DOD hits the reset button on high school instructor qualifications, opening jobs to more candidates.

A

t Crest High School in Shelby, N.C., retired Master Sgt. John Davis teaches aerospace science and leadership three days a week as the school’s Junior ROTC instructor.

The other two school days, he works on planning, logistics, finances, and paperwork while a substitute—a former full-time instructor—handles the classes.

After school, there’s marksmanship practice on Mondays and Wednesdays until 5 p.m., drill competition practice on Tuesdays, and a flight team meeting on Thursday afternoons after school lets out. On Fridays, team sports or PT assessments provides for physical training, plus a “Raider Challenge” practice—a sort of team obstacle course. Even then, the week’s not over.

Saturdays are often workdays, too. There might be marksmanship, drill, or Raider team competitions at local, regional, and even national levels, or there are monthly orienteering competitions, and sometimes orientation and practice flights with the Civil Air Patrol.

Air Force JROTC Director Col. Johnny McGonigalWe are at an all-time low right now. We have over 160 units of our 870 units total that are unmanned.

If none of that is planned, there are also community service events, such as offering a color guard for a parade or the grand opening for a Walmart in town.

“I don’t sleep much,” Davis says with a laugh.

His wife, Shauna Davis, doesn’t think it’s all that funny. “It’s to his detriment, to his health, to his sleep,” she chimes in. “He’s burning his candle at both ends. But I know he’s doing what he loves, and he wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Maybe he would—if he could. Air Force Junior ROTC programs are to have at least two instructors each, but Crest High has been unable to fill its second slot for two school years. There have been interviews, Davis said, but no hires.

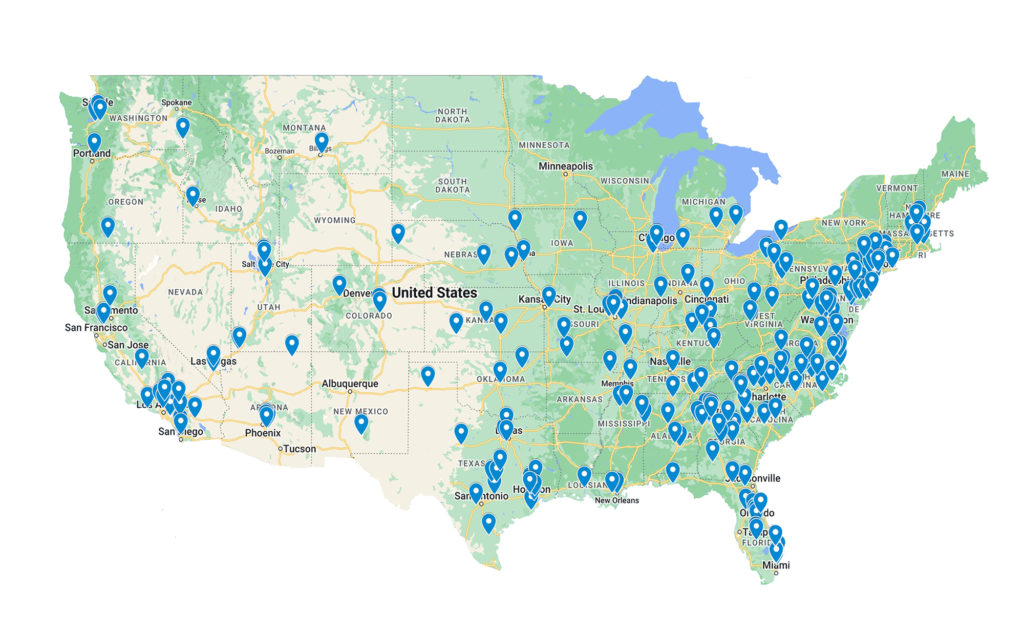

Among the Air Force’s 870 JROTC programs, nearly one in five is short an instructor, said Col. Johnny R. McGonigal, the service’s JROTC director. Some programs have two vacancies.

“We are at all-time lows right now,” McGonigal told Air & Space Forces Magazine in late March. “We have over 160 units of our 870 units total that are undermanned.”

Typically, undermanned units have six months to solve their staffing shortage before they’re placed on probation, then 12 months before the Air Force begins the deactivation process.

With so many programs in trouble, many schools are operating on borrowed time, the Air Force having held off on shutting down programs while waiting for a change in law to go into effect, a change leaders in Washington hope will be transformational to JROTC.

Expanded Eligibility

Traditionally, JROTC instructors have had to be retired military members who had completed 20 years or more of Active service. But Section 512 of the 2023 National Defense Authorization Act, signed into law by President Joe Biden on Dec. 23, paved the way for National Guardsmen, Reservists, and veterans with at least eight years of service to also be eligible for these jobs.

The change drastically expands the pool of eligible candidates for instructor jobs. “With this new language and opportunity, we really feel it’s going to get after … improving our instructor manning, which is at all-time lows for the Air Force,” McGonigal said. “It opens up the pool of eligible candidates to a point where we’re really optimistic that we can not only improve but maybe get totally 100 percent manning at some point in the near future.”

