The Air Force’s first new bomber in a generation is the key to ensuring an American advantage in range, payload, and survivability to fight.

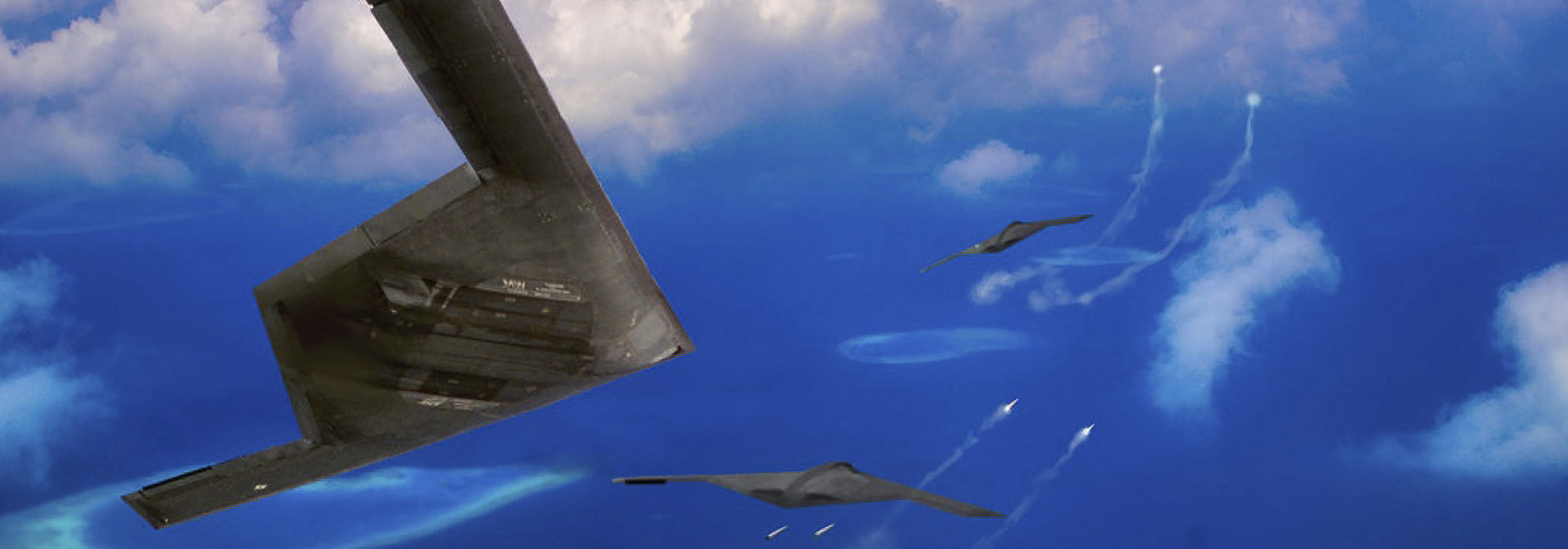

In this new era of great power competition, fielding the stealthy B-21 Raider bomber on time and in volume is a national imperative. The B-21 is an indispensable capability for delivering responsive and lethal global power in the future. When fielded, it will be the only dual-capable, long-range, survivable capability that can penetrate advanced air defenses to hold peer adversaries’ highest-valued targets at risk. Without the B-21 eliminating adversary Anti-Access / Area-Denial (A2/AD) capabilities which restrict the freedom of U.S. and Allied forces to maneuver, seizing and maintaining the initiative in a war primarily with capabilities such as standoff weapons, would be much more difficult, would take much longer, and would be much less cost-effective.

Today, the U.S. long-range bomber fleet is the oldest, smallest, and most fragile it has ever been. Except for the B-2, U.S. bombers cannot survive in highly contested air space. Fielding a robust force of B-21s is the only way the United States can maintain the range and payload advantage it enjoyed in past conflicts. Mass is still as important in future war as it was in past wars. The ability to inflict multiple, simultaneous dilemmas on an adversary is vital to creating compounding opportunities for Combatant Commanders to exploit. Long-range B-21 strikes in concert with other asymmetric capabilities, such as offensive cyber attacks and electromagnetic spectrum operations against sensors and command and control systems, degrade an adversary’s ability to sense, decide, and act miring them in the proverbial fog of war. Once an adversary is denied the information it needs to defend itself, B-21s and other 5th and 6th generation platforms can then systematically degrade their ability to sustain offensive operations, leading to its defeat.

