Air Force Looks to Adapt With ACE

By James Kitfield

The Air Force is confronting one of the most consequential inflection points in its 75-year history, Chief of Staff Gen. C.Q. Brown Jr. told his assembled top commanders at AFA’s 2022 Air, Space & Cyber Conference. The Agile Combat Employment construct—of dispersing and frequently re-deploying forces to a myriad of bases to complicate an enemy’s targeting problem—is a centerpiece of how USAF is responding, he and other service leaders said.

Repeating his off-stated imperative to “accelerate change or lose,” Brown described the existential stakes at play in the nation’s confrontations with aggressive, authoritarian regimes in Beijing and Moscow.

“If we don’t get this right together—if we fail to adapt—we risk our national security, our ideals, and the current rules-based international order,” Brown warned.

“But if we do get this right, together; if we do adapt, we’ll preserve the freedoms we hold most dear,” support alliances, democracy, common values “and strengthen societies all around the world.”

Brown spoke against the backdrop of Russia’s ongoing war against Ukraine, with Moscow threatening nuclear attack against anyone that dares intervene, and China’s moves, a few weeks earlier, of launching ballistic missiles and military maneuvers around Taiwan, after unilaterally declaring that the roughly 100-mile Taiwan Strait was no longer “international waters.” In recent years, China has built and militarized a string of small islands to back its discredited claims over virtually the entire South China Sea.

During his first two years as Chief, “I’ve watched with pride and seen the vision of ‘accelerate change or lose’ take hold in every corner of our Air Force,” said Brown, noting that many of those changes are driven by the service’s new warfighting doctrine of “agile combat employment,” or ACE. The traditional way USAF has deployed to established bases over the past several decades “will not work against the advancing threat,” he said.

Airmen are driving the cultural transformation that ACE represents, he said. But “we must continue to develop and refine capabilities that are important to ACE: command and control, logistics under attack, resilient basing, air and missile defense—just to name a few,” he stated. Embracing ACE will also demand that “we … all be multi-capable Airmen. That’s … a mindset and technical competency, that when things hit the fan, our Airmen are ready.”

Indo-Pacific Challenge

Air Force leaders said ACE has come to dominate internal counsels and the service’s strategic plans.

“When we talk about ‘global competition,’ we’re talking about China, China, China,” said Gina Ortiz Jones, undersecretary of the Air Force. “If you don’t wake up thinking about the pacing challenge, you’re doing it wrong.”

China has long strategized around a potential attack on Taiwan, saying in a recent white paper that Beijing will resolve “the Taiwan question” and reunify China “by force if necessary.”

“We’ve also heard [Chinese President Xi Jinping] tell his military commanders to be ready to take Taiwan by force by 2027,” said Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach, PACAF commander and the air component commander to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. While the U.S. military was distracted by the “global war on terror” and counterterrorism operations in Iraq and Afghanistan for two decades, China pursued an “anti-access/area denial” (A2/AD) military strategy, chiefly by holding a handful of major U.S. air and naval bases in the Indo-Pacific at risk with its massive arsenal of precision-guided, theater ballistic missiles, according to Wilsbach.

“Traditionally, we had only a handful of very large bases in a theater, [so] our adversaries developed the capability to lob missiles into those bases and shut them down, depriving us of our air power,” said Wilsbach, adding, “we essentially had all of our eggs in one basket.”

The countermove is ACE. Shifting Air Force combat operations from major air bases to dispersed, bare-bones airfields, however, requires rethinking every level of operations, from command and control and logistics to air base defense and repair.

The ACE concept requires “expanding the number of [airbase] hubs and spokes we use, which creates extremely complex command-and-control challenges, especially in the midst of [a] dynamic…contested environment” featuring jamming and chemical/biological/radiological threats, said Wilsbach.

Reimagining C2 & Logistics

Brown recently reissued Air Force Doctrine Publication 1 to emphasize mission command and the clear articulation of “commander’s intent” to the lowest levels of command. “Leaders need to give our Airmen intent, empower them, and get the hell out of the way,” he intoned.

Air Combat Command’s Command Chief Master Sergeant John G. Storms said the Air Force must be mindful that ACE “raises the possibility that units will be operating in an environment of degraded command and control, with incomplete or inaccurate information, and oftentimes without the specialists or subject-matter experts we are accustomed to having at our big air bases.”

Junior leaders will be asked to “make the best decisions possible” under less-than-ideal conditions with the information at hand, “executing according to their commander’s intent.” On the upside, “if you’re a young leader, it’s a perfect opportunity to express your leadership abilities,” he said.

Because adversaries will surely target logistics and resupply nodes, PACAF has also been funded to sharply increase levels of prepositioned equipment, fuel, ammo, and supplies in the theater. To facilitate a much wider dispersal of air operations, PACAF is negotiating new basing and overflight rights in the region and expanding airfields and related facilities.

“In the next three to five years we’ll see the extension of runways in small islands in the Pacific, including around the Guam cluster,” said Wilsbach. Rapid airfield damage assessment and repair is also being emphasized, “so that if an airfield takes a hit, we can fill those holes and get things running again very quickly.”

The ACE concept was declared initially operational in 2021, and PACAF is now working to reach full operational capability. Its focus on dispersal and “multi-capable Airmen” is becoming second nature in the theater.

Last year, “ACE was new and sort of episodic,” Wilsbach said, but PACAF is conducting “some kind of ACE event almost every day, now.” He envisions pilots landing on remote islands in the Pacific, swiftly refueling, and getting aloft again even before being assigned their next mission.

Recently, he said, “we had an F-35 pilot land at Elmendorf in Alaska and get out of the cockpit and refuel his own jet. … I never had to do that!”