Positive feedback is fueling McGonigal’s optimism.

“My chief of instructor management, he’s fielding a lot of phone calls,” McGonigal said. “He’s been getting quite a few calls from Guard and Reserve who are asking about the program. We field calls in my office as well quite frequently from folks that are asking, ‘Hey, when is this going to be implemented, what’s it look like? When is it going to be show time for the new system?’”

In one case, an Air National Guard tech sergeant drove from Georgia to AFJROTC headquarters at Maxwell Air Force Base, Ala., just to ask about the new eligibility standards. Already a high school teacher in his full-time job, and with both JROTC instructor slots open in his school, he was eager to find out more.

“We’re getting enough interest in it that we think that there’s going to be a lot of opportunities … here like this tech sergeant. We think that there are already a lot of schools that have recently separated service members and currently serving Guard and Reservists who are already teaching at the school, so it’d be a relatively easy transition for them to transition over to the units if there’s one in place that already had a vacancy,” McGonigal explained.

A 2016 survey by the Department of Education identified 25,000 veterans who are high school teachers, and the Department of Defense has sought to encourage more veterans to pursue a career in education through the Troops to Teachers program.

McGonigal noted that units that had been on probation due to understaffing were granted a reprieve as the Department of Defense works out details on the new system. But one of the biggest issues the Pentagon must figure out is also a familiar hurdle for many potential JROTC instructors: pay.

In the current system, JROTC instructors are paid what they would earn if still on Active duty, including housing and subsistence allowances. The instructor’s retired pay covers much of that, DOD pays part, and the school pays the balance.

But veterans and Reservists require more up-front funding from DOD. The NDAA offered only some guidance about how this should be done, directing DOD to pay for half of every instructor’s salary, but that left the details to be worked out by the Pentagon.

McGonigal said he hoped the new pay scales will be ready this summer.

“We’re working rapidly with the Department of Defense and other services to finalize updates on the new instructor pay scale, making sure it’s fair in comparison to our current retired instructor pay construct,” McGonigal said. “As expected, this initiative will also go through a finance and legal process to make sure what we’re doing is within the law—and practical. Once complete we’ll be able to reimburse schools so they can hire and pay instructors. We’re hopeful to get this done in time to onboard people before the next school year.”

The Office of the Secretary of Defense declined to offer an early look at how the new pay scales might be structured.

For the Air Force, other changes may also be in the works. When the Budget Control Act went into effect in 2012, the Air Force decided to limit JROTC contracts to 10 months instead of a full year. If schools wanted instructors to work year-round, they had to bear the full cost during the summer.

“Some school systems actually, they’re ponying up the other two months, the few months they’re not getting reimbursed for,” Davis said. “A lot of schools won’t do that. They just haven’t put it in their budget.”

Davis said he wasn’t sure if the 10-month contracts were a deterrent or not, but they certainly weren’t an incentive to take those jobs.

But McGonigal noted instructor manning started to decline after that switch.

“We feel that that had an impact, almost immediate, and it’s been kind of declining since that point,” he said. “Our senior leaders are looking at this 12-month contract authorization right now, but as far as I know, that’s still being worked.”

Pay is certainly a factor in retention, said retired Chief Master Sergeant of the Air Force Gerald R. Murray.

“It is a fairly high turnover rate,” Murray said. “In my view and discussion, [that suggests] it does have to do with pay,” Murray continued. “Most people getting out of service—especially senior NCOs and lieutenant colonels … they’ve accomplished and risen to senior ranks in the military. … They’re in their 40s and 50s, and that’s the highest earning time frames of most people’s lives. And they’re looking out for their own families and everything, and many of them have still got children.”

Traditional JROTC pay only “keeps them where they were,” Murray said. “As one retired colonel told me, he says, ‘I really liked it.’ But then he almost doubled his salary with industry within a year after he went into the program.”

Values

If JROTC has one advantage in the fight for instructors, it’s the program’s societal impact, leaders say. JROTC is not a recruiting program so much as a youth citizenship and discipline program.

“I find most instructors that I deal with, they come to have a great deal of satisfaction that they are working to develop the future, that they really are committed to teaching and to working with youth and know that what they’re doing is great value,” Murray said. “They look at the value of the profession, if you will, instead of just a job.”

Davis views the extra work that goes into his job as a responsibility. “I want the kids to have every advantage available to them, that they’re able to compete and participate. And I guess I’m just the one that facilitates all that. And I guess that’s really my main motivation. I just want the kids to succeed, I want them to have the opportunity to do what they need to do.”

McGonigal says the program is worth fighting for.

