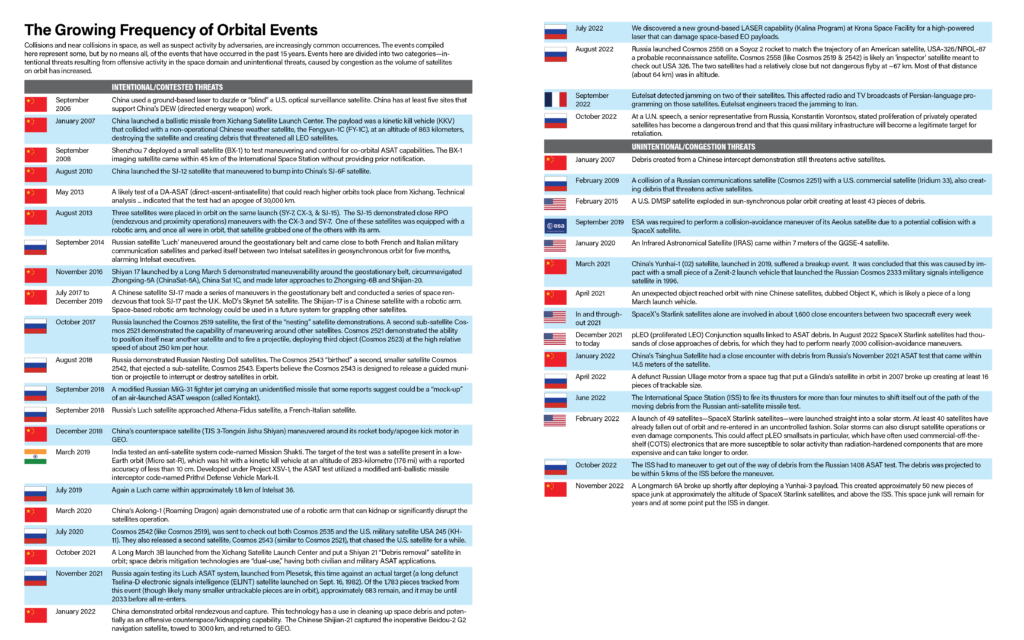

The growing frequency of intentional and unintentional incidents in space proves the case for resiliency.

“Both Russia and China have been building space systems to support their military, operationally and for strategic reasons, and they both have been working on offensive capability to counter our space systems. … Preventing a conflict over space assets is going to become increasingly difficult due to the strategic value of satellites and the proliferation of technologies that can be used to destroy satellites. The United States wants space to be a peaceful domain for scientific and commercial pursuits.”

— Secretary of the Air Force Frank Kendall, September 2022

The U.S. military depends on a vast array of capabilities supplied from space: precise navigation and timing; wideband, protected, and secure communications; missile defense missile warning and missile tracking; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance; and environmental and weather monitoring. Each of these is critical to the U.S. and allied defense, both in peace and war. Increasingly, there is also a vibrant international commercial economy built around satellites operating in a variety of orbits. All of these capabilities are now under threat from both intentional and unintentional interference. Threats range from permanent destructive attacks to the reversible effects of jamming. Meanwhile, China, Russia, and others are not only focusing on counterspace weapons, but developing their own space assets, as well.

Protecting and retaining U.S. space capabilities in this threatening environment is critically important. Both the military and civilian worlds now depend on capabilities such as the Global Positioning System, communications, and other systems must be secure and protected. Across the world we are dependent on missile warning and missile tracking to assure the safety of our society, infrastructure, and troops on the ground, U.S., and allies. If the space systems that we so depend on are interfered with and unavailable, the consequences could be dire.

China and Russia have developed capabilities that threaten U.S. space dominance, including the ability to eliminate satellites. The Space Force, in response, has moved and adopted a strategy of affordable resilience, using proliferation as its centerpiece. In addition to proliferation, however, there are many more strategies needed to support resilience. In this rapidly changing and evolving threat environment, the more options we have available, the better we can flexibly respond to new challenges.