Air Mobility Adaptation

Gen. Mike Minihan, head of Air Mobility Command, unveiled his “Mobility Manifesto” at the conference, setting the ambitious goal of being ready to operate and fight inside the “first island chain” outside Chinese waters by August 2023. AMC will have a critical role in the region, given the “tyranny of distance,” he commented.

“AMC is the joint force maneuver. There is too much water and too much distance [in the Pacific] for anyone else to do it relevantly, at pace, at speed, at scale,” Minihan asserted. While “everybody’s role is critical, if we don’t have our act together, nobody wins.”

AMC leaders have set a think-outside-the-box team of functional experts called “The Fight Club.” Composed of officers and NCOs, it’s imagining what a winning, agile “scheme of maneuver” looks like against an adversary such as China.

“There are still major gaps in the concept, beginning with command and control, because this is a really huge area of operations,” said Brian P. Kruzelnick, command CMSgt. for AMC. “Contested logistics and maneuver are also very hard problems to solve,” he said, likening it to “running an obstacle course while someone is shooting at you.”

AMC runs an air expeditionary center that cross-trains Airmen on the multiple skill sets needed to arrive at an austere air base, establish security and command-and-control, and get operations underway. The center marks an advanced course in training multi-capable Airmen.

“I know [that term] freaks some people out, but if you’ve deployed in the last 30 years and you were asked to do something outside of your sole specialty, you are already a multi-capable Airman,” said Kruzelnick. “We just gave it a new name and put some structure behind it.”

Other recent ACE experiments include:

- AMC is looking at slashing crew size on aircraft like the KC-46 tanker from three to two, by eliminating the co-pilot. The command is also looking for a KC-46 crew break to current records by flying 30-hour plus sorties.

- Air Force Special Operations Command is developing an amphibious modification system to allow its MC-130J aircraft to take off and land on water.

- The Hawaii Air National Guard’s 199th Fighter Squadron has experimented with deploying its F-22 Raptors supported by just one pallet of parts and equipment, which can be moved by a C-130 transport or even a CH-47 helicopter.

- Last June, two Air National Guard C-130s flew to Guam, picked up a Marine Corps High-Mobility Artillery Rocket System [HIMARS] rocket launcher, and took it to another base for a simulated firing exercise before reloading it and returning to Guam.

- Senior Master Sgt. Brent Kenny of the 52nd Fighter Wing created a system using solar fabric and an environmental water harvester to produce drinking water, negating the need for pallets of prepackaged water and saving precious cargo space.

Training & Exercising Agility

Such ACE concepts and others will be tested at “Mobility Guardian 23,” AMC’s premier annual exercise, which will shift from the continental U.S. to the Pacific next year. The need for rigorous training and regular exercises to identify capability gaps and flaws in new concepts is another lesson standing out from early ACE doctrine development. Whenever possible, training events and exercises will be joint service and include international allies to better reflect how the Air Force will fight in a real-world scenario.

Training and exercise regimes “that are really tough” must be created, to teach enlisted leaders “to take prudent risks and not be afraid of making mistakes,” said Storms. “Debriefs also need to be timely and accurate in order to ensure we learn from the mistakes we do make,” he said.

Partners and allies need to be included in exercises, both to acquaint them with the considerable operational demands of ACE. Joint exercises will also underscore to potential adversaries that allies remain an asymmetrical advantage for the U.S.

Gen. Jacqueline D. Van Ovost, commander of U.S. Transportation Command, sees lessons from the Afghanistan experience, “because we were faulted for our ability to ‘scale quickly’ and eventually had to abandon some of our processes,” which slowed down operations.

“We also could not have accomplished that mission without allies granting us overflight rights, which we will need in spades in the Indo-Pacific,” she said.

Lt. Gen. Michael A. Loh, director of the Air Guard, pointed to lessons learned from the Afghanistan noncombatant evacuation, the largest in U.S. history. During the operation, one of the Guard’s C-17 crews landed at Kabul airport, taking fire. While the need to complete the mission and relaunch was urgent, the aircrew had no time to ask permission to abandon standard operating procedure.

“The loadmaster took … calculated risks, and in just 55 minutes, he unloaded cargo that would normally take four hours to offload,” said Loh. When asked how he did it, the loadmaster told Loh, “‘you don’t want to know,’” but Loh insisted, to ensure that no one in the chain of command will “stifle that kind of ingenuity.” While the Afghan evacuation was kind of “the ‘Wild West’ … that is the culture we need to harness in the future.”

An Emphasis on People

By Greg Hadley

“People” issues that generate headlines—inflation, recruiting challenges and sexual assault, to name a few—were a main topic among Department of the Air Force leaders speaking at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference.

