Reexamining the record, there is now conclusive evidence that credit for the historic shootdown should go to a single Airman.

In the 1962 classic Western “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” Jimmy Stewart plays a U.S. senator whose life and legend are largely built on his having shot and killed a notorious bully, Liberty Valance, played by Lee Marvin. Only later does it come clear that it was not Stewart’s character, but a small-time rancher played by John Wayne who fired the deadly round. The wrong man got the credit—and the fame and fortune that went with it.

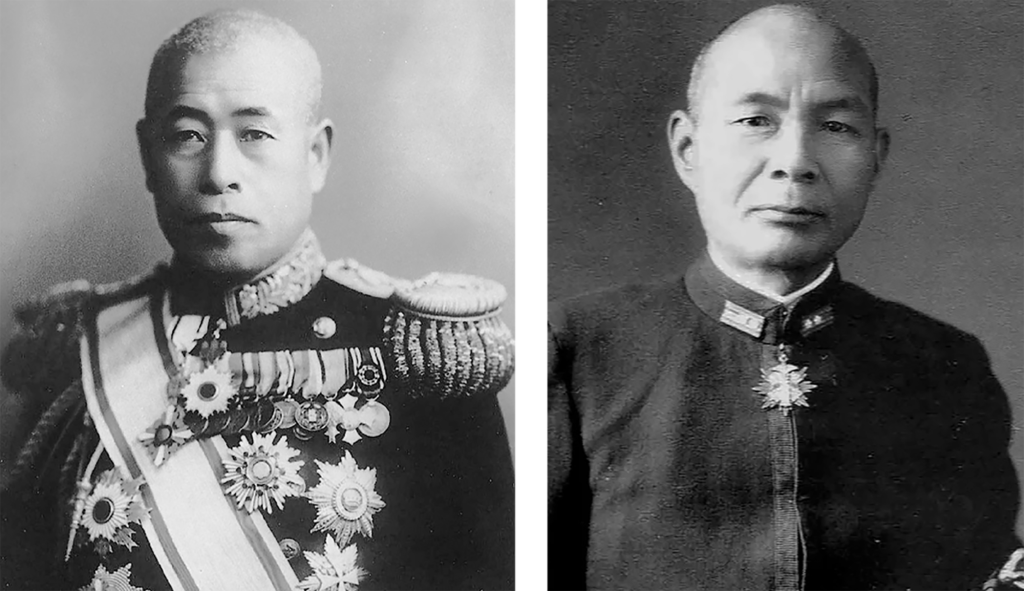

The shootdown of Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto provides a similar case study. Yamamoto was a star in the Japanese navy, a Harvard-educated visionary who championed aircraft carriers over battleships and conceived the idea to bomb the U.S. fleet at rest in Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Capt. Thomas G. Lanphier Jr. claimed to have shot down Yamamoto’s plane, killing him in the process, but the evidence indicates it was not Lanphier, but his wingman, Rex Barber, who deserved the credit.

