AMC and PACAF say they have overcome fuel storage and aerial refueling concerns.

JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM, Hawaii and ANDERSEN AIR FORCE BASE, Guam

Rust-tinged, white fuel storage tanks dot the coral plateau at Andersen Air Force Base, Guam. Jet fuel pumped up through a 26-mile pipeline from the Port of Guam fills the tank farm, the largest in the Air Force at 66 million gallons of capacity. It’s why Airmen call Guam “the gas station of the Pacific.”

Across sites in the vicinity of Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam on Oahu, Hawaii, another 250 million gallons of fuel capacity sits underground and in large aboveground tanks that glow white before the deep green Hawaiian mountains.

That’s a lot of fuel. But experts say its not enough to support aerial refueling in the Pacific.

Defense analysts worry about Air Force plans to reduce its tanker fleet, coupled with limited fuel storage capacity in the Pacific, posing risks to U.S. military readiness. They worry Air Mobility Command (AMC)will be unable to meet demand should the U.S. face a war with China.

It takes fuel to be able to move around the Pacific, and you’ve got to have that fuel in the air.

PACAF Commander Gen. Kenneth Wilsbach

The anticipated retirement of the Air Force’s 48 KC-10 Extenders by fiscal 2025 will create a 13 percent shortfall in tanker capacity versus potential demand, according to a report of fully operational aircraft by the Hudson Institute. In addition, the Air Force plans to retire 13 KC-135 Stratotankers in fiscal 2023. Meanwhile, the new KC-46 Pegasus fleet is still working through problems with its remote vision system (RVS). The Air Force had 29 KC-46As in the inventory at the start of fiscal 2022 and 61 as of June 17, 2022. It anticipates having 14 more by Oct. 1, 2023. By Oct. 1, 2025, the Air Force expects delivery of a total of 119 KC-46s.

Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall is pursuing a “divest to invest” strategy, giving up aircraft that are less useful and more expensive to operate now in order to devote more resources to fund future capabilities.

As of September 2021, the Air Force tanker fleet stood at 490 planes, consisting of 392 KC-135s, 50 KC-10s, and 48 KC-46s. The 2019 National Defense Authorization Act calls for a minimum of 479 tankers. But Kendall wants to reduce that floor number to as few as 455 and the House version of the fiscal 2023 authorization bill would allow the Air Force to end the year with as few as 466.

Air Mobility Command admits that studies to date have shown that limits to refueling capacity are based on the number of tankers available, not their fuel-carrying capacity or offload rate.

The KC-46 is capable of carrying approximately 212,000 lbs of fuel; the KC-135 can carry 199,000 lbs of fuel; and the KC-10 can carry 356,000 lbs of fuel. AMC calls the debate the “booms in the air” vs. “gas in the air” discussion.

“The total number of tankers available to fight is the main driver of capability, regardless of what type of tanker they are,” AMC said in a statement. “That being said, the KC-46 will be a fundamentally more capable tanker than anything we’ve fielded once the platform reaches [full operational capability].”

AMC said fixes tied to the RVS and the Boom Telescope Actuator Redesign, known as “Stiff Boom,” are required for the Air Force to declare full operational capability and fully commit the KC-46A to support combatant command requirements. Current Boeing schedules show both upgrades delivering in FY24.

Either way, AMC believes the ICRs have closed any perceived tanker gap, and that 455 tankers provides enough capacity to meet historic TRANSCOM daily tasking levels and wartime demands, should they occur.

Easy Fixes: More Fuel Storage

Timothy A. Walton co-authored the November 2021 study on aerial refueling for the Hudson Institute, concluding the risks are growing in the Pacific.

“If we’re faced against a major power like China, we’ll probably need 479 or more,” Walton told Air Force Magazine in June. “You need numerous tankers in order to be able to geographically and temporally distribute your forces. That’s going to be a very difficult decision for the Air Force as to whether it’s prudent to go down to 455.”

Walton admitted that an updated analysis with KC-46 clearance rates above 90 percent does reduce the refueler gap.

“The bigger issue is not the mission capable tanker fuel offload capacity, but rather the Air Force proposal to cut the fleet to a required 455,” he said. “There are likely already major capacity gaps at 479 in relevant scenarios and further drops will be problematic, even if there are then more crews to maintain higher surge rates for the 455 aircraft.”

Walton said the fiscal 2023 budget does not get after the problem.

“In the latest budget request, I haven’t seen any significant changes either in posture, or in the aerial refueling force, that would enhance our ability to support operations at distance throughout the Indo-Pacific,” he said. “We need to evolve our posture in the Indo-Pacific to make it more resilient.”