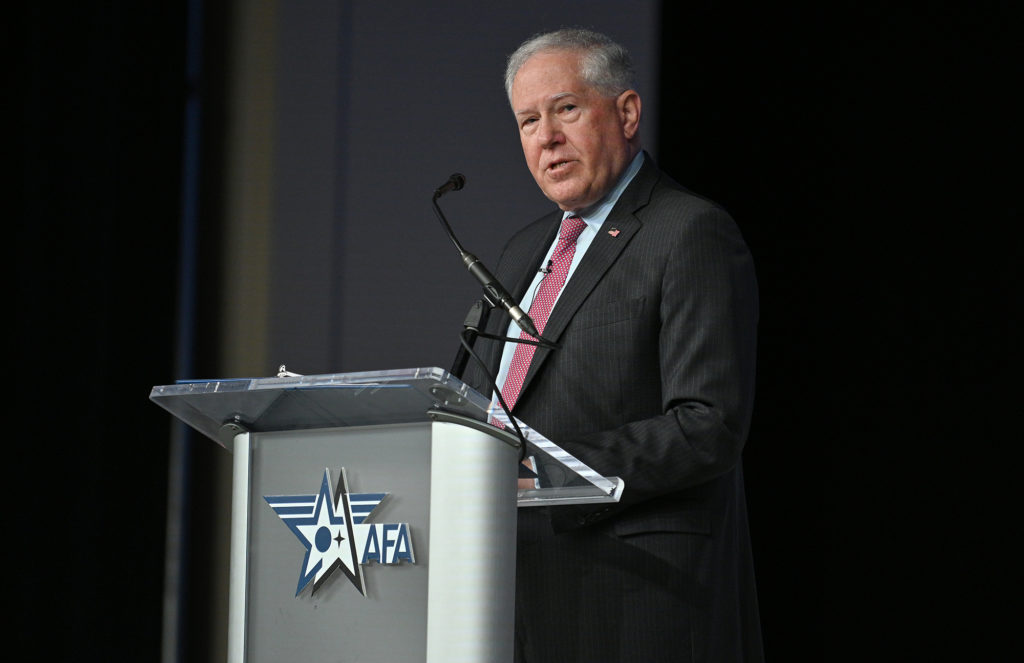

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall set the tone with his opening keynote speech, devoting roughly two-thirds of his 30-minute address to personnel issues like compensation, diversity programs, sexual assault prevention, child care, and housing.

Such a focus is needed, Kendall argued, to ensure the Department of the Air Force (DAF) is ready to compete with near-peers China and Russia.

Though he is known as “a technocrat,” Kendall said, he must put people first, because “it all comes back to mission and our readiness to perform it.”

“If you think that calling our Airmen and Guardians our decisive national advantage is just a tagline, take a look at what’s happening in Ukraine,” he said. “We’re seeing the price Russia is paying for failing to invest in its people. We’re seeing failure at scale in action, and it is very visible on the battlefield.” All DAF leaders took time to lay out a raft of policy changes and shifting focus.

Compensation

Kendall identified three main areas where personnel have expressed concerns: compensation, housing costs or conditions, and child care.

“The DAF leadership knows we can’t expect Airmen and Guardians to give their all to the mission when they are worried about paying for gas to get to work, finding child care, and providing their family a safe place to live,” Kendall said. “That starts with compensation.”

Compensation has been affected by record-high inflation, though. Service members are slated in 2023 for one of their biggest pay raises in decades, but it could be swallowed up by rising costs if current inflation rates persist.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has had to make ends meet to rising expenses like the cost of fuel.

With costly modernization programs to pay for, DAF made a controversial cut in its 2023 budget to reduce special duty pay for many communities of Airmen. This pay, which ranges from $75 to $450 per month, incentivizes Airmen and Guardians to stick with difficult duties that may involve an unusual degree of responsibility or a military skill in short supply.

But Kendall announced he was reversing that cut, saying the system had been “out of sync with the rapid changes to our economy.”

Leaders also acknowledged they have to address rapid economic changes affecting things like Basic Allowance for Housing (BAH) and Basic Allowance for Subsistence. Those allowances are set to get bumps in fiscal 2023, but again, inflation may erode them.

The Pentagon’s ability to respond to inflationary pressures is somewhat limited—typically, allowances are adjusted on a year-by-year basis. In September 2021, the Defense Department announced a temporary increase in BAH to help troops in certain markets, followed by another temporary increase for a smaller group of markets in September 2022.

Chief Master Sgt. of the Air Force JoAnne S. Bass has called for the Pentagon to craft a faster, more responsive method for adjusting BAH, and in a panel on community relations, Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. indicated he also wanted a change.

He’s looking for ways “to be a bit more responsive on some of our allowances to match up with what the economy is doing,” he said. He also doesn’t want Airmen to endure “a roller coaster ride” of wide swings, when inflation bears down or eases up, driving unpredictable changes in compensation, “So as a family, you can actually … build a budget.” Airmen should have a firm idea of “what your paycheck is going to look” every month.

In addition to allowances, Kendall and others all stressed the importance of providing better child care options for Airmen and Guardians.

Brown and Chief Master Sgt. of the Space Force Roger A. Towberman both noted issues that can leave families scrambling for childcare options because the DAF’s system is too slow or complicated; a fact Towberman highlighted with a slide showing that there are fewer steps a service member must follow to get childcare than those needed to quit the service.

“We live in the one-click world, and we must be retention-focused,” he said.

“The technical expertise, the depth of experience, the phenomenal craftsmen that we need to stay ahead of China and to win cannot be built in six months or a year, or in four years.” That requires that DAF give no one a reason to quit. “It can’t be easier to leave than it is to get help.”

Assignments

Leaders also laid out new policies aimed at giving Airmen and Guardians more options and flexibility in their careers.

Bass announced a slate of changes on how the Air Force handles assignments, based on recommendations from the Enlisted Assignment Working Group. Among them were switches to assignment priority posts for military training instructors, military training leaders, and recruiters; no more time-on-station requirements for expedited transfers, and no ‘report no-later-than dates’ for four months for Airmen returning from deployments.

Perhaps the biggest change Bass previewed is a new assignment swap policy, which could allow Airmen to switch jobs and locations if they can find someone with a similar specialty and skill level.

“There’s a whole lot more coming,” she said.

Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond touted the service’s focus on specialized skillsets for Guardians, allowing assignments to be more tailored.

“It’s no longer good enough to say, ‘Hey, I need a lieutenant colonel space operator, or a master sergeant space operator,” he explained. Now, it’s “we wanted a lieutenant colonel or master sergeant with orbital warfare…[and] technical skills…for example, data management skills.” By doing this for every billet, “we could be more purposeful in our assignment process.”

Towberman went further, saying “the entire environment is tailorable,” so that while the Space Force has focused on specialized assignments, it has opened up its leadership opportunities.

