DAYTON, Ohio—The engines for the hyper-secret Next Generation Air Dominance fighter will be a different size than the adaptive engines developed for an F-35 upgrade, but many of the technologies will “port over” to the new powerplant, the Air Force’s propulsion czar told reporters Aug. 1.

John R. Sneden, propulsion director for the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center, also said the Air Force plans to keep both GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney in the prototyping phase for the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) engine which will power NGAD, after the two engine-makers participated in the Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) meant for the F-35.

“The engines that we developed for AETP were sized for the F-35,” said Sneden. “Those that will go into NGAD are different engines; they will be differently-sized engines. But the technology baseline … is essentially the same.”

Asked later if the NGAP engines will be larger than the AETP ones, Sneden said through a spokesperson that, “as with any new weapon system development, the NGAP propulsion systems will be sized appropriately to meet thrust, weight, and other integration requirements.”

There has been a steady increase in the size of fighter powerplants from the F100 of the 1970s to the the F135 of the 2000s—the F100’s fan diameter was just 34.8 inches, compared to 43 inches for F135. AETP is even larger, at 46 inches.

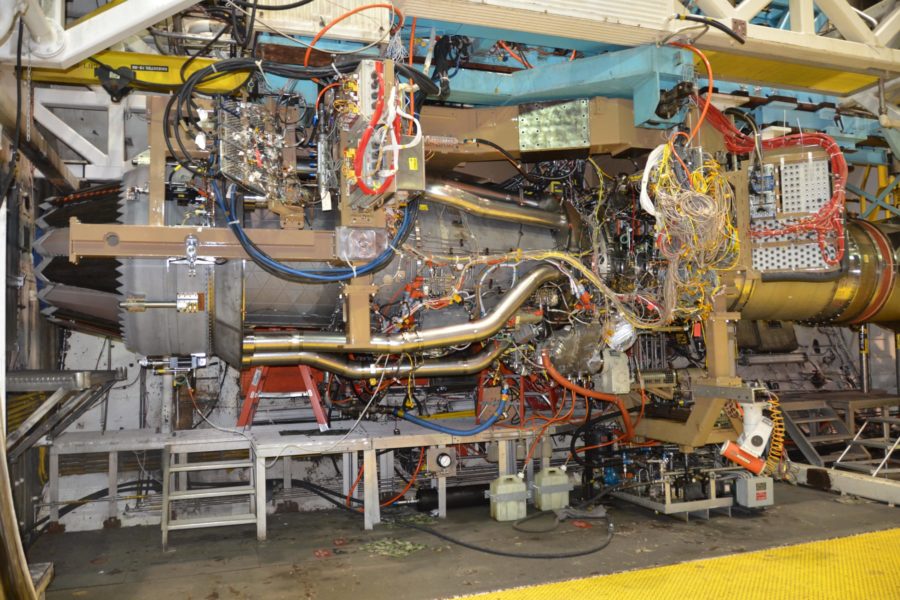

The AETP engines—Pratt’s XA100 and GE’s XA101—were developed with the F-35 in mind, but the Pentagon opted to forego the program in its fiscal year 2024 budget request. While they fit in the F-35A, the engines would need a redesign to fit the carrier-capable F-35C and short takeoff/vertical landing F-35B. Instead, the services have opted for the F135 Engine Core Upgrade offered by Pratt & Whitney. The ECU can apply to all F-35 variants.

But while the AETP engines will not be used in the F-35, Sneden argued the technology they helped develop is “critical” to NGAD and necessary for ensuring the U.S. maintains its advantage in propulsion over China.

According to officials, the AETP engines offer double-digit gains in both specific thrust and fuel efficiency. Sneden said the program also developed next technologies like advanced materials and composites, ceramic matrix materials, thermal management improvements, and additive manufacturing which collectively will deliver the increased capabilities the NGAD will need.

As a result, those advancements won’t be “lost … or wasted,” he said. “It just gets incorporated into a design that’s critical for the NGAP system.”

While the Air Force has said it is ready to move on from AETP, some lawmakers are not—the House approved funding to resurrect the program in its version of the National Defense Authorization Act, while the Senate did not. Both chambers agreed to fund the Air Force’s request of nearly $600 million for NGAP.

Asked if AETP could be put on hold and developed for the F-35 at some future point, Sneden demurred.

“Our current focus right now is just to get the technology to a logical transition point” for NGAP, he said.

In order to have both the best choice for NGAP and to sustain what he has described for two years now as a fragile propulsion industrial base, both GE Aerospace and Pratt & Whitney will likely be carried into a prototyping phase, he said.

“With the way we’re funded, we think we can carry both through prototype, and both are leaning in fully,” Sneden said. “And so then we’ll [contract for] the prototype” and carry out a test and evaluation program. That could continue until a winner is chosen, unless one is an early and clearly superior performer, he said.

“We still have that opportunity to do a downselect if we start seeing … huge separation between the two,” he said. Previous plans had called for choosing one company to develop NGAP based on proposals alone, without a competitive prototyping effort.

While Sneden would not provide a timeline for NGAP, he did say the program is undergoing “detailed design activities right now. And within the next couple of years, we’ll be moving into prototyping testing.”

Asked why traditional airframers Boeing, Lockheed Martin and Northrop Grumman received NGAD propulsion contracts last year—in addition to awards to GE and Pratt—Sneden said it was to ensure “that there was an interface methodology between the airframe company and the propulsion company.”

Northrop recently said it would not bid on NGAD.

The Air Force will settle on one design that will fit any of the NGAD designs, Sneden said. After selecting one engine and one air frame, “there could be some optimization of that system and that particular design.” But all the companies are observing “the propulsion constraints that we’ve studied, and evaluated, and provided to each,” he added.

Industrial Base

Given the limited number of contractors working in advanced propulsion, Sneden said his team is focused on maintaining the industrial base and bolstering U.S. advantages in the space. That means “competition, wherever possible, and continuing to fund both vendors for as long as we possibly can.”

NGAP in particular is critical to the U.S., Sneden argued, because of advancements China is making in the arena that threaten U.S. dominance. It’s a warning he issued last year as well.

“Through intellectual property theft, working with Russia, and frankly, just their own development, activity and budget … they’ve made significant leaps and bounds over this last roughly eight-plus years,” he observed.

With greater investment in propulsion, China has closed the gap to the U.S., Sneden said.

“Our focus is not letting them do that,” and he said the adaptive engine technology “is the right way, and incorporating into the NGAD system is our assurance of long-term air dominance and propulsion superiority.”

Surveying the state of the American engine industrial base, Sneden said the current process takes too long and cannot respond to threats fast enough.

“In fairness to my industry partners, they haven’t really been challenged or incentivized through the majority of our contracts,” Sneden said. “The sole-source nature of our enterprise also exacerbates that same problem by removing some of those competitive forces that drive innovation, speed and cost control.”