Secretary of Defense Lloyd J. Austin III announced new steps in a multiyear plan to improve mental health and suicide prevention in the military on March 16—issuing a memo outlining 10 steps the Pentagon will take at the recommendation of an independent review committee.

However, Austin deferred action on some of the committee’s recommendations, saying more analysis is needed in the form of a Suicide Prevention Implementation Working Group. In particular, Austin said the working group will assess the feasibility of, and put together a plan for, long-term steps such as more closely regulating firearm purchases by service members on Department of Defense property and modernizing the suicide prevention education curriculum.

The working group will present its findings to Austin by June 2, the memo states.

“We all share a profound responsibility to ensure the wellness, health, and morale of the Total Force, and the steps outlined in this memo will help us deliver on that priority,” Austin wrote in the memo. “We must do everything possible to heal all wounds, whether visible or invisible, and we must do away—once and for all—with the tired old stigmas on getting help.”

The Suicide Prevention and Response Independent Review Committee (SPRIRC) formed last March and visited bases around the world, speaking with focus groups and individuals to create a sweeping report on the issue which was published on February 24.

The 115-page report makes 127 recommendations that are centered on four “strategic directions”: healthy and empowered individuals, families, and communities; clinical and community preventive services; treatment and support services; and surveillance, research, and evaluation. The recommendations were also grouped into high, moderate and low priority.

Of the 10 recommendations that Austin announced would be implemented, two were marked high priority, five were moderate priority and three were low priority. Pentagon Press Secretary Brig. Gen. Pat Ryder told reporters the 10 recommendations were chosen because they could be implemented quickly.

“There are areas where the department already has the authorities necessary to take immediate action,“ he said. “So that was the primary driver, was of those recommendations, what are the things that we can move on right now that will make a difference for our service members?”

Tough steps ahead

The two high-priority recommendations are expediting the hiring process for behavioral health professionals and having commanders at all levels “promote mission readiness through healthy sleep throughout the Department.” Other recommendations include expanding opportunities to treat common mental health conditions in primary care and ensuring the availability of evidence-based care for people seeking treatment or support for unhealthy drinking.

The second phase of Austin’s plan involves establishing a Suicide Prevention Implementation Working Group. The group will assess the advisability and feasibility of the remaining 117 recommendations, identify specific policy and program changes needed to implement them; provide cost and manpower estimates required to do so; provide an estimated timeline for implementing each recommendation; identify barriers to implementation; and find out which recommendations can be synchronized with actions pursued by the separate Independent Review Commission on Sexual Assault in the Military.

The working group faces a difficult task, especially because some of the recommendations may prove controversial or difficult to implement.

Likely to cause the more uproar of the 23 high-priority recommendations, are seven that have to do with more closely regulating the purchase and storage of firearms by service members. One high-priority recommendation is to raise the minimum age for buying firearms and ammunition to 25 years on Department of Defense property, while another is to implement a seven-day waiting period for any firearm purchased on Department of Defense property, and a third is to allow the Department of Defense to collect and record information about department members’ privately owned firearms.

In its report, the SPRIRC wrote that 66 percent of active-duty suicides involved a firearm, as did 72 percent and 78 percent of Reserve and National Guard suicides, respectively.

“Several lines of evidence suggest that limiting or reducing firearm availability could dramatically reduce the military’s suicide rate,” the committee wrote. “For example, a simple policy change requiring Israeli military personnel to store their military-issued weapons in armories over the weekend led to a 40 percent reduction in the Israeli military’s suicide rate.”

Implementing some of these measures would require Congress to repeal sections of military law, a tall order given some lawmakers’ fierce opposition to gun control laws. Even efforts like collecting information about service members who own firearms have been blocked through laws like the 2011 National Defense Authorization Act—though one military lawyer told the SPRIRC that such information was useful to commanders.

“I used to be able to ask if [fellow service members] have weapons” the lawyer said. “Allowing commanders to know if a service member has a firearm off-post would be very useful; I have heard commanders lament that.”

A Wicked Problem

Other measures that do not involve firearms could be expensive or complicated to implement. For example, one high-priority recommendation is to fix pay systems so that service members are not paid late, a concern which caused considerable stress across the military, the committee found.