“On the enlisted side, we don’t have … key leadership positions anymore. We don’t have stratifications anymore,” he said. “We’re doing all we can to eliminate anything that could be used as a proxy for truth … [things] we should be able to learn and know about a human being if we look hard enough.”

Recruiting

While Towberman preached the importance of retention, the services still need to recruit new talent as well. And while the USSF continues to have more than enough applicants, the Air Force is hitting an historically tough recruiting environment and only barely reached its Active-duty goals for fiscal 2022.

Both long-term and short-term issues affect the Air Force Recruiting Service, commander Maj. Gen. Edward W. Thomas Jr. told reporters. Among them are continued declines in both eligibility and propensity to serve among America’s youth, along with the cumulative effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and a competitive labor market.

Some of those short-term problems will resolve themselves over time, Thomas said. But for the bigger picture issues, the Air Force’s recruiting enterprise is taking a proactive approach.

That includes expanding the pool of eligible recruits: Pentagon surveys have shown that just 23 percent of the target population is eligible due to issues such as medical conditions, prior drug use, out-of-regulation tattoos, and trouble with the law.

He insisted that he has no intention of compromising on standards, but Thomas outlined several ways that eligibility can be expanded.

“A year or two ago, frankly, we could afford to lose people around the margins because of finger tattoos, [or] because of certain medical conditions that we weren’t willing to take risk on,” Thomas said. “We are in an environment today that we have to be exceptionally smart in how we assess the risk and how we set our accession criteria.”

Recently, Thomas was granted the authority to approve waivers for smaller hand tattoos, a process he’s done hundreds of times using photos on his iPhone.

It’s a process he’d like to shed. He’s advocating for a change in policy to reflect changing societal attitudes toward tattoos.

Another issue that has seen a shift in public opinion is marijuana use. As more and more states legalize cannabis, either for recreational or medicinal use, the Air Force is also taking steps to ensure it isn’t automatically disqualifying for a recruit, while at the same time emphasizing that “drug use … has no place” in the Air Force.

A new policy allows recruiters the latitude to let recruits retake their drug test if they come up positive at the Military Entrance Processing Station (MEPS), and it’s determined to be due to unintentional exposure or residual effects, Thomas said.

“This is not about … those folks who were not honest with their recruiter, and they smoked marijuana…and the next day or … week, they went to MEPS and they tested positive. That’s not who this is for,” he noted.

Recruiters are also looking to leverage more data when it comes to approving recruits with medical conditions that previously would have been automatically disqualifying.

“For instance, … if you look at issues like mental health conditions, anxiety, eczema, asthma … we’ve been able to turn up the dial” on who will be granted a waiver, decreasing the disqualifying rate “by 30 percent or more in some of those categories, simply by having the data” to better assess potential impacts, Thomas explained.

In addition to expanding the overall recruiting pool, Air Force and Space Force leaders also emphasized continued efforts to attract a more diverse cohort of Airmen and Guardians, an effort Thomas said will not affect standards but is necessary to solve the “mathematical” problem of an increasingly diverse general population.

More immediately, Undersecretary Gina Ortiz Jones said, a more “deliberate” approach to recruiting diverse candidates will increase mission readiness.

She said, “We recently had a meeting at the department, where we were talking about our competition for strategic talent. And the last time we had looked at our talent pool and our goals … with regard to some critical languages was in 2004. That was a long time ago. … That was Baghdad times. We’re in Beijing times.”

The critical talent pool with respect to these language skills “did not reflect essentially what we needed,” she said, driving a rethink of requirements—as well as being “deliberate about bringing in that talent.”

It takes about six to eight years to develop a Chinese linguist at the “three-three level,” she noted.

“That’s a long time. That’s time we don’t have. You know who can probably get to three-three, if they’re not already at a three-three, much quicker? Chinese Americans; first-generation kids” who may see that one or two hitches in the Department of the Air Force “might be something that is attractive for them and something that they may consider, had they not previously.”

Flexibility for the Air Force Future

By Chris Gordon

New capabilities like hypersonic missiles, B-21 bombers, and other cutting-edge weapon systems are key to the Department of the Air Force’s future. But it must also have the flexibility to make the most of what it already has, top leaders said at AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference on Sept. 19-21.

Among the marquee initiatives in making old USAF systems capable of new tricks include turning cargo planes into weapons launchers, training “multi-capable” Airmen to double up on their skills, dispersing aircraft to expeditionary bases, and working more effectively with allies.

“The Air Force was founded on a different way of looking at things,” said Gen. Mike Minihan, the head of Air Mobility Command and the former deputy commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command (USINDOPACOM). The service must “make sure we’re doing everything possible to use what we have in the most efficient and effective manner.”

The initiatives are diverse. Under the Rapid Dragon program, the Air Force is experimenting with dropping palletized munitions out the back of cargo planes such as the C-130 and C-17. Crated onto wooden pallets, AGM-158B Joint Air-to-Surface Standoff Missile-Extended Range (JASSM-ER) missiles fall out of the aircraft, are extracted from the pallet by parachute or gravity, ignite their engines, and head off to their targets. The idea is to add mass and unpredictability to the force. A live-fire test has been successfully conducted.

There is a strategic rationale for the innovation: While the service is waiting for future stealthy aircraft such as the Next-Generation Air Dominance program and the B-21 bomber, it will have fewer aircraft that can operate in harm’s way. Many of America’s air bases are within missile range of its main adversaries. As a result, the Air Force must be able to function from “austere environments,” or nontraditional air bases. While logistical challenges remain, they are made easier when rugged, lower-cost aircraft like the C-130 can be used as a strike platform.

“A C-130 only needs about 3,000 feet of dirt or straight stretch of road or whatever to generate sorties, which provides a complicated problem for our adversaries that might want to target our infrastructure,” Lt. Gen. James. C. “Jim” Slife, head of Air Force Special Operations Command (AFSOC) said. The C-17 also has short runway capability. Current tests are working toward six weapon configurations for the C-130 and nine weapon configurations for the C-17, with the possibility to expand that in the future.