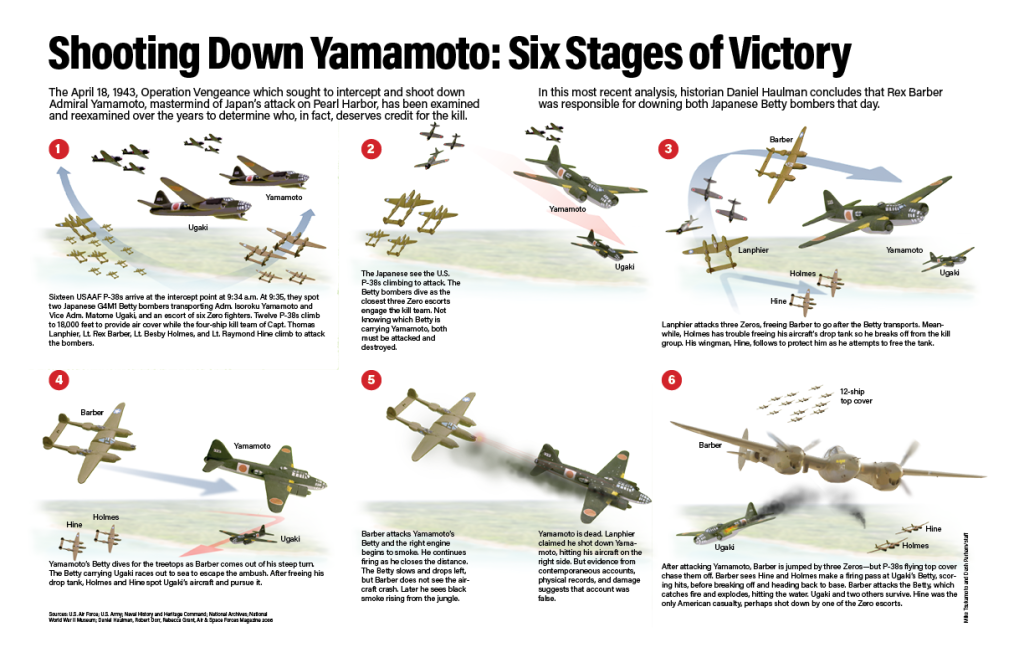

Approaching Bougainville, the P-38s encounter two bombers and six escorts, not one bomber and escorts as expected. Unsure which carried Yamamoto, they had to attempt to destroy both.