Menu of Responses

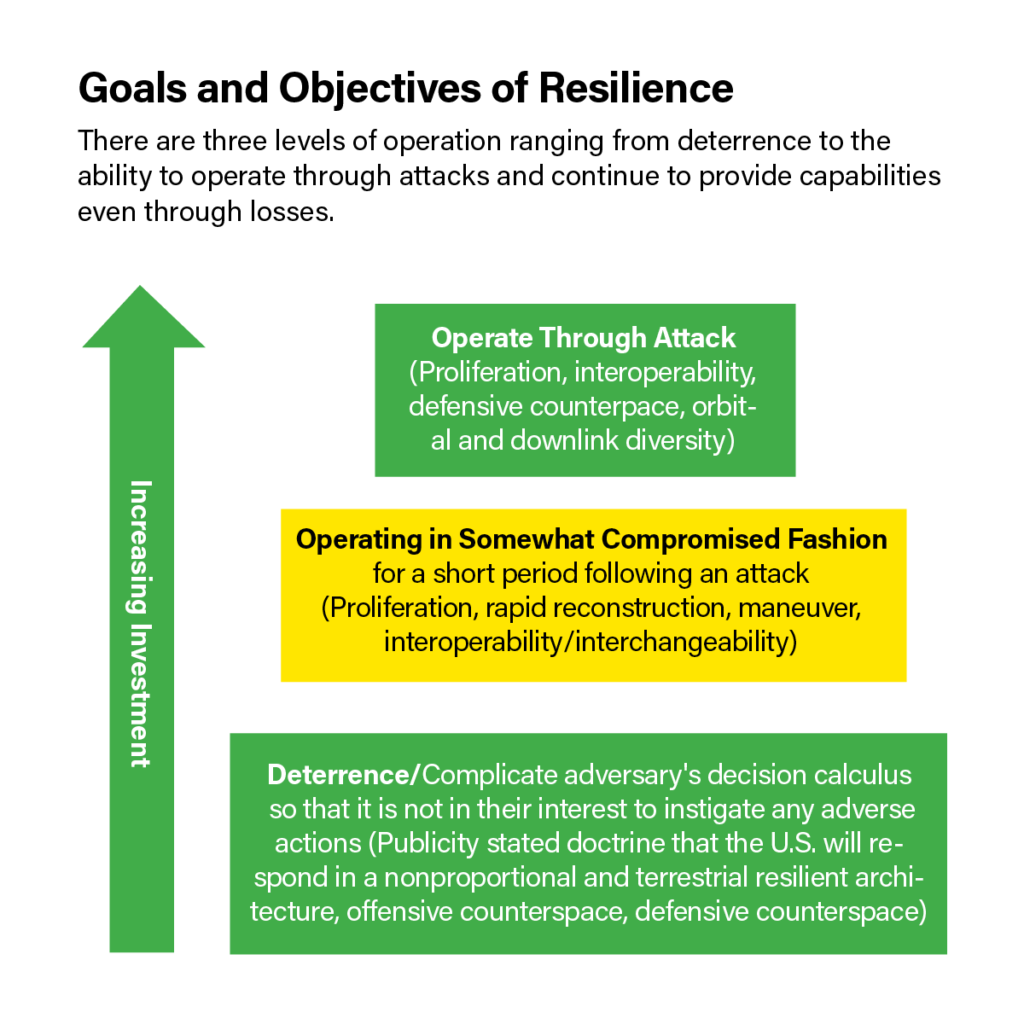

What do we do about these intentional and unintentional threats? The solution is to apply multiple strategies to assure that we can provide resilience in space operations—that is, the ability to absorb losses and continue the mission, even if that capability is degraded. The most critical of these tools are:

- Offensive counterspace

- Proliferation, with large constellations of satellites

- Reconstitution, or the ability to rapidly replace satellites by launching existing ground spares

- Defensive counterspace

- Mission disaggregation

- Orbital diversity

- Downlink diversity

As Lt. Gen. John E. Shaw, deputy commander of U.S. Space Command has said, “Our adversaries see what space capabilities mean to modern warfare, and how dependent our terrestrial forces are on space. These capabilities are fundamental to how the U.S. does warfighting, and they are now under threat, and can be held at risk. The U.S. military now treats space as an ‘area of responsibility,’ territory that needs to be maintained and defended, not merely traversed by spacecraft, and to protect and defend our space capabilities against those threats and be prepared for a fight that may begin or extend into space.”

Offensive Counterspace

The definition of deterrence is “the action of discouraging an action or event through instilling doubt or fear of the consequences.” While increasing our adversary’s complexity of attack is indeed some level of deterrent—especially where the cost trade-off is unattractive—the ultimate deterrent is to be able to react in kind in a fashion such that our adversary cannot effectively respond.

Offensive counterspace can involve jamming signals; spoofing; using lasers to dazzle or blind optical satellites; using lasers to damage the satellite; physical disruption, either by means of collision or the use of a robotic capability to grapple or “kidnap” a satellite; and kinetic attack by means of a projectile, whether launched from inside or outside Earth’s atmosphere.

Proliferation, including the availability of orbiting spares, is one way to counter offensive space. Moving to larger constellations of more affordable satellites is a cornerstone of resilience. Having more satellites on-orbit than necessary allows the constellation to absorb losses and still accomplish the mission.

Another approach is to use ground spares to rapidly reconstitute capability in the face of losses in battles of attrition. The U.S. Space Force must be able to rapidly replace satellites and retain resilience, requiring that replacement satellites be ready to launch, and that these can be launched quickly with a tactically responsive launch capability. The Space Force’s Space Systems Command (SSC) plans to demonstrate this capability sometime in the next year. Additionally, as threats to our satellites expand and change, agility—that is, the ability to reprogram hardware already in space—is far preferable to building and launching new hardware. All new systems must have the ability to be reprogrammable and to use this reprogrammability to the maximum extent possible to flex against new and changing threats.