“Why would I drop a pallet of JASSMs out of C-130?” Minihan asked rhetorically. “Frankly, I don’t want to take the time to land, download it, have it find the army maneuvering unit, upload it. And that tempo is going to be the tempo required to win.”

Slife said the service is learning to get past its “prefixes.” Airplanes with a “C” prefixes “carry cargo. What do we do with ‘B’ airplanes? We drop bombs,” he said. But, “the reality is, they’re all just airplanes” and can be used in many ways. The KC-46 tanker, for example, will be pressed into service as a communications node in the sky; there’s room on board, and it will already be in the area where “combat” aircraft will be working.

AFSOC also wants to test an amphibious modification on its MC-130s, fitting the aircraft with massive pontoons and thus expanding potential landing sites when a flat runway-like field isn’t handy. This capability would be especially useful in the Pacific, Slife noted.

With an amphibious MC-130J program, the Air Force is testing the ability to bypass the need to land at all—at least on a runway. However, that would be a niche capability set aside for AFSOC.

Air Force Chief of Staff Charles Q. Brown Jr. said the service is still exploring how much adapting existing aircraft to new roles would be “a complete part of the Air Force.”

Still, complicating enemy targeting—and imposing cost on the adversary—is an attractive option.”It’s the multi-capability of a platform to provide us the opportunity, budget resourcing or not,” Brown said. “They’ve got to account for these things.”

While putting cruise missiles on cargo planes may expand the number of targets an enemy must go after, the Air Force would still need to buy the weapons. In the case of the JASSM and JASSM-ER, the cost is upward of $1 million per missile.

“If … we start buying significant numbers of standoff weapons, I think it can really make an important contribution to denying the enemy invasion,” said David A. Ochmanek, a senior researcher at the Rand Corp., former senior Defense Department official, and U.S. Air Force Academy graduate.

Another innovation, which the Air Force has already put into effect, is ending the practice of continuously basing bombers in Guam and instead flying Bomber Task Forces to critical regions from bases in the United States. The endeavor is intended to make U.S. bomber deployments less predictable, and to provide military leaders with more flexibility in deploying nuclear-capable B-52s, stealthy B-2s, and B-1s. For example, as tensions soared during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the iconic B-52 flew missions over Europe, along with allied F-35 stealth fighters, pairing one of the oldest deterrents with one of the newest.

Other moves to provide the Air Force with more flexibility are still evolving, including the Agile Combat Employment (ACE) concept that is intended to enable the Air Force to disperse its aircraft to a wider array of bases, some of them expeditionary, and the plan to train multi-capable Airmen to reduce the U.S. military’s footprint.

Yet another way to ease the burden on the existing U.S. forces is to rely even more on America’s allies and partners. In Europe, Sweden and Finland are set to join NATO, bringing with them capable air forces. Finland has 64 F-35s on order. Sweden has a homegrown aircraft industry, which the U.S. Air Force has already turned to for a significant portion of its new T-7 trainers. The Swedish government also dedicated money to a project towards advancing its fighter designs after committing to join NATO. In the meantime, Sweden is procuring 60 of the latest E variants of its Gripen fighter.

The U.S. Air Force has stepped up exercises with its allies in Europe as other countries share more of the air power burden, reported Gen. James B. Hecker, commander of both United States Air Forces in Europe–Air Forces Africa and NATO’s Allied Air Command.

America’s allies plan to bolster their air forces, NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg said.

“I think that willingness to invest, to spend money in difficult times shows that the political leadership realizes what you do really makes a difference and is more important than it has been for many, many years,” Stoltenberg told staff at Allied Air Command in September.

America’s allies in the Indo-Pacific are also increasing their defense spending in response to a changing world.

Taiwan, directly threatened by China, is set to massively boost its defense spending by nearly 14 percent in 2023. Australia signed a defense partnership with the United Kingdom and the U.S., abbreviated to AUKUS, that will enable it to field its own nuclear-powered submarines for the first time. It also includes partnerships in other areas, including artificial intelligence, autonomous systems, hypersonic missiles, and undersea technologies, among other areas. Japan, whose public has long resisted non-domestic defense activities since World War II, aims to double its defense spending to 2 percent of gross domestic product within five years. In addition, Japan is working on developing its first-ever indigenously produced stealth fighter for the Japan Air Self-Defense Force.

“When you’re operating in a tough neighborhood, travel with friends who know how to fight,” said Gen. Mark D. Kelly, head of Air Combat Command.

To make the most of the U.S. alliances, the Air Force needs to bring its allies into planning and development at every stage. “They’re more likely to buy into something if they felt like a part of the process,” Brown said. Even the idea of deploying palletized munitions has been proposed as a way for partners to boost their firepower.

Some experts caution that flexibility initiatives like ACE, while worthy, do not eliminate the need to pursue more far-reaching efforts to develop new weapons systems, command and control, and operational concepts to deal with the growing threat from China and Russia.

“We’re faced with an enemy that’s confronting us with challenges that, at least for the Air Force, are almost existential in nature,” said Ochmanek. “What I’m hearing about flexibility is we’re kind of tinkering at the margins to try and mitigate those challenges. But we’re not solving them with this approach.”

The Air Force says that preparing for Chinese and Russian challenges will require adaptation after two decades of flying in uncontested skies from secure bases to fight against ill-equipped extremists in the Middle East and Southwest Asia. The service wants to create a culture of innovation. If so, the best time for test runs is before the shooting starts.

“I’d rather explore some of these opportunities when we’re not in conflict versus trying to do it all in conflict,” Brown said.