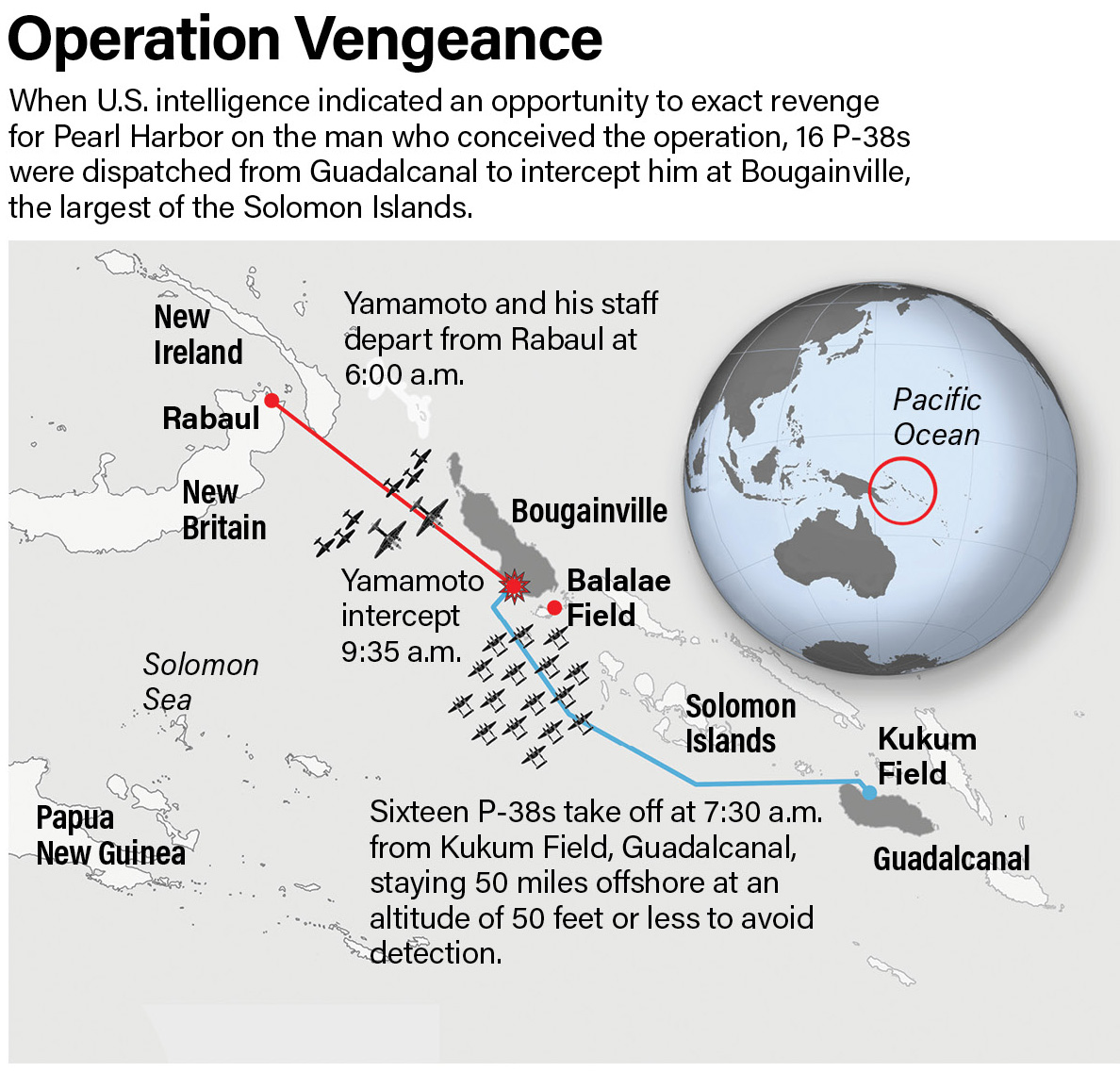

The mission to shoot down Yamamoto was launched on April 18, 1943, exactly one year after the Doolittle Raid on Japan. It was also the anniversary of Paul Revere’s famous midnight ride in 1775. American code-breakers in the Pacific theater had discovered that Yamamoto, who had planned the Pearl Harbor and Midway attacks in 1941 and 1942, was scheduled to fly to the vicinity of Bougainville in the Solomon Islands. The Army Air Forces had P-38 Lightnings at Guadalcanal with auxiliary fuel tanks, giving them the range to fly the more than 800 miles round trip to Bougainville, and therefore the ability to target Yamamoto.

Maj. John Mitchell commanded the mission. He planned to launch 18 P-38s from Guadalcanal, 14 to fly top cover for an attack flight of four. Two of the planes aborted, leaving 16 Lightnings on the raid. They flew low, in radio silence, changing course several times to avoid flying over Japanese island bases in the Solomons. When the P-38s approached Bougainville, 12 of them climbed to provide top cover for the four-plane attack flight under Lanphier. The other three pilots were Lt. Rex T. Barber, Lanphier’s wingman, Lt. Besby F. Holmes, and Lt. Raymond K. Hine.

Approaching Bougainville, the P-38s encountered the Yamamoto flight. Meticulous planning, along with Yamamoto’s fulfilled reputation for punctuality, benefited the raiders. They had expected to see one Japanese G4M1 Betty bomber with Yamamoto aboard, escorted by six fighters. Instead, the six fighters were escorting two Betty bombers, one carrying Yamamoto and the other some of his staff. Unsure which one carried the admiral, the American attackers had to attempt to destroy both Japanese bombers.

Lanphier flew toward one of the Betty bombers but first had to engage in a dogfight with the escorting Zeroes before he could attempt to shoot it down. He reported shooting down a Zero before circling back. Lanphier’s encounter with the Zeroes allowed Barber to chase one of the bombers, firing at it from behind and scoring several hits. Barber momentarily lost sight of the bomber, then spotted a crash and assumed he had shot the plane down over the island. But after Barber scored hits on Yamamoto’s bomber, Lanphier saw and attacked it from the right side, claiming to have shot off the plane’s right wing before it crashed. What he witnessed might have actually been the result of Barber’s having previously fired on the plane.

Holmes and Hine, the other two members of the attack flight, had been delayed. Holmes turned violently to shake off a fuel tank, and his wingman Hine had followed him. Coming into the fight, they concentrated on the other Betty bomber, which was heading out to sea. They fired at the plane and soon after Barber joined them in pursuit. Barber then finished off the second Japanese bomber.

Only three of the members of the four-plane attack flight returned to Guadalcanal’s Henderson Field. Hine was lost, perhaps shot down by one of the escorts on the way back. Arriving at base, Lanphier, Barber, and Holmes all claimed to have shot at Betty bombers on the mission. Lanphier claimed to have shot down one that crashed on the island. Holmes claimed to have shot down one that crashed in the sea near the island. Barber claimed to have shot at both bombers before they went down. Apparently, they had no gun camera footage to bolster their claims. The gun cameras must have been left at Guadalcanal to save weight on the extremely long interception mission.

At first, intelligence evaluators thought that instead of two Japanese bombers over western Bougainville that day, there might have been three. They credited Lanphier, Barber, and Holmes with one bomber kill each. But Lanphier continued to claim that he got the bomber that Yamamoto was on, though Barber noted that no one knew which of the bombers carried Yamamoto. It seemed possible that Barber might have gotten him instead, since two bombers apparently had gone down over the island. Early publications seemed to favor Lanphier’s version of events.