Among the long-standing principles of war, surprise is one of the most valuable: Surprise creates shock, confusion, and indecisiveness. It degrades an enemy’s operations and produces opportunities for the attacker. Confronting adversaries in unexpected ways forces errors, exposes vulnerabilities, and ultimately slows their ability to react effectively in a timely manner.

U.S. bomber forces have long been used to achieve surprise; The raid on Tokyo led by then-Lt. Col. Jimmy Doolittle may be the best-known example of this. The April 18, 1942, Doolittle Raid caught Japan’s military by complete surprise and demonstrated that Japan’s homeland was not an operational sanctuary. Doolittle’s Raiders, flying 16 twin-engine B-25s off the deck of the U.S.S. Hornet, dealt a significant psychological blow to Japan and provided a much-needed morale boost for the American people. While the raid achieved little damage, it convinced the Japanese government to change its plans and direct valuable resources elsewhere to prevent another U.S. attack by air. Then, as now, air power can exacerbate a nation’s sense of insecurity because the speed, range, and maneuverability of aircraft make them harder for an adversary to counter than slower moving ground or naval forces.

Today, 80 years later, the stealthy long-range B-21 promises to create even more challenging dilemmas for adversaries. The B-21 Raider will be the most survivable, most lethal, and most cost-effective combat aircraft ever built. The B-21 is an invaluable investment in the Nation’s security, to be sure, providing U.S. commanders an incredible capability to deny adversaries operational sanctuaries. They create an imposing deterrent, as few adversaries would subject themselves to B-21 attacks against which they have no defense. When deterrence fails, B-21s can attack any target, anywhere on the globe within hours—and at much less risk than virtually any other instrument of U.S. power. Moreover, the larger the B-21 fleet, the greater its deterrence value.

The dual-capable B-21 is as much a key to the next offset strategy, and Integrated Deterrence, as are nuclear submarines; maybe even more so because of the inherent economic value in a capability that can create both conventional and nuclear effects. Instead of trying to respond to an opponent’s strengths, the goal of an “offset” strategy is to impose burdens (financial and/or geopolitical “costs”) to change strategic behavior by affecting their decision-making calculus. Simply stated, the goal is to force a competitor to invest resources in defense at the cost of offensive capabilities. The goal of such a cost-imposing strategy, then, is not just to ensure victory in war through technological overmatch and mass, but also to deter war in the first place by driving up the cost to defend against superior technology at the expense of the capability to wage war. The B-21 achieves this by growing a U.S. advantage—next-generation low observable technologies—faster than adversaries can react and adapt. During the Cold War, the U.S. planned to build 132 B-2s and 100 B-1s with the aim to bleed the Soviet military economy dry by forcing them to defend against these superior U.S. strategic capabilities. That same strategy applies today.

As with any deterrence strategy, the end goal is to make war unattractive, unaffordable, and unwinnable in the adversary’s eyes. Historically, bombers provided a flexible, visible tool for U.S. national security leadership to wield during a crisis. They can be “flexed” —flown next to a country’s borders, for example—to signal U.S. resolve and deployed in a crisis far faster than ground or naval forces. And, unlike forward-based ground and naval forces, bombers can operate from distant bases, a disincentive to adversaries launching a preemptive strike.

Complicating the adversary’s dilemma even more is the B-21’s ability to deliver either conventional or nuclear weapons. The cost to counter a robust force of penetrating B-21s far exceeds the cost to develop, build, and sustain this revolutionary weapon system. The return on investment is invaluable.

Challenges to Existing Methods of Power Projection

The world has changed since Secretary of Defense Bob Gates approved the requirements for the then named “LRS-Bomber” (B-21) program in 2011, but the need for the Raider has only grown greater. China is aggressively attempting to assert itself as the Indo-Pacific region’s economic and military leader and is backing up its ambitions by rapidly expanding the capacity and capability of its armed forces. To this end, it is fielding three aircraft carriers, low-observable aircraft, long-range air-to-air missiles, and hypersonic missiles such as the DF-21 and Fractional Orbital Bombardment System.