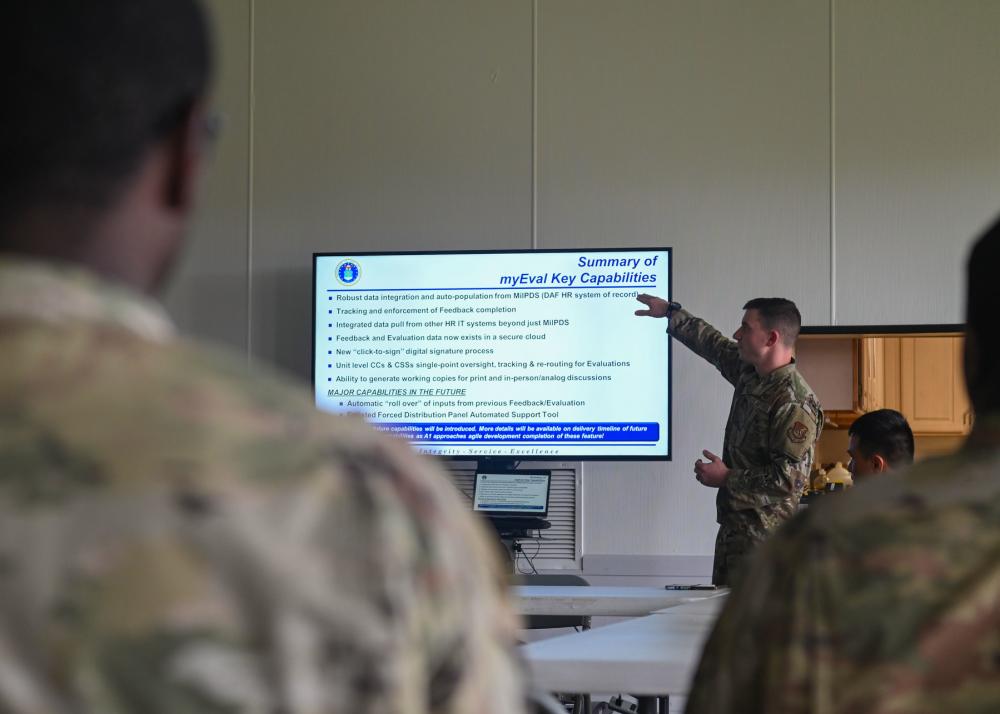

Fixing such a problem would require solving longstanding problems with the military’s personnel databases and systems—and the services are already struggling with platforms like the Air Force’s widely-despised myEval.

“The combination of poorly functioning systems with downsized workforce reduces productivity, increases work-related stress, and creates financial strain across the entire force,” the SPRIRC wrote. “Personnel must also work extended hours to compensate for these deficiencies, disrupting social support networks and creating relationship strain within military families.”

Another ambitious high-priority recommendation is to create a task force to reform the military promotion system in order “to better reward and select the right people for the right positions at the right time based on demonstrated leadership skills and abilities.”

The military puts too much emphasis on quantifiable skills “that have little to no bearing on leadership potential (e.g., number of jumps, number of patients seen) … resulting in the promotion of individuals with good technical skills but poor personnel management abilities,” the SPRIRC wrote. The committee cited the Army’s Battalion Commander Assessment Program as a potential model for reform.

Promotions and pay systems may not seem obviously connected to the suicide issue, but the SPRIRC report noted that making such connections is necessary to address the root causes of the problem and make progress.

“Wicked problems are difficult to solve because they involve complex interdependencies,” the committee wrote. “To address a wicked problems like suicide, the DOD must reduce its reliance on solutions-oriented thinking and adopt process-oriented thinking instead.”

Though the problems sound daunting, the SPRIRC found a widespread desire across the force to do something about them.

“You [service members] overwhelmingly supported the DOD’s efforts to prevent suicide as the right thing to do,” the committee wrote in its report. “While some current efforts were not seen as effective, you did not hesitate to reinforce the importance of suicide prevention practices and helped us consider different options to decrease the risk of suicide among those in uniform.”

Austin echoed the sentiment.

“We will find new ways to support all who are in pain,” he wrote. “And we will redouble our effort to do right by every member of our outstanding military community.”