Walton sees bulk fuel storage as the best way to ease the capacity shortfall. “DOD needs to shift to adopt a more resilient approach to bulk fuel storage distribution posture,” he explained.

The problem was accentuated in March when age and poor maintenance of the underground Red Hill facility in Hawaii led to leaks and the DOD decision to defuel the site.

“We need to shift to something else,” Walton said. “We probably need some more distributed, hardened underground fuel storage, smaller capacity than Red Hill, but in more places; we need some complementary maritime tankers to be able to serve as pre-positioned floating gas stations and transport the fuel throughout the theater.”

The Defense Department said Pacific fuel storage will be compensated by land and afloat locations, but DOD did not provide a timeline for replacing the lost ground storage capacity.

In Fiscal 2023, the Air Force has asked for military construction funds to add aboveground fuel storage at the U.S. territory of Tinian, Guam’s neighbor to the north in the Northern Marianas Islands. The Defense Logistics Agency is adding a Defense Fuel Support Point in Darwin, Australia. Both sites will be aboveground, unhardened facilities.

“There are a number of options that could be taken more quickly to enhance our posture in the Marianas, and throughout the second island chain with other Compact of Free Association states,” Walton said, referring to the South Pacific states of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands, and Palau. “This is essential for us to address aerial refilling gaps.”

ACE in the Pacific

The boom operator on the new Boeing-built KC-46 sits upright at a control station with dials and switches and a joy stick to direct the boom, rather than lying facedown at the rear of the aircraft and looking out the back. A remote vision system and special 3D glasses helps him guide the boom to the receiving aircraft.

While flying along an aerial refueling track in upstate New York in July, boom operators who are part of the 2nd Air Refueling Squadron, 305th Air Mobility Wing at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, N.J., described how shadows and washout caused by the sun at certain times of day can make those final feet before a plug impossible to see clearly.

The booms said the problem arises both for low-backed fighter aircraft, like the Maryland Air Guard F-16s refueling that day, and large mobility aircraft.

Depth-perception distortions with the 3D image on the main 1080 pixel black-and-white screen also make performing an accurate plug more difficult. What’s more, when the boom operator turns a dial to change source cameras, there is a momentary blackout on the screen where the image of the boom and receiving aircraft briefly disappear. The Air Force has restricted the boom operator from flipping between camera views, called “scenes,” while the receiver is within 50 feet of the boom. That means the receiver aircraft must return astern, or reset, to 50 feet and approach again before the boom operator can switch scenes to a visual display that might offer better visibility for the lighting condition.

Refueling delays can range anywhere from five to 30 or more minutes, experienced boom operators from the 2nd ARS said.

Problems with the RVS are being fixed at Boeing’s expense and the resulting delays have contributed to the tanker shortfall, with no delivery date yet set for RVS 2.0.

Rex Jordan, a 20-year Air Force veteran who now is a senior vice president at Booz Allen Hamilton, said smoothly refueling combat aircraft is essential to America’s Pacific deterrence strategy.

“Refueling our fifth-generation fighters is of course going to be the key to success in the Pacific,” said Jordan, who leads the defense contractor’s Indo-Pacific business. A former navigator who became chief of presidential flight support before retiring from the Air Force, Jordan said the Air Force’s agile combat employment (ACE) strategy for operating in a more distributed fashion across the Pacific depends on ample and effective aerial refueling.

“F-35 and F-22 are really the key to employment, and employment requires that ability to aerial fuel,” he said by video conference from Honolulu. “So, that gap that starts to emerge between the divest to invest is going to be something that I know [PACAF Commander] General Wilsbach and others will be interested in making sure they fill.”

As of May, the KC-46 was cleared for 97 percent of taskings, but not yet for combat operations.

Retired Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, dean of AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies and director of air and space operations at PACAF from 2003 to 2005, said refueling is a huge issue.

“If a conflict erupts in the South China Sea area, that is going to take the entire U.S. Air Force tanker fleet to support. What do you do about the rest of the world?”

‘We’re in Pretty Good Shape’

Pacific Air Forces and Air Mobility Command leaders sat down for staff level talks June 22 to 23 at PACAF headquarters at Hickam to ensure they will be ready for whatever demand arises.

“We’re in pretty good shape on tankers,” Pacific Air Forces Commander Gen. Kenneth S. Wilsbach told Air Force Magazine during a June 9 interview in his Hawaii headquarters.

“We have a method to keep an immense amount of fuel in the air and fuel in the air allows us to project our power forward, and you don’t run