Like the United States, China enjoys a geographic “moat”—the Pacific Ocean. On top of this inherent advantage, it has mounted an aggressive campaign to deny any potential adversary the freedom to operate and sustain military forces inside the Western Pacific’s Second Island Chain. As Dave Ochmanek points out in his RAND paper Determining the Military Capabilities Most Needed to Counter China and Russia, both “China’s and Russia’s anti-access and area-denial capabilities are expressly designed to keep U.S. and allied forces at arm’s length and to suppress U.S. and allied operations for a period of time that is sufficient to allow the imposition of a fait accompli.” An increasingly contested environment poses significant challenges to U.S. power-projection in the Indo-Pacific.

To prevail in conflict, U.S. Combatant Commanders require the capability and capacity to create large-scale effects in the battlespace in the shortest time possible. China’s A2/AD strategy blunts U.S. efforts by reducing the efficacy of its land- and carrier-based strike systems. Threats to forward bases along the Western Pacific’s First Island Chain, combined with an ever-increasing mobile ballistic missile threat to Navy carriers, means U.S. forces must overcome enormous distances to attack Chinese targets.

A war against China in the Indo-Pacific would not be like the permissive contests seen in Iraq and Afghanistan, but instead would be characterized by:

- Intense ballistic and cruise missile attacks, as well as on airbases and ports

- Enemy bomber attacks, on U.S. and allied airbases and ports

- Anti-ship ballistic and cruise missile attacks on Navy surface ships and carriers by an increasingly powerful PLAN surface fleet, submarine fleet, and naval aviation

- Advanced enemy fighters with long-range air-to-air missiles (e.g., J-20 with PL-15) capable of threatening U.S. AWACS, tankers, and less survivable non-stealthy missile launching aircraft at range

- Advanced, long-range, enemy air defense systems designed to deny access to non-stealthy aircraft

- Adversary targets that are hardened, underground, mobile, or are beyond the reach of standoff weapons

- U.S. and Allied forces would be subject to relentless cyberattacks and information warfare measures throughout all stages of the conflict.

It is easy to see why the B-21 is a central requirement for any future conflict in the Indo-Pacific—there are no other U.S. capabilities that can reach, penetrate, and persist throughout the theater within hours, not days, weeks, or months. No other U.S. capability can operate from more bases located in northern Australia or other distant areas where the density of Chinese missile attacks would be spread thin. No other U.S. or allied capability can more effectively overcome the “tyranny of distance” of the Indo-Pacific and the great geographic depth of China to deny the People’s Liberation Army operational sanctuaries.

Numbers are important: creating and exploiting the element of surprise requires operations at scale. U.S. forces must have the capacity to create dilemmas, exploit an enemy’s indecision, and rapidly destroy its highest value, most critical targets from day one of a conflict. Germany’s Luftwaffe learned this the hard way during World War II, when it attempted to gain a qualitative edge over Allied air forces by deploying jet fighter technologies. The Luftwaffe’s Me-262 was over 100 mph faster than Allied fighters, but the Germans produced only 1,430 Me-262s compared to 30,000 American P-51s and P-47s. Even a 4-to-1 kill ratio in favor of the Me-262 was insufficient for Germany to regain air superiority over its homeland. Vastly superior numbers helped the allies overcome a technologically superior, but much smaller German force. The takeaway: Quantity is just as important as quality. Mass remains an important element in dominating and dictating the tempo of a war.

A minimum of 100 B-21s is the current capacity requirement. Air Force officials have acknowledged that the number needed may be upwards of 145. Given the National Defense Strategy’s focus on China as the pacing threat, it is important for the U.S. to make decisions now to procure the B-21 force it needs for the 2030’s and beyond.

Attributes that Count

Stealthy bombers are defined by three key attributes—range, payload, and survivability. These attributes underwrite their ability to perform multiple missions and strike multiple targets in a single sortie. The combination of long-range, endurance, and large payloads combined with survivability make modern penetrating bombers ideal platforms for multiple missions in A2/AD environments such as maritime strikes, suppression/destruction of enemy air defenses (SEAD/DEAD), strategic attacks, and close air support (CAS). This is a radical shift from roles bombers performed during the Vietnam War, when B-52s conducted carpet bombing operations over the jungles of Vietnam. B-1s and B-52s continued to use this tactic of employing large payloads of unguided munitions to ensure targets were destroyed in Operation Desert Storm in 1991 as well as in Operation Allied Force against Serbia in 1999. Mass, then, was required to overcome inaccuracy, but the introduction of the GBU-31 Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), first employed by B-2s during Allied Force, revolutionized bomber efficiency forever.