Defensive Counterspace

Being able to negate attacks will be critical in the future. Defenses must be flexible and adaptable, lest adversaries change to attacks for which current defenses are not effective, leaving the U.S. vulnerable. But like proliferation, defense is a key element of any resilience strategy. Defenses can include active kinetic defense; cyber hardening; anti-spoofing; survivability; and the ability to maneuver out of the path of attacks.

Mission Disaggregation

The ability to accomplish the mission across more platforms through separating out, breaking up missions into smaller mission bites, and having systems designed for other missions being able to support disparate missions, increases resiliency, decreasing the effectiveness of eliminating satellites.

Orbital Diversity

As national security and commercial space evolves to include proliferated constellations, a variety of orbital options (both in altitude regimes and in orbital inclinations) are available. Each has advantages and disadvantages.

Orbital diversity complicates the calculus of adversaries because it is more difficult for an enemy to defeat a complex and multi-layered system than to attack a single homogeneous element. Orbital diversity forces adversaries into multiple attack approaches, complicating their ability to negate U.S. advantages in space. As the Space Force moves toward resilient constellations, it should continue to seek diversity in orbital regimes, diversity in orbital inclinations, and ground diversity.

The rapid evolution of the capability to launch many small SVs on a single launcher seems to be increasing the opportunities of having highly proliferated and orbitally diverse systems, each of which is relatively inexpensive, so long as the communication challenges posed by this diversity can be addressed. The Space Development Agency (SDA) is actively taking on this challenge with a “Transport Layer,” adding evolving Optical Inter-Satellite Links (OISL), which link satellite to satellite, in-plane and cross-plane, with high-rate downlinks that exponentially increase the utility of these proliferated systems.

Downlink Diversity

As the SDA implements this Transport Layer, using high-rate optical links, there is also significant future potential for high-throughput optical technology to exceed data rates possible today with radio-frequency links, not just for space-to-space connections, but also space-to-ground. In addition to the potential of higher data rates, there is also a case for diversity and redundancy in ground network systems, as well as in space sensing and networks. Optical links to the ground are dependent on weather, but optical communications terminals (OCT) can be incorporated into Ground Entry Points (GEPs). Like with orbital diversity, single-GEP solutions are more vulnerable to outages than the diversity of multi-GEP solutions.

Space Systems & Domain Awareness

Lt. Gen. Michael A. Guetlein, commander, Space Systems Command, stressed the need for improved space systems and domain awareness in September 2022. “With space essential to military operations, better understanding of what objects are in orbit and the threats they may pose is foundational for space security,” he said. “It’s incumbent on the service to better track potential threats to those assets. The days of us focusing only on maintaining the space catalog of knowns is over. Not only are we focusing on what we know is out there, we’re searching for new objects. We are identifying where those objects came from, why they are there, and what their intents are.”

Space Systems Awareness (SSA) and Space Domain Awareness (SDA) require the ability to detect and track man-made (intentional) and natural (unintentional) threats. It means determining the capabilities of the objects, the intent behind their launch, and the vulnerabilities of U.S. and allied assets to potential attacks. It also requires the ability to predict and assess the risks involved, and to maintain custody of threats and potential threats, and to implement appropriate mitigation measures in order to protect space and ground assets.

As Army Gen. James H. Dickinson, commander of U.S. Space Command, put it in an interview with reporters in August 2021: “Space Situational Awareness (SSA) is more than simply reporting on where something is in space—but also characterizing it that way. Space Domain Awareness (SDA), is a little bit more complicated, requiring observers to try to understand and assign motive, the ‘why’—the intent—behind having something in space and where it is. SDA gives us insight into activity throughout the space domain, including potential adversary activities, but perhaps more importantly, insight into the intent of those potential adversaries, too.”

SSA/SDA must provide the effective identification, tracking and custody, and characterization of threats to U.S., ally, and commercial space systems. The goal is to understand any factor, passive or active associated with the space domain that could affect U.S., ally, or commercial space operations and thereby impact the security, safety, economy, or environment of our nation. These systems can be space based or terrestrial, government or commercial, radar or optical.

Before retiring from the Air Force in 2021, then-Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. John E. Hyten emphasized how essential space resilience is to American forces in every domain. “Our No. 1 priority,” he said, “is to get the Soldiers, Airmen, Guardians, Sailors, and Marines deployed in harm’s way all around the world the space capabilities they need—every minute of the day—because everything they do is critically dependent on space. We cannot fail that mission.”

Space no longer is an arena of free and open operations. However, there is a growing threat environment, and missions must continue despite these threats, even when they can successfully eliminate satellites/nodes of our space systems. There are various approaches to achieve resilient architectures, and while proliferation is the primary cornerstone, we must also assess and implement other resilience options where they are appropriate.

Thomas “Tav” Taverney is a retired Air Force major general and former vice commander of Air Force Space Command.