Advancing Toward the New Collaborative Combat Aircraft

By John A. Tirpak

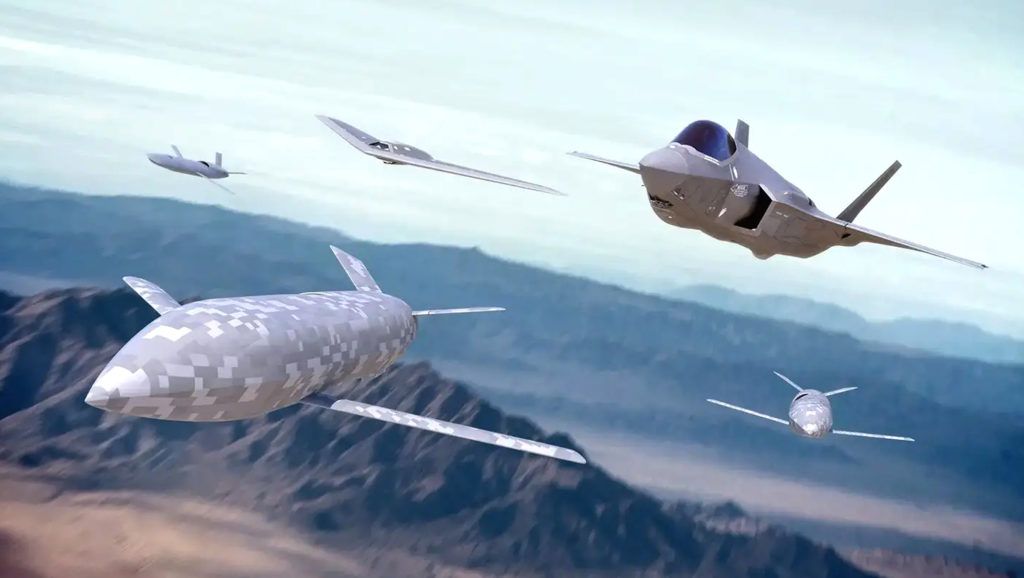

The Air Force wants to develop and build a large number of uncrewed airplanes to build capacity, augment the existing fighter fleet, and impose costs on a potential enemy. But how it will go about developing and introducing what are now known as Collaborative Combat Aircraft (CCA), and the form they’ll take, is still very much a matter of discussion and debate.

Air Force leaders at the 2022 AFA Air, Space & Cyber Conference saw a wide diversity of proposed CCAs at contractor booths in the exhibit hall. Ever since Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall named CCAs one of his seven “operational imperatives” the service must field to deter China, the Gold Rush has been on to meet the Air Force’s need.

But service leaders have so far not bounded what a CCA will be; only that the Air Force must start testing them in the next couple of years, and have them in the force in meaningful numbers by the end of the decade.

Industry has put forward ideas ranging from inexpensive, controllable aircraft that are only slightly more sophisticated than expendable missiles, all the way up to highly sophisticated, stealthy platforms that could fly well ahead of the main fleet, collecting information, suppressing defenses and acting as pathfinders.

Kendall told reporters in a press conference that in the Operational Imperatives, “I defined the problems that we’re trying to solve, and that gave industry some information that they can use to make their own investments. And I think they’ve reacted to that … not just parroting back” he said, but “bringing forward some innovative ideas that we certainly want to consider. I’m encouraged by that.”

He’s also admonished industry “repeatedly…[that] I don’t want you waiting for the RFP to come out. … If we adopt your solution to our problems, that probably gives you a head start. It’s in your interest to be thinking ahead of us and giving us creative ideas.”

As the concept now stands, he explained, a crewed fighter, “whether it’s NGAD [the Next-Generation Air Dominance system] or possibly the F-35 or even the F-15EX—is going to be accompanied by, let’s say one to five uncrewed aircraft … that the manned aircraft will control.” The crewed fighters will be “the quarterback, or play-caller for that formation.” The uncrewed airplanes will have “a variety of mission systems and sensors, including weapons. And you can employ them in very creative ways.”

This sets “a very difficult problem for the adversary,” Kendall said. “He has to regard every single one of those platforms as equally a threat. And so, he can’t neglect any of them.” The CCAs also offer a clean slate to write new air combat tactics, Kendall noted.

“So, we have a lot to work our way through to develop this and field it. And there are a lot of unknown questions about how far we can go.”

He said he’s got the Air Force Scientific Advisor Board “working on the task of what we should shoot for, in our first substantiation of the kind of concept I just described. And I think we can go pretty far.”

What Kendall doesn’t want to do is “over-reach with the first ones,” but rather to try to field something quickly, with more sophistication possibly coming later. But “we want it to be very cost-effective,” he said.

“You can get big operational exchange advantages … and cost-effectiveness advantages out of this concept. Our analysis shows that’s definitely true. And the technology is there to support it.”

He has previously said that most of the Operational Imperatives were based on rapidly maturing technologies in development with the Air Force Research Laboratory. The CCA idea is possible because AFRL has nurtured its Skyborg airplane-flying, artificial intelligence system to an advanced point.

Gina Ortiz-Jones, undersecretary of the Air Force, emphasized to reporters that “we’re not talking about less pilots” in the service. “We’re talking about a different way that we employ CCAs that augment the capabilities that we currently have.”

Andrew Hunter, an Air Force acquisition executive, told reporters that “given the timelines that we’re working on …the first thing is to field something meaningful in the next several years, due to the threat. So that’s absolutely going to be the early focus.”

Hunter said the Air Force isn’t necessarily looking at multiple types of CCA platforms.

“It’s more about accomplishing the mission,” he said. The CCA might be a single platform with modular elements, or “it may be the case that there may be multiple platforms. And that’s something we’ll figure out over time. We’ll work with industry to identify what is the most effective mix of vehicles and mission systems.” Mission systems, he said, are “a big part of the puzzle.”