Just as stealthy F-117 fighters and their laser-guided bombs were a game-changer in Operation Desert Storm, B-2s dropping up to 16 JDAMs per sortie revolutionized air warfare in 1999. GPS-aided munitions were accurate to less than 10 feet versus thousands of feet in World War II. Bomber strikes shifted from “one bomber, one target” to “one bomber, many targets.” Today’s B-2 can strike 80 targets on a single sortie. After Allied Force, B-1s, B-2s, and B-52s using GPS-aided munitions proved central to the post-9/11 campaigns in Afghanistan and Iraq. There, employing JDAM enabled bombers to conduct close air support, which was once considered only a fighter mission. Lt. Gen. Bob Elder, former 8th Air Force Commander, describes the metamorphosis of the strategic bomber succinctly: “Their enduring success is the result of their inherent flexibility and adaptability.”

Today, U.S. bombers outfitted with beyond-line-of-sight datalinks and carrying a large variety of different and in-flight reprogrammable weapons have literally become flying vending machines in the sky. They can satisfy most everyone’s needs on a single sortie. Today, a bomber can take off from the U.S. mainland with zero targeting data, receive updates enroute, fly for tens of hours, and strike from inside or outside of an adversary’s air defense system. B-1s with intercontinental ranges and aerial refueling can employ 24 2,000-lb JDAMs per sortie, weapons that are reprogrammable in-flight. Fighters are capable of long-range missions, but it would take multiple fighters to achieve the same massed effects as a single bomber—and many more aerial refuelings to achieve comparable effects.

B-21s will provide a whole new meaning to “affordable mass” because they will be able to get close enough to targets to employ lower-cost munitions. Maj. Gen. Jason Armagost, Director of Air Force Global Strike Command Plans, Programs, and Requirements, emphasized the importance of affordable mass when he stated that future munitions “need to be relevant—and part of that relevance is cost—and we need a sufficient volume of fire.”

The Value of Range

Despite their large sizes, bombers are extremely agile and can deploy over intercontinental ranges more quickly, easily, and with less complexity than shorter-range aircraft. To cite just one example, a bomber launching directly from its airbase in North Dakota could reach a target area in the Indo-Pacific with just a single aerial refueling.

Distance is the greatest impediment to U.S. and Allied forces operating in the Indo-Pacific theater. Very few military assets can create a wide span of effects over long ranges. Aircraft carriers may need to standoff 1,000 to 1,500 nm from China’s coastline to reduce the threat of anti-ship missile attacks. This greatly reduces the potential for carrier-based fighters, whose combat radius to launch strikes or accomplish other missions is too short to bridge that distance. Furthermore, they can’t achieve the speeds quickly penetrate the battlespace, then retreat. Many long-range stand-off weapons still lack the range to hit deep targets; they are also expensive and less effective against mobile, hardened, or deeply buried targets. Sea-launched and ground-launched long-range hypersonic weapons are even more expensive and require target intelligence updates in-flight to be effective against mobile and relocatable targets that can quickly change their positions. The B-21 not only solves these range problems but expands options for U.S. commanders to penetrate and persist in contested areas to find and attack time sensitive mobile targets.

The Value of a Large, Flexible Payload

Bombers are very cost-effective platforms to deliver precise and decisive effects. B-21s with the ability to penetrate and persist in an adversary’s airspace, combined with a deep magazine, can not only attack and destroy multiple targets per sortie, but it can also launch large salvos of weapons or decoys to overwhelm and destroy adversary air defense systems, creating access for other assets to contribute to the fight.

A bomber’s cavernous internal weapons bays are a dream for weapons innovators. Additionally, it is far easier to develop long-range weapons for a bomber than a fighter, as the size of the weapons bay limits the size of the munitions they carry and the target effects they can create. Small weapons bays also limit the effects fighters can achieve in a contested environment, since carrying additional weapons externally reduces their survivability. The less survivable a platform is, the more dependent it is on standoff weapons to counter enemy air defenses. This means they must use larger, longer-range weapons to reach their targets, raising the cost per strike. The ability to defeat critical hardened and deeply buried targets, such as command and control bunkers or Iranian nuclear facilities, is possible only with specialized munitions delivered by a penetrating stealthy bomber.

