In just 10 seconds, a normal training mission became a nearly fatal accident when an F-35 fighter jet crashed while landing at Hill Air Force Base, Utah, on Oct. 19, 2022. An investigation published July 27 found the crash was caused by a glitch in the aircraft software system which occurred after the pilot, who survived with minor injuries after ejecting from the stricken jet, flew too close into the turbulence left by the wake of the F-35 ahead of him.

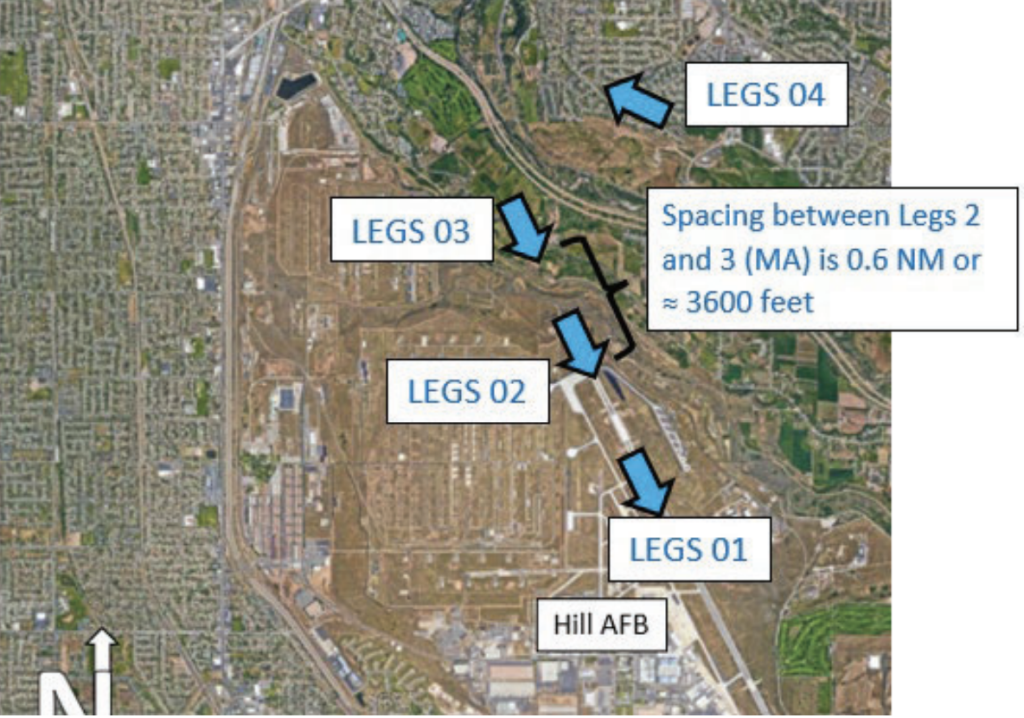

According to the investigation, the mishap aircraft was one of a formation of four F-35s returning from a training event over the Utah Test and Training Range that evening. Due to a local windspeed of five knots, the base control tower had declared that “wake turbulence procedures were in effect,” which means aircraft coming in to land had to trail at least 9,000 feet behind the aircraft in front of them, rather than the usual 3,000 feet.

The investigation added that encountering wake turbulence is very common in aviation and usually harmless, but not during the landing phase, where unexpected rolling motions can be disastrous so close to the ground. Investigators said the pilots in the formation should have known wake turbulence procedures were in effect because the control tower noted windspeed of five knots over the runway.

However, neither the mishap pilot nor one of the other pilots were aware wake turbulence procedures were in effect, and the mishap pilot planned to land with the usual minimum 3,000 feet of separation, though the actual distance in this event was around 3,600 feet.

With landing gear down on final approach, the mishap pilot felt some rumbling due to the wake turbulence of the F-35 ahead of him. He flew through the disturbed air for about three seconds, which threw off the jet’s air data system (ADS).

The ADS is made up of sensors that collect information from outside the aircraft so that the aircraft computers can calculate the minute control adjustments needed to keep flying. In this case, the disturbed air made the ADS occasionally stop listening to data coming in from sensors on the right side of the aircraft, and stop listening to data from the left side altogether.

Each time the ADS switched between those primary sensors and backup sources for gauging flight conditions, the further its assessments drifted from actual flight conditions. The poor assessments led to the ADS calculating incorrect flight adjustments, and the pilot found the system disregarded his own attempts to get the jet back under control.

The jet “looked like a totally normal F-35 before obviously going out of control,” one F-35 test pilot who saw the mishap from the ground told investigators. “When the oscillations were happening, I did see really large flight control surface movements, stabs, trailing edge flaps, rudders all seem to be moving pretty rapidly like, probably at their rate limits, and huge deflections.”

Air Force jets are often equipped with computers that make minor control adjustments mid-flight, and they usually work without issue. Investigators noted there have been over 600,000 F-35 flight hours “with no known similar incidents of wake turbulence impacting the ADS.”

But on this flight, the F-35 put itself in a position with “virtually no chance of recovering,” the test pilot said. The mishap pilot lit his afterburner to try to regain control, but was unable due to the low altitude and airspeed. With just 200 feet between him and the ground, the pilot ejected and landed safely just outside the airfield fence line. The bulk of the F-35 crashed within airfield boundaries, though parts of the cockpit, canopy, and ejection seat landed just outside the fence. The entire mishap, from the initial rumbling to ejection, took about 10 seconds.

Afterwards, when investigators recreated the events of the crash in a simulator, they found that “each attempt at replicating the mishap sequence resulted in the simulator departing controlled flight.”

In the end, Col. Kevin Lord, president of the accident investigation board, determined the cause of the mishap was the F-35 departing controlled flight due to ADS errors, but the pilot trailing too close to the preceding F-35 was a significant contributing factor.

The F-35 was completely destroyed in the incident, and the Air Force Accident Investigation Board valued the loss at $166.3 million, well above the average cost of an F-35. Air Force policy instructs investigators to determine costs by combining the flyaway cost of an aircraft, non-DOD property damage, and environmental clean-up costs.

“The calculation is based on the cost of the aircraft and any modifications made to the aircraft itself, the payload it was carrying and other factors,” an Air Combat Command spokesperson told Air & Space Forces Magazine. “Specific details regarding the financial breakdown are not releasable due to operational security.”

This was the seventh crash of the Lockheed Martin-made F-35. It was preceded by crashes of two USAF F-35As, two Marine Corps F-35Bs, one U.S. Navy F-35C, one Japan Air Self-Defense Force F-35A, and one Royal Air Force F-35B. Later that December, a Marine Corps F-35B was damaged when its landing gear malfunctioned, causing the nose to the touch the ground. The pilot was unharmed.