In the 1970s, USAF historians gathered documents to produce a listing of Army Air Forces aerial victories during World War II, attempting to assign credit consistently for all theaters. USAF Historical Study No. 85, published in 1978, assigned official credit for shooting down Yamamoto’s plane to both Lanphier and Barber. By then, Japanese evidence confirmed that there were only two Betty bombers in the Yamamoto flight, that one that went down on the island while the other went down in the sea. Reasoning that since Lanphier and Barber both claimed to have shot at a bomber that went down over the island, and that Yamamoto was on that plane, they should share credit for shooting down Yamamoto. The record was revised to give each pilot half a credit. The historians also decided to split the credit for shooting down the other bomber between Holmes and Barber.

When Lanphier discovered that the Air Force was officially splitting credit for shooting down Yamamoto between him and Barber, he was upset. Lanphier demanded that the Air Force reconsider the case, and award him full credit. In March 1985, the Air Force reopened the matter, calling together a six-person review board to reconsider the case of who shot down Yamamoto. The six members of the review board were Lt. Col. Frederick E. Zoes, Lt. Col. Donald B. Dodd, Maj. Lester A. Sliter, Col. Benjamin B. Williams, R. Cargill Hall, and myself, Daniel L. Haulman. The board’s members were told to consider only the original evidence and no new evidence. This time the board concluded the evidence showed that both Lanphier and Barber had shot and hit Yamamoto’s plane, at different times, and that therefore credit should remain split between them. Once again, Lanphier and Barber each received half credit for shooting down Yamamoto’s plane. That decision was upheld.

Lanphier died two years later, in 1987. By then, Rex Barber and his supporters had determined that new evidence supported Barber’s claim to the full credit. An examination of the wreckage site on Bougainville showed Lanphier could not have shot off the right wing of Yamamoto’s plane while it was still in the air, as he had claimed, because while the right wing had come off the wrecked plane, it was laying right next to the fuselage, probably ripped off when the plane crashed into the trees on its descent. If Lanphier had shot off the wing, it would have ended up much farther away. Their examination cast doubt on other aspects of Lanphier’s account. After dealing with at least one of the escorting Zeroes, Lanphier had little time to catch up with the Yamamoto bomber and get it in his range. And if he were shooting from the side of a rapidly moving target, he would have had very little chance to hit his target even if it was in range. The wreckage also showed that Yamamoto’s bomber had been shot at from behind, aligning with Barber’s account, as he was the one who claimed to have shot down the bomber from behind.

Additional new evidence bolstered Barber’s case. The Japanese autopsy report on Yamamoto showed the admiral had been killed from bullets fired from his rear, again consistent with Barber’s account. A Japanese fighter pilot escorting the plane also noted that Yamamoto’s bomber had been shot at from behind. All the new evidence supported Barber’s version of the kill, and none supported Lanphier’s account.

Many of those following the controversy wondered if Lanphier had knowingly claimed the kill due his wingman.

Of course, by then Lanphier was no longer among the living. In 1991, the Air Force called a new Board for the Correction of Military Records to review the case of who shot down Yamamoto. This time, the board faced fewer restrictions, and was able to review evidence not available to previous researchers. The result was split. While none of the members concluded that Lanphier alone had shot down Yamamoto, the new board remained divided on whether the credit should be shared between Lanphier and Barber, or whether Barber should get sole credit for the kill. Deadlocked, the matter was forwarded to then-Secretary of the Air Force Donald B. Rice, who ruled in 1993 that the credit should remain split between Lanphier and Barber.

Even then, the controversy continued. Barber and his supporters challenged Rice’s authority to make the final decision in a lawsuit, filing suit in federal court. The court found in 1996 that the Secretary of the Air Force did have the authority to settle the issue, effectively leaving Rice’s decision in place and credit for the shootdown evenly split between Lanphier and Barber.

Now outside organizations took up the cause. The American Fighter Aces Association and the Veterans of Foreign Wars, both independent nonprofit entities, objected.