A modern product of digital knowhow, the B-21 will have the ability to rapidly integrate new software and even hardware, ensuring its lethality and survivability not only in the short term, but over its entire service life. The B-21 will be able to rapidly evolve and grow to meet new requirements.

The Value of Survivability

Denying sanctuaries to an adversary is a strategic imperative in warfare; no adversary should be afforded the luxury of employing its most damaging capabilities with impunity.

The proliferation of very capable modern air defense systems means that future combat aircraft must be extremely survivable to accomplish its mission. Many high-value targets are now protected by advanced air defense systems and by locating them deep inland rather than on an accessible coastline. Countries like China and Russia are taking advantage of their strategic depth to create geographic sanctuaries for such targets, placing them increasingly out of range of short-range strike aircraft and even stand-off weapons launched from outside an integrated air defense system’s reach.

This is why low observability is now and will remain the price of admission for air warfare. Stealth is a requirement for any combat aircraft that must attack targets in A2/AD environments including inside and adversary’s national borders. In the 1970s, advances in materials and computing technology made stealth a reality. Some 40 some years later, advances in stealth technology continue to provide U.S. warfighters with a significant advantage. Stealth does not make an aircraft completely invisible to sensors. Stealth makes an aircraft invisible enough to make detection infrequent, and the data adversary sensors receives is ambiguous enough that an adversary cannot definitively connect the dots fast enough successfully engage. The effectiveness of stealth is further enhanced when coupled with other capabilities such as electronic warfare and cyberattacks that deceive, degrade, or even destroy an adversary’s air defenses. Stealth can reduce the number of supporting aircraft and other capabilities required to attack a target while reducing attrition.

Standoff Weapons versus B-21 Penetrating Strikes

Standoff weapons are vital to defeating an adversary such as China, but they are less effective against mobile targets. Realistically, without a datalink or autonomous capability, the time-of-flight of current stand-off weapons is too long to strike mobile or relocatable targets over long ranges. Furthermore, standoff weapons cannot carry the very large warheads, such as the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator or GBU-72 Advanced 5K Penetrator, needed to attack hardened and deeply buried targets. They also lack the range to strike targets deep in China’s interior when launched by non-survivable legacy aircraft beyond Chinese airspace.

Only a penetrating bomber can effectively persist in contested areas to find, identify, and attack highly mobile missiles that keep U.S. aircraft carriers and other forces out of the fight, or anti-satellite weapons located deep in China’s interior that threaten U.S. space assets.

Precision is a significant differentiator between penetrating aircraft such as the B-21 and other long-range weapons that rely on other sources to provide targeting data and target updates. Penetrating bombers such as the B-21 can close kill chains organically—that is, with little to no off-board help— in contested and highly contested environments. Off-board data from other aircraft or space-based sensors can be used to cue a target search, but because the B-21 can penetrate, it can self-target with onboard sensors and eliminate target location errors created by a target’s movement. This is an essential discriminator. Being able to verify offboard intelligence and positively identifying targets using real-time data is another penetrating aircraft differentiator.

Finally, penetrating bombers are a very cost-effective means of delivering large payloads of weapons, either direct attack or standoff or a combination of both, on targets in contested areas over a protracted campaign. Eliminating high-value targets as quickly as possible increases the resiliency and survivability of all joint force operations. For example, bomber strikes against DF-21 and DF-26 anti-ship ballistic missiles will reduce threats to Navy assets and enable them to operate inside the Second Island Chain.

Foundation of Nuclear Deterrence

Today’s nuclear deterrence environment is more uncertain than ever. Russia’s aggression against Ukraine has been marked by threats to use nuclear weapons. Iran seems more determined than ever to develop and deploy a nuclear weapon, and it was recently discovered that China is building multiple ICBM silo fields as it deploys its own nuclear triad. Most worrisome, though, is that the United States only has a nuclear treaty in place with Russia, and it doesn’t even apply to Russia’s large inventory of theater nuclear weapons. In the absence of treaties, Iran and China’s nuclear growth goes uncontained. With these facts in mind, it is no surprise that DOD’s most recent Nuclear Posture Review determined its nuclear triad—composed of nuclear-capable bombers, ICBMs, and SLBM submarines—is still necessary and will remain a vital instrument of U.S. soft and hard power for the unforeseeable future. As former Chief of Staff of the Air Force General Mark Welsh, once said, “Nuclear deterrence is the wallpaper that everything else hangs on.”