There are likely to be “iterations” of the system, Hunter said. “But the highest priority is to field a capable CCA that can team with our manned platforms in the earliest time frame” possible.

Funding for basic work will come in the fiscal 2024 budget, Hunter said, moving toward fielding “in the ’24 POM,” or program objective memoranda, a five-year plan.

The idea for CCAs came out of the NGAD program which will need to function as a family of systems, he said, and that in turn requires “operating in denied airspace and making sure we have the ability to establish freedom of action, freedom of maneuver for U.S. forces.” Inherent to that is survivability and ability to communicate back to friendly forces, but Hunter would not comment on “how exactly CCA will do that.”

“Also, there’s the issue of scale,” he said. “A lot of the things that are out there aren’t necessarily … production (ready).”

But “I want to foot-stomp: this is an acquisition program,” Hunter said. The Air Force may not use “other transactional authorities” of the kinds that have been used in recent years to accelerate programs. Such “OTAs” are typically “about prototypes [and] experimentation,” Hunter said.

“We will choose our [acquisition] tool sets to be aligned” with the objective of developing and fielding “on a near-term timeline.”

Hunter said the Air Force is “open” to collaborating with allies and partners on such systems, but if they are to be fielded in numbers, the system will have to comply with laws requiring certain levels of U.S. content, and be built in the U.S.

“There is an implicit competition” already underway, Hunter said. “All the main players are aware of that, and I am confident we will be able to field something in a very relevant time frame,” he said.

Given that CCAs come out of Kendall’s operational imperative, and that requirements usually come from a user command, Hunter was asked if Air Combat Command is being handed a requirement, top-down.

“The requirements community was an integral part” of creating the operational imperatives, Hunter answered. “So, I would say that, as far as I can tell, we have very strong buy-in from the requirements community, [and] from ACC , as to the need for a CCA, the utility of a CCA, and continuous input on exactly what kinds of missions CCAs can perform.” He added that “we remain engaged continuously” with the user on requirements.

He acknowledged, though, that there is “cultural resistance” to CCAs.

“There has been cultural resistance to uncrewed aircraft as long as there have been uncrewed aircraft,” Hunter asserted. “Some of this is human nature. Change is hard. It is in every aspect of our business.”

That requires strong top-down, “strong leadership support to overcome the cultural barriers that are sometimes there when it comes to uncrewed aircraft.”

He said there’s such support from Kendall, from Chief of Staff Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. and from ACC’s Commander, Gen. Mark D. Kelly. “And we need that.”

Gen. Duke Z. Richardson, head of Air Force Materiel Command, told reporters that “we know through modeling and simulation that there’s value in teaming crewed and uncrewed aircraft. So the question becomes, what do the numbers look like, and what does the mission package look like? That work is not yet completed.”

In his opinion, “I think it’s multiple mission packages. I don’t think it’s going to be just one thing,” but it’s possible CCAs may be a single airframe with modular mission packages.

A certainty is that the CCA will be built with “digital engineering, agile software development, [and] open systems architecture. CCA will be founded on that.”

There’s no question that CCAs are coming, and will be a big part of the future Air Force, Kelly said.

“Everyone is in agreement” about that, he told reporters at the conference.

What he’s concerned about is that USAF may rush to field such systems and may in the process get the concept wrong and have to go back start again. He’s advocating a building block, iterative approach to fielding the aircraft, with each step defined by aircrews actually working with prototypes and lending their ideas and experience to the process.

“The captains will lead us in this,” Kelly said, referring to the Weapons School experts and veterans of Red Flag exercises. He wants to “get the tools to the Airman and get out of their way. Let them iterate and innovate.”

Each iteration should be inserted “into the mix,”—and the lessons learned—he said, adding that he’s certain “if we try to foist this” on combat pilots “and tell them how to do it, we’ll mess this up.” Rather than “swing for the fence” and quickly develop what he called an “exquisite” capability, the Air Force should “get some singles and folks on base and try to iterate our way there.” He doesn’t want “an exquisite miss,” partly because “exquisite means exquisite pricing.”

He also said the CCA has to be developed in lockstep with the all-domain command and control system and communications that can work in denied airspace through heavy jamming.

“I could have a CCA that could punch into really, really highly defended … airspace, but if I don’t have resilient comms, and that thing doesn’t know how to phone home … I don’t get it home.”

He also noted that uncrewed, armed aircraft can only operate from a few Air Force bases nationwide that are immediately adjacent to restricted airspace; they are not yet FAA-cleared to operate in regular airspace, and that’s a hindrance to developing a useful capability.

“You can race down the track of autonomy,” Kelly said, but if the authority to operate unrestricted doesn’t come with the hardware, the concept will fail.

“I’ve got to have autonomy, authority, and resilient comms” if CCAs are to be a success, Kelly said.

Companies looking toward a “clean sheet” CCA should emphasize iteration and modularity, he said, with interchangeable sensors, jammers, and other mission items. Operators should be able to “unlock a nose, bolt on another nose … quickly take off the radars, put on the jammers.”

He urged contractors not to “lock it in” to a particular mission.

“If we lock ourselves into” a particular mission or capability, the CCA could be a “race to failure,” he warned.

If the Air Force guesses wrong, “we have to go back to the start,” costing money and time the Air Force can’t afford to waste.

Nevertheless, he agrees with Kendall that it’s time to “get past the PowerPoint slides” and start producing something.

“He’s right, there’s enough out there that we can start iterating now.”

Kendall said, “I’m convinced that we should move in this direction, and we’re going to do it, under any budgetary future that I can imagine.”

The Story Behind the Space Force’s New Official Song

By Amanda Miller

James Teachenor was living in Nashville in 2015 and browsing Craigslist for vintage guitars when he spotted the unlikely ad that led to his occupying a unique place in military history.

