ORLANDO, Fla.—For decades, the Space Force and the Air Force before it have had a tried-and-true method: massive, costly satellites are sent into orbit by launches that have been planned for months. Once there, those satellites mostly stay put in their orbits, preserving as much fuel as possible because, once that fuel is gone, the spacecraft’s service life is over.

Now the Space Force is rethinking that formula, investing to build large constellations of much smaller satellites. “Resilience” is the priority. But USSF and industry leaders are also adding another watchword to their operations: “dynamic.”

Whether delivering satellites into orbit in a matter of days, maneuvering satellites more actively, or refueling them in orbit, the Space Force is reshaping its operational concepts to better operate in an increasingly complex and unpredictable domain.

“We know speed to orbit and we know resiliency on orbit are fundamental principles that we want to adhere to,” Chief of Space Operations Gen. B. Chance Saltzman told reporters at the Space Force Association’s inaugural Spacepower Conference. “Now how do we take advantage of it, if we were to have it? That’s the work left to be done.”

Retired USSF Lt. Gen. John E. Shaw began articulating the concept of “dynamic space operations” earlier this year when he was still vice commander of U.S. Space Command. Now Saltzman is going further, describing it as “almost continuous maneuvering, so that the satellites from any one radar shot looks like it’s maneuvering and it’s just kind of constantly changing its orbit as it goes through—preserving mission but changing its orbit.”

Such maneuvering is not possible with most existing USSF satellites, which only carry enough propellant for “station keeping” and cannot be refueled. For now, Saltzman said, dynamic operations is only in the “good idea phase.”

But more development is ahead. “Our futurists, our people that are considering operational concepts that are several years down the road, this is one of the things that they’re factoring in,” he said.

This is all driven by threat, military and industry space experts say.

“When we listen to the demand signal from U.S. Space Command and the need to do dynamic space operations, the need to be able to maneuver without regret, that capability is now coming from us,” said Brig. Gen. Kristin L. Panzenhagen, program executive officer for the Assured Access to Space directorate. “It shouldn’t be a surprise or anything—one of the principles of warfare is maneuver. So now here we are in the space domain with a need to do that.”

The need being articulated by SPACECOM is twofold, added Kelly D. Hammett, director of the Space Rapid Capabilities Office.

“If somebody is sending a co-orbital [anti-satellite missile] at you, you can actually run away,” Hammett told reporters. “You can move. You can respond and do things. And that’s on that side of the house. … The other piece is maneuver for space warfighting. Our commercial systems are watching what the Chinese in particular are doing on orbit right now. They’re practicing tactics and techniques. They’re maneuvering, they’re showing how they would ingress on potential targets. They’re completing robotic maneuvers and rendezvous and [proximity] ops. How will we have capabilities to address those threats and potentially fight the space war fight?”

A few days after Hammett’s remarks, the Chinese launched their uncrewed Shenlong space plane, which reportedly deployed six mysterious objects into orbit. Officials have previously spoken of a Chinese satellite with a “grappling arm” that could grab other nearby satellites, and a Russian “nesting doll” satellite that deployed multiple spacecraft after reaching orbit.

Being able to respond to these threats will require what Saltzman and other leaders call “regret-free maneuver,” or the ability to move a satellite without worrying too much about the precious fuel burned to do so.

One possibility is refuelable satellites—Hammett suggested the Space RCO is now only building satellites that can be refueled. Saltzman also suggested it could mean equipping small satellites with large amounts of fuel. On Dec. 11, the Assured Access to Space directorate issued a request for information from industry on ideas of refueling and mobility.

“One thing we really need to understand fully is the concept of operations and the demand signals,” Panzenhagen said. “So we appreciate from the program office side, we’ve had a lot of tabletop exercises, really trying to understand what those requirements are. We’ve got now satellite program offices that are starting to build for refueling capability. For the industry side of the house, what we really need to understand is one, the state of technology and I think we’re getting a much better understanding of that, and the RFI … will continue to aid in that understanding. But we also really need to understand the business case.”

There is plenty of interest from industry for developing “space tankers.” Startup Orbit Fab has designed a standard port for satellites to dock into its “gas stations in space,” with the first refueler scheduled to go up in geosynchronous orbit in 2025. Northrop Grumman also offers in-orbit refueling through its subsidiary, SpaceLogisitics, and launch provider Blue Origin recently unveiled a new spacecraft, Blue Ring, “focused on providing in-space logistics and delivery,” including fuel.

