so hard in their own lanes that they don’t necessarily have the time to go outside of that,” he said. Project Mercury “helps you build your network, and it then becomes much easier to reach across and out of your natural stovepipe.”

Sometimes effective solutions require breaking a few rules. While that’s a tough ask for Airmen trained to obey checklists, orders, and regulations, Marshall pointed out that the Air Force’s founding mythology revolves around mavericks such as Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell.

“We were founded by this group of rule-breakers who looked for a positive change,” Marshall said. “Those people exist, but there’s no way to bring that along and nurture that in any kind of formal fashion, which is somewhat counterintuitive.”

Janson described Project Mercury as a pressure-cooker, where “the deadlines come fast and furious.” But the results are rewarding.

“It’s been all the emotions, from intimidating to exciting,” said Maj. Stacie Shafran, a public affairs officer and recent Project Mercury graduate whose team studied renewable energy in the Pacific.

Working with a diverse group refined her approach to figuring out complex challenges and pushing new ideas, Shafran said. Her team developed Rays to Jet Power, a system which uses roll-out fabric solar panels to generate electricity, an improvement over traditional generators which require costly supply chains of diesel fuel.

“One of my teammates is stationed in Guam, where the urgent need for sustainable alternatives was highlighted by the aftermath of Typhoon Mawar in 2023,” Shafran said. “It’s been deeply rewarding to contribute to a solution that addresses these critical challenges.”

At the end of the course, students pitch an idea to expert stakeholders. While the point of Project Mercury is not to create gadgets, the cohorts have developed a long list of impressive solutions. One group created a suite of apps allowing interagency first responders to quickly share information while responding to a crisis, which helped during Hurricane Ian in 2022 and the Hawaii wildfires in 2023, Eagle said. Another group inspired Morpheus, an innovation cell within the Air Force Chief of Staff’s Strategic Studies Group.

Besides problem-solving skills, Project Mercury also builds “a common language about innovation” among a diverse group of service members, Marshall said.

“To have those skills and that common language, that’s foundational to all the other changes,” he explained. “I think we’ll see these Airmen be open to new ideas and be able to implement them as they take on senior rank.”

Graduates receive a Professional Innovator certificate from the University of Michigan’s College of Engineering. A 90-day crash course is not enough to keep Project Mercury skills sharp forever, though, said Janson. That is part of the reason why she, Marshall, and many other participants return to the program as coaches for future cohorts. Janson found herself using the skills she developed as a student and ingrained as a coach in her current job helping NATO prepare for 2030.

“You’re just seeing some people’s brains break: like how do you even begin to address this?” she said. “I am not remotely worried by a large, ambiguous project, because I know exactly how to start addressing it.”

Like other Air University professional military education offerings, Project Mercury is open to all Airmen and Guardians along with a limited number of service members and civilians at all ranks from all branches, other government agencies, and allied or partner militaries. The openness makes Project Mercury among the most diverse “classrooms” in the Defense Department, said Jim Dryjanski, the Air University Director of Project Mercury.

Project Mercury’s reach has grown to include partners and allies, including the Republic of Singapore Air Force, the National Guard, the NATO Innovation Hub, and NATO Allied Transformation Command. In late June, NATO is hosting a Project Mercury Innovator Workshop in Warsaw, Poland, called “Innovators on the Eastern Flank,” further expanding the network.

“It’s really about making you a better leader, in some ways a better person, and taking the world around you as a place where you are empowered to make change,” Janson said. “I think we need that today, when sometimes people can really feel un-empowered, to know that if you can just apply yourself and use the right tools, you can make change around you.”