The Air Force Academy’s country band Wild Blue Country needed a lead vocalist. Teachenor later found out the ad was only up for a matter of hours.

“It wasn’t supposed to be advertised that way,” he recalled while headed back home to Nashville from AFA’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference with his wife and two teenage kids. “For whatever reason, I saw it in that small amount of time, and I called Colorado Springs and asked if it was legitimate.”

After a few more questions, “I put Colorado Springs’ weather on my phone, because I knew we were going to Colorado Springs,” he recalled. Without having yet auditioned, “I knew that was part of my path.”

He became a senior Airman with the band, which performed at events for both the Air Force Academy and what was then Peterson Air Force Base, Colo., home to the Space Force’s predecessor, Air Force Space Command.

Given that this frequently put him in contact with military space personnel, it’s hard to imagine anyone better positioned to supply the words and melody to the Space Force’s new official song, “Semper Supra,” which debuted at the conference.

Together with a Coast Guard trombonist who doubles as musical arranger, Teachenor composed ‘Semper Supra’ to join the likes of the Air Force’s “U.S. Air Force”—aka “Wild Blue Yonder.”

“What was very interesting about my time of service was I knew what the space capabilities were for space operators before they were Guardians,” Teachenor said. He also met today’s Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond and Chief Master Sergeant of the Space Force Roger A. Towberman at that time. As Teachenor’s enlistment wound down in 2019, he even went along on a trip with the two leaders to Thule Air Base in Greenland, which performs missions in space surveillance and missile defense.

“I got to see so much of what our now-Guardians—but at the time they were Airmen—do and just was blown away by their mission,” Teachenor said. He felt like the trip “had a lot to do with how the song was written because I saw firsthand just the precision and the … amazing assets that we have in our folks who wear the uniform. And our civilians, too.”

Teachenor and his family went back to Nashville following the conclusion of his enlistment, and in December 2019, the Space Force came to be.

“Several folks reached out and said, ‘Hey, you know, the Space Force is actually going to be a branch—are you thinking about writing a song?’”

He didn’t laugh off the idea but “eventually General Raymond and Chief Towberman reached out to me and said, ‘Hey, would you consider writing something and just, you know, give us an option?’”

Feeling simply “honored and thankful just to even throw something in there,” Teachenor estimated that by about February 2020, the song was largely complete.

“I knew they wanted something that was singable and that fit with the other anthems—the other service songs—and that would be something that could last. … They made it very clear they wanted it to be timeless.”

Months passed as the service narrowed down the submissions until choosing Teachenor’s.

Throughout the process, Space Force leaders made only one request, he said—to include the words “standing guard both night and day,” and to emphasize the service’s continuous mission of “making sure that we’re safe and protected all the time.”

“And so I looked at that line and changed it. I believe it’s a better line for that,” said the recently elected county commissioner for Sumner County, Tenn.

The Score

Trombonist and arranger Coast Guard Chief Musician Sean Nelson responded to a callout to military band arrangers early in the Space Force’s search for a song. Now an 11-year member of the U.S. Coast Guard Band based at the Coast Guard Academy in New London, Conn., he’d been “a little green,” he said, when he originally auditioned for the Air Force Band in the competitive national auditions that draw high-caliber musicians who ultimately “come in fully trained for the job.”

He’d composed the score to an organization’s military-style service song once before, updating the march of the Commissioned Officer Corps of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

By 2020, he’d made a submission to the Space Force based on a preliminary set of lyrics, and “the group listening really liked my version.” In the spring of 2022, “they contacted me again and said, ‘We’ve come up with this melody and lyrics’—and it was Jamie’s lyrics and Jamie’s melody—‘and we’re looking for somebody to complete the song, to harmonize it, to orchestrate it.’”

Nelson liked the lack of any other musical contribution such as a chord structure “because it allowed me to be creative with it.”

“What I would do is I would play the melody on the piano, and I would sing it, and I would keep trying different harmonies underneath it. And sometimes there’s harmony that is obvious, and sometimes there’s harmony that makes sense but is unexpected,” said Nelson.

He would ultimately compose 30 parts for a full military band, from the four-part vocal harmony performed at the Sept. 20 premiere by the Air Force’s Singing Sergeants to counter-melodies—“there’s the main melody that you sing, and there are multiple melodies going on at the same time above and below that melody that makes it sound full and thick and [gives it] a traditional march sound.”

Having performed the “Armed Forces Medley” of service songs at many military events, he well knew the need for the Space Force’s to fit in with the other traditional military marches. At the same time, he wanted to write something “that was maybe a little unexpected and maybe not as obvious and that had its own sounds as opposed to copying other military songs.”

To strike the balance, “you have to know the tradition”—specifically that of American march composer John Philip Sousa—“while knowing where you can break from it.”

Without such a well-trained ear, “not everyone might notice it,” Nelson said, “but I think if you listen to it a few times, you start to notice, ‘Hey, that sounds a little fresh.’”

He sang the first two lines to demonstrate:

“We’re the mighty watchful eye; Guardians above the blue. …

“When you get to the word ‘blue,’ that chord is outside of the key—so it’s just a little bit surprising, I think. … Maybe you get a little extra sparkle out of it.”

Nelson suspects—based on his experience performing in the Coast Guard Band, usually without singers—that “the form that you’re going to hear the song in the most is actually going to be without singing.”

Next he expects the military bands—along with school bands and choruses across the U.S.—to start adding “Semper Supra” to their medleys.

“Semper Supra”

We’re the mighty watchful eye

Guardians beyond the blue

The invisible front line

Warfighters brave and true

Boldly reaching into space

There’s no limit to our sky

Standing guard both night day

We’re the Space Force from on high

Beyond the blue

The U.S. Space Force.