“The Blue Ring is going to offer a lot of on-orbit capability: several kilometers per second in Delta V, a hybrid propulsion solution, and thousands of kilograms of mass toward the capability and the ability to stay on orbit, the ability to maneuver on orbit, the ability to maneuver between orbits and beyond GEO into cislunar,” said Blue Origin vice president of government sales Lars Hoffman. “These kinds of capabilities that we’re talking about here are going to complicate the calculus of our adversary. It’s going to challenge their thinking. And it’s opening up all sorts of new ideas for our Guardians to be thinking about, ‘What would I do with that?’”

Refueling isn’t the only major change coming in how the Space Force responds to new threats and requirements. During his keynote address, Saltzman took several minutes to stress how important the “Victus Nox” mission was, and how significant it was to prove USSF and its industry partners can build a satellite in less than a year and prep it for launch in a matter of days .

The “tactically responsive space” (TacRS) mission helped advance the Space Force’s drive to be both fast and flexible.

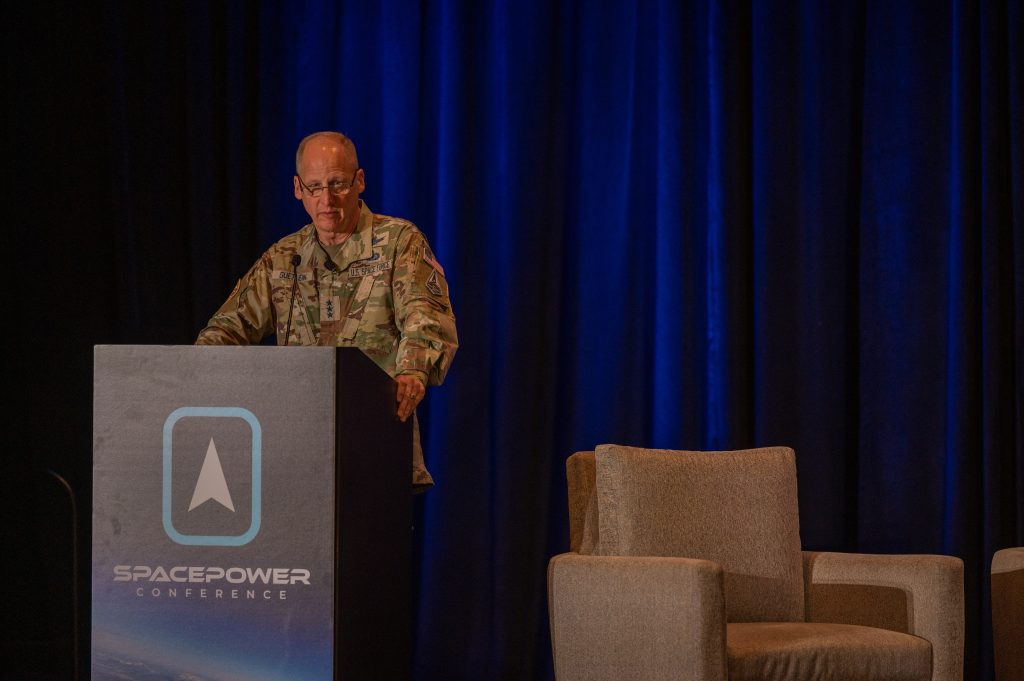

“It’s about taking advantage of capabilities on the ground, mating them, and getting them on orbit in new and innovative ways,” said SSC commander Lt. Gen. Michael Geutlein.

More TacRS missions are coming as the Space Force builds on its capacity to respond “under attack,” said Geutlein.

Becoming more dynamic and responsive will come with potential challenges, though. Hammett noted that command and control in space is poised to become vastly more complex if satellites can move rapidly—especially given the catastrophic effects a collision in space can have.

“When you think about … all the systems that SDA, SSC, and we are building, there are a lot of things coming in the next three years, and now they can all maneuver,” Hammett said. “Now they all need to maneuver to respond to threats. How do you synchronize those? How do you tell everything where to go and when to go there? You need more capability to C2 those things.”

Saltzman said the change in approach literally changes “how you do space domain awareness: Keeping track of a dynamically moving object is fundamentally different than anything we do now.” That poses challenges to USSF, but even greater challenges to potential adversaries.

Now, as USSF celebrates its fourth birthday and heads into its fifth year, Saltzman is focused on maintaining that momentum.

“Being able to put something on orbit in a matter of days, like we showed, the ability then to protect the satellite through dynamic maneuvering: How do these operational concepts support the theory of success?” Saltzman asked. “How do they help us either create resiliency, do responsible counterspace campaigning? How does it help us avoid operational surprise? … What are the potential possibilities for how all this fits together? And kind of the easy answer is I don’t know yet. We’re asking all those questions.”