50 years after the U.S. ended operations in support of Khmer allies, the last pilot out looks back.

It is an historical footnote now, lost in the larger story of the Vietnam War. As our nation wound down its participation in that conflict, the last chapter of that tragedy played out in Cambodia. There, U.S. air units supported the Cambodian Army until that effort was terminated by congressional action on Aug. 15, 1973.

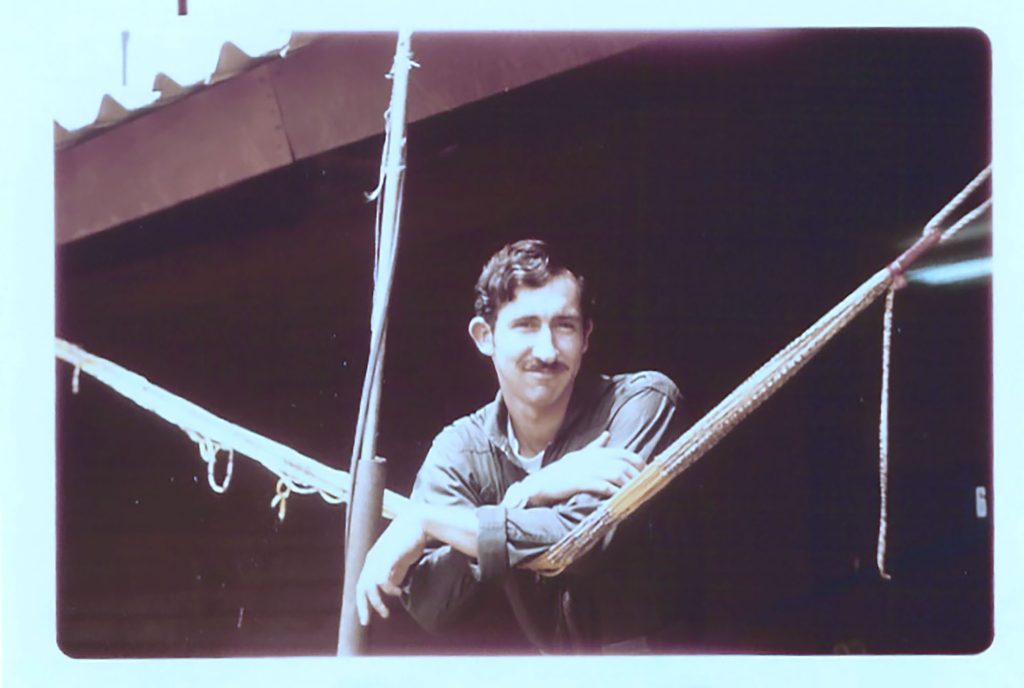

But the memories of those last days have come back to me as we approach the 50th anniversary of date. The memories are strong because I was one of the last pilots to fly those missions on that last day. I was a young captain assigned as a forward air controller or FAC as we called ourselves, and I was a proud member of the 23rd Tactical Air Support Squadron or TASS, located at Nakhon Phanom Air Base in Thailand. We also had a detachment at Ubon Air Base, Thailand.

7th Air Force Commander Gen. John Vogt[This is] the most difficult campaign I’ve had to fight since I have been commander.

Activated in 1966 to work against the growing Ho Chi Minh Trail, in Laos, the 23rd TASS was the one of five TASSes, which at one time had patrolled over the skies of South Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos. But as America withdrew from the conflict, the other proud TASSes had been deactivated and the remaining pilots and navigators had been consolidated in the 23rd. In 1973, it remained as the sole FAC unit in the war, and as the focus of our remaining effort shifted to Cambodia, so did the 23rd. We flew the OV-10 “Bronco” and used the radio call signs of “Nail” and “Rustic.”

I was Nail 25, a moniker I carry proudly to this day.

Throughout that spring and summer, operating out of our detachment site at Ubon Air Base, we flew the length and depth of Cambodia, as a key component of the efforts of 7th Air Force to support our Khmer allies. Gen. John W. Vogt was the 7th commander and recalled that this campaign, because of the convoluted politics of the conflict, was “the most difficult campaign I’ve had to fight since I have been commander of 7th Air Force.” That was saying a lot since he had commanded 7th Air Force the previous year through the Easter Offensive and the Linebacker campaigns.