Having been a member of the 1985 official USAF panel to look at the Yamamoto kill case, and having reviewed new evidence since, I have become convinced that, despite the panel decision and the subsequent Rice decision, credit for shooting down Yamamoto’s plane really should go to Rex Barber. Thomas Lanphier does not deserve credit for shooting down Yamamoto. The original evidence suggested that since only one of the Japanese Betty bombers went down on Bougainville, and that both Lanphier and Barber had claimed to have shot at a Japanese Betty bomber that crashed on the island, both should have credit. New evidence shows that Barber was the only American P-38 pilot to have hit the plane. Lanphier was too far away, and his angle would have not allowed him to destroy such a fast-moving target from the side.

Even if he had been close enough to the bomber for a few of his bullets to have hit it, they would have done little damage, and certainly not enough to take off a wing. The wreckage evidence and the Japanese autopsy evidence showed that Yamamoto’s plane was hit from the rear, which is consistent with Barber’s version of events. Barber alone should have credit for having shot down Admiral Yamamoto’s plane, which deprived the Japanese of one of their most important military leaders. If Barber was the only American pilot to have shot down Yamamoto, he deserved a Medal of Honor for doing so. At least that is what Maj. John Mitchell, commander of the mission, thought.

LEARN MORE

Daniel L. Haulman was head of the organizational histories branch of the Air Force Historical Research Agency and participated in several reviews of Operation Vengeance. The author of several books, including “Killing Yamamoto,” published in 2015. His conclusions here, based on the full body of evidence, differ from those in that book.

For this article, the following primary sources were consulted:

• XIII Fighter Command Debriefing of April 18, 1943, mission, subject: Fighter Interception. To Commanding General, USAFISPA [U.S. Army Forces in the South Pacific Area], from Army Intelligence.

• 339th Fighter Squadron History, Oct. 30, 1942-Dec. 31, 1943, by historical officer Kim Darragh.

• Assistant Chief of Air Staff Intelligence Digest of June 15, 1943 (extract from Air Command Solomon Islands Intelligence Bulletin for April 18, 1943).

• Interviews with Maj. John W. Mitchell and Capt. Thomas G. Lanphier Jr. by Assistant Chief of Air Staff, Intelligence, June 15, 1943.

• 1985 Victory Credit Board of Review, March 22, 1985.

• Daily Mission Reports, XIII Fighter Command, April-June 1943.

• Corporal Tommie Moore, Story of 339th Fighter Squadron, Public Relations Office, Thirteenth Air Force, Report of Action, April 18, 1943.

• 70th Fighter Squadron History, Jan. 1-June 30, 1943.

• Operations Letters, Letter: Harmon to Arnold, May 1, 1943.

• History of the Thirteenth Air Force, March-October 1943.

Books about the Yamamoto shootdown include:

• John Deane Potter, “Yamamoto: The Man Who Menaced America” (New York: The Viking Press, 1965). Gave credit to Lanphier.

• Burke Davis, “Get Yamamoto ” (New York: Random House, 1969). Gave credit to Lanphier and Barber.

• Hiroyaki Agawa, “The Reluctant Admiral: Yamamoto and the Imperial Navy ” (Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1979). Inconclusive on Lanphier or Barber.

• Edwin P. Hoyt, “The Glory of the Solomons ” (New York: Stin and Day, 1983). Gave credit to Lanphier.

• Ronald H. Spector, “Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan ” (New York: The Free Press, 1985). Gave credit to Lanphier.

• R. Cargill Hall, “Lightning Over Bougainville: The Yamamoto Mission Reconsidered” (Washington and London: Smithsonian Institution Press, 1991). Gave credit to Lanphier and Barber.

• Carroll V. Glines, “Attack on Yamamoto ” (Atglen, Pa.: Schiffer Military History, 1993). Gave credit to Barber.

• Donald A. Davis, “Lightning Strike” (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2005). Gave credit to Barber.

• Daniel Haulman, “Killing Yamamoto: The American Raid that Avenged Pearl Harbor ” (Montgomery, Ala.: NewSouth Books, 2015).

• Dan Hampton, “Operation Vengeance” (New York: HarperCollins, 2020). Gave credit to Barber.

• Dick Lehr, “Dead Reckoning” (New York: HarperCollins, 2020). Gave credit to Barber.