The Air Force is bringing back an old radar technology to detect cruise missiles, but experts warn it must be deployed sooner alongside a comprehensive network of missile detecting and defeating systems to be effective.

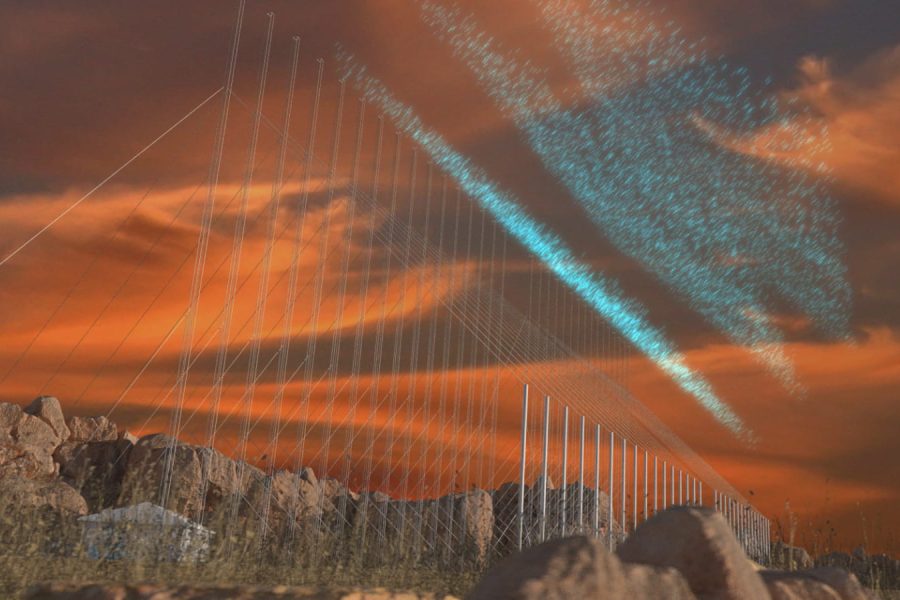

Over-the-horizon radar (OTHR) was first developed during the Cold War to detect Soviet bomber attacks from thousands of miles away, according to the Federation of American Scientists. Most radars are limited by the curvature of the Earth, allowing potential threats to fly ‘under the radar’ without being detected. But OTHR bounces high-frequency radio signals off the ionosphere, which starts about 50 miles above the Earth’s surface. The descending signals rebound off objects below, then back off the ionosphere before returning to the receiver. OTHR provides early warning of incoming threats more than 1,000 miles away, much farther than conventional radar systems.

A plan to build OTHR in Alaska was abandoned after the Cold War ended, but the emerging threat of cruise missiles from possible adversaries such as China and Russia has brought the system back into focus.

Unlike ballistic missiles, which follow predictable flight paths, cruise missiles can maneuver unpredictably at low altitudes, be launched from a range of platforms, and may reach hypersonic speeds as technology develops.

The Air Force plans to build four OTHRs for North American Aerospace Defense Command/U.S. Northern Command (NORAD/NORTHCOM), but the process is in the early stages; on Aug. 21, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers released a sources sought notice for building “two remote sites in the North-West United States.”

When they do go up, the new systems could be more advanced than their Cold War predecessors. RTX, the company recently known as Raytheon Technologies, is developing a “next-generation” OTHR that includes advanced transmitters, digital receivers, and a more compact receiver array. A press release about the system notes “adaptive signal processing and advanced digital beamforming,” which should mitigate signal clutter, reduce processing requirements, and improve target detection.

“The next generation that we need for this particular mission set increases the sensitivity of the radar significantly,” Paul Ferraro, president of air power at Raytheon, the defense business unit for RTX, told reporters at an Aug. 31 event.

RTX is no stranger to OTHR systems, having developed three in the 1990s that the Navy uses as surveillance assets for drug trafficking interdiction, Ferraro said. Even so, OTHR is not effective without a larger system to act on the information it provides. Though OTHR can see a great distance, it does not have the same fidelity as other radars that can produce “engagement quality tracks,” Ferraro said.

That means once OTHR detects a threat, it must be able to share information quickly across vast distances so other radars can hone in on the object, then send that information to planners at NORAD/NORTHCOM.

“It is critically important that all of this data is presented to an operator in total, because that gives them the most comprehensive picture of the threat space that they’re trying to defend against,” said Ferraro, echoing what Air Force Gen. Glen D. VanHerck, the head of NORAD/NORTHCOM, told lawmakers in May.

“There has to be domain awareness between the over-the-horizon radars that link the data from there to an end-game effector,” the general said. “We need to look more broadly at the rest of the infrastructures, the radar as well, and ensure the data from those systems is incorporated in an integrated air and missile defense system that can lead to effectors.”

Experts and officials warn that there are many holes in today’s air and missile defense system. The North Warning System, a network of 47 radar stations monitoring the air space over the Canadian Arctic and Alaska, is based on outdated technology first developed in the 1970s, wrote Dr. Caitlin Lee, senior fellow at the Mitchell Institute, in a June paper. The technology may become less effective as China and Russia develop stealthier cruise missiles that could be launched from an array of platforms. VanHerck himself described the system as “a solid fence shrinking to a picket fence.”

Other gaps in the fence are formed by a scarcity of Arctic air- and space-based surveillance assets; a lack of Arctic infrastructure like runways and fuel storage; difficulty identifying airborne objects; and inefficient information-sharing systems, Lee wrote. Fixing it will require a modernized, holistic “missile defeat” system that involves robust detection and tracking mechanisms and a range of interception tools including passive, kinetic, and non-kinetic capabilities, such as cyber warfare, directed energy, and electronic attacks, Lee said.

There are signs of progress. In March, President Joe Biden and Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau laid out a NORAD modernization plan pledging two next-generation OTHR systems “covering the Arctic and Polar approaches, the first by 2028.” The plan also commits to building northern forward operating locations for fifth-generation aircraft and mobility/refueling aircraft. It also seeks to improve “the cybersecurity and resiliency of our critical infrastructure.”

Canada plans to build two OTHR systems, while the Air Force is responsible for funding another four, but the whole set will not be operational until 2031. That is not fast enough, wrote Lee, who called for investing $55 million on NORAD’s unfunded priority list into accelerating OTHR to 2027. She also urged investing about $211 million to amplify the North Warning System with nine advanced mobile Three Dimensional Expeditionary Long Range Radars.

“Arctic domain awareness and information dominance should be a top DOD priority now, not in a decade or more, to shore up cruise missile defense of the homeland,” she wrote.