But we FACs were not aware of all of that. Daily, we flew our assigned missions, We searched for targets in the northeast portion of the country at the southern end of the Ho Chi Minh Trail. We flew into Phnom Penh and worked directly for the Cambodian Army. We provided convoy cover over the critical shipping which came up the Mekong River. We directed airstrikes in support of isolated friendly towns or locations or capped resupply airdrops by C-130 cargo aircraft. And more critically, we ran search and rescue missions for the crews of downed aircraft. The gunners of Cambodia, while not as numerous as those in Laos and North Vietnam, could be just as deadly as their up-country cousins. And sadly, we lost some of our young FACs there; Capt. Joe Gambino and Capt. Dick Gray were killed that summer. Their names as well as the names of F-4, F-111, and Jolly Green crews are up on the Vietnam Wall, near the bottom of panel W-1.

As the congressionally mandated cutoff approached, we did not want to add to that list, and we became very protective of each other. Consequently, on the last day, the squadron commander, Lt. Col. Howie Pierson directed that everybody would fly with two persons per aircraft. He had Capt. Bob Negley with him. He also decided that he and the detachment commander, Lt. Col. Bill Powers, with Capt. Wayne Wroten in his back seat, would fly the last sorties. Additionally, he directed 1st Lt. Charlie Yates and myself to also fly so that if anything happened, he would have “old heads” to handle it. I was all of 25 years old, but had been in the squadron the longest. Charlie had previously done hard duty with the now deactivated 20th TASS in South Vietnam. Charlie had 1st Lt. Woody Baker with him. I had Capt. Bob Haley with me.

Taking off as the last four sorties, each of us flew missions in separate areas. After we had been directed to terminate, we would make sure that everyone else was out ahead of us, and then come home together.

My assigned mission was to work with Army units in contact with enemy troops south of Phnom Penh. Dutifully, I orbited over my troops and directed three flights of F-4s from Ubon Air Base, and A-7s from Korat Air Base, also in Thailand. The ground commander was most appreciative of the support and asked for more. I forwarded his request to the airborne control aircraft above. But instead of more fighters, I was sent the terse message to terminate—for us, the war was over. I told the ground commander. He sadly acknowledged my call.

In the background, I could hear small arms fire. Their war was not over. As I was leaving, he asked me to contact his control center in Phnom Penh and ask them to send Cambodian fighters to support him. I did so, knowing that the pitiful number of small T-28s we left the Cambodian Air Force was grossly inadequate for the job that they would now have to do for themselves.

Then I pointed my trusty OV-10 north for the flight back to Ubon Air Base. Passing over Phnom Penh, I turned on my smoke generator and did loops and rolls over the city—kind of an impromptu air show. Somebody watched because it was later mentioned in Newsweek Magazine.

I could hear the earlier FACs departing to the north ahead of us. One of our young guys, 2nd Lt. Robyn Read had a serious flight instrument problem and needed some help. But 2nd Lt. Jo Slagle joined up with him and led him home. Great work by two of our youngest guys. Otherwise, the flight back to the Thailand border was uneventful; no more problems and nobody behind us. Our mission was complete.

Pierson ordered us to join up as a four-ship formation for the leg to Ubon. We needed to rendezvous and had radios on the aircraft which helped us to do that. But one aircraft had to transmit a signal for the rest of us to home in on. So Charlie Yates pulled out his trusty harmonica and played “Turkey in the Straw” as we guided on his signal. That made the papers too.

As we joined up, Pierson stated that he would lead the flight for the approach and landing. Charlie would be number two. Powers would be number three. Since I had been in the squadron the longest, Pierson gave me the honor of being the last to land. I treasure that kindness to this day.

We tightened up the formation as we flew over the runway. Turning on our smoke generators, we looked like the Thunderbirds coming down initial for the active runway. Each aircraft made a tight break to the left. We landed in sequence, taxied into our squadron area, and shut down our engines. All our other personnel were there to greet us with cold beer and congratulations. The base photographer recorded it all. And our wonderful wing commander, Col. Bill Owens, was there to shake our hands. He even made a speech, something about mission or whatever. We weren’t listening; our feelings were much different. Some were glad it was over. Others were just ready to go home. Some felt empty and wondered what we would do now. But the important thing was that it was over, and we were all safe.

Later, I read that some historian had determined that the last sortie of the war had actually been flown by some A-7 pilot from Korat. What? Those guys were out bombing for us. We watched them leave and then played rear guard for all of them as they flew home.

And of course, our forces did fly in the Mayaguez rescue and the evacuations from Phnom Penh and Saigon in 1975. So even that claim is wrong. It means that our missions that “last” day in Cambodia are but a footnote in the long history of that war.

Yet sometimes footnotes are important. Sometimes that is where the truth resides. The historians would not know. They never flew the missions. We did; and we own the footnotes.