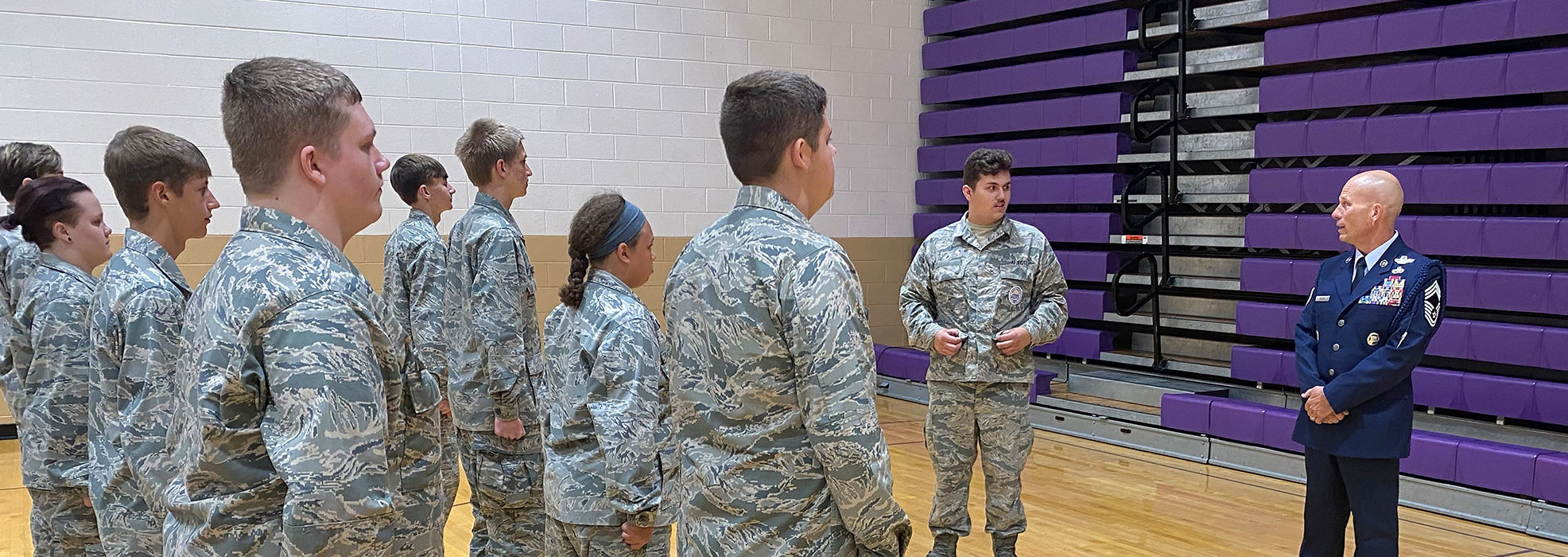

“When I go see a Junior ROTC detachment, talk to cadets and see them perform and they give me a briefing and I interact with them, my pessimism gets reversed to optimism, because I think we’re in good hands,” McGonigal said. “These cadets are our future. They have shown a propensity to serve, they want to belong to something bigger than themselves, and what they learn from the Junior ROTC program, they learn about selflessness and discipline and attention to detail and community service and a wide variety of intangible and tangible benefits that they’re not going to get in any other program.”

While many cadets are drawn to the program because of interest in the military, they won’t all go on to futures in the military.

“We ask the kids every year, ‘Why did they get into JROTC?’” Davis said. “And we have various answers, like, ‘My mom made me,’ or ‘My dad made me,’ or ‘I just wanted to see what it was like,’ or ‘I want to go in the military.’ It’s about half-and- half—some kids who just wanted to see what it was like, the other half, they’re thinking about going to the military and they think that that’s the way to do it.”

Changes

Like any government or schools program, JROTC has had its share of controversy. The New York Times reported last year on sexual assaults in JROTC programs, and also on instances of schools automatically enrolling some students in the program.

In a November 2022 congressional hearing, Air Force Assistant Secretary for Manpower and Reserve Affairs Alex Wagner told lawmakers that the department was reviewing its oversight measures and working to hire more female instructors.

McGonigal said women instructors make up “around 10 percent right now,” but Wagner’s goal is to drive that up to “closer to 40 percent, which is more representative of our student cadet corps.”

To raise awareness and assurance about abuse concerns, DOD now has a Childcare National Agency Check and Inquiry screening for all instructors. And McGonigal said any school district found to be forcing students into JROTC against their wishes will lose accreditation.

The bigger issue is keeping programs going.

“Most schools, they’ve got really good support,” Davis said. “Most schools want to keep their ROTC program. They are an advantage. I think they help the school.”

McGonigal said shifting to younger teachers will also keep the programs fresher and more closely related to the modern military. “A lot of our retirees have been in this [ROTC] job for nearly 30 years,” he said. “They haven’t been in the military for a while. So if you have an actively serving Guard or Reserve [member] … they have recency and relevancy in the current operational military. … They could speak to current events, current technologies, current opportunities.”

In some cases, the Air Force will seek to shift the presence of JROTC programs to better reflect the nation. “We have a mandate to fairly distribute our units across the United States,” McGonigal said. “So this is an opportunity to close units in overrepresented states.” McGonigal emphasized that experience, whether recent or less so, is key to JROTC’s goal of promoting good citizenship.

At Crest in North Carolina, Air Force JROTC has been in place since 1994. That’s almost 30 years.

“We’re coming up on the anniversary year in another year,” Davis said. “We’ll definitely hit the anniversary. I just hope that I won’t be the last ROTC instructor at Crest High School.”