Due to their inherent responsiveness, agility/flexibility, and visibility, bombers are a cornerstone of U.S. nuclear deterrence. The ICBM is a static weapon system residing underground that has two modes of operation: standby or launch; there is no in-between. SSBNs are never meant to be seen until they are required to launch nuclear weapons. ICBMs and SSBNs are not as visible and have a very limited ability to dynamically deter or demonstrate escalation. Their deterrence value lies in their ability to maintain a constant alert status with weapons ready to launch at a moment’s notice. Bombers, on the other hand, can be used dynamically and visibly in an escalating crisis because they can be used interchangeably for conventional and nuclear deterrence missions.

Dual-capable bombers are inherently more cost-effective than the other two legs of the triad. Bomber aircrew and maintenance personnel are highly trained and proficient in both conventional and nuclear mission requirements. Upon Presidential direction, a bomber wing can rapidly transform into a nuclear force that is loaded with nuclear software and weapons and placed on nuclear alert in a matter of hours. By direction of National Command Authority, a full bomber wing can be on alert in a few days for the whole world to see.

Bombers visibly signal U.S. resolve unlike submarines and ICBMs–and they can be invisible when you don’t want them to be. Moreover, bombers are the best nuclear instrument to provide extended deterrence to U.S. allies and partners, which helps reduce the proliferation of nuclear weapons. Bombers are also more stabilizing in crises compared to SLBM-carrying submarines and ICBMs. Unlike ballistic missiles, they can be recalled after launch, and the hours it requires them to get to their launch points provides time and leverage for decision-makers to de-escalate a situation with less risk of catastrophic errors that have horrific consequences.

Conclusion

Operation Desert Storm in 1991 put the stealth revolution on full display for the world to see. The perceived sanctuary in and around Baghdad disappeared instantly as the first-ever stealth attack aircraft, the F-117, penetrated one of the most concentrated air defenses in the world, laying waste to much of what Saddam Hussein and his cronies held dear. Flying only 2 percent of the strike missions, F-117s eliminated 40 percent of all strategic targets—with no losses. From that moment on, stealth became the dominant asymmetric advantage of the United States.

Only nine years later, conflict in the Balkans during Operation Allied Force showcased yet another U.S. stealth marvel, the B-2. The B-2 engaged targets with GPS-aided JDAMs. Flying less than 1 percent of the sorties, B-2s dropped 11 percent of the munitions, and it did so while originating all its sorties from Whiteman Air Force Base in Missouri. These 30-plus hour flights highlighted the value of stealth, range, and precision.

China, Russia, and others took notice. Endless videos of F-117 and B-2 precision attacks led both to seek ways to take these advantages away from the United States, spawning their A2/AD complexes.

Fortunately for the United States, the Air Force and its defense industry partners continued to make advances in stealth materials, coatings, and sustainment. They also developed more advanced computing power and precision weapons, which all contributed to maintaining the Air Force’s position as the undeniable world leader in stealth capabilities.

The F-22 and F-35 are prime examples of the continuing technological revolution that has produced dominant warfighting capabilities for U.S. warfighters. The B-21 is the next step in this evolution, and it is even better than its predecessors. With adversary A2/AD capabilities growing by the day, the need for the B-21 has never been greater, especially in the Indo-Pacific, where penetrating long-range strike systems are the best means America has to deter or defeat Chinese aggression as required by the 2022 National Defense Strategy.

Fielding the B-21 on time and at scale is a national imperative. The Air Force’s long-range bombers exist to provide weapons and sensor density at range that enable commanders to achieve a broad array of effects against the most difficult target sets. These effects are critical to the success of all joint force operations, not just the Air Force. At a global level, the United States is the only nation on the planet now capable of achieving war-winning effects over great distances in a matter of hours. The B-21 is the capability that can provide our Nation’s leaders with a flexible, cost-effective, dual-capable instrument to deter war and—should deterrence fail—to prevail against America’s enemies.

Col. Chris Brunner, USAF (Ret.), is a Senior Resident Fellow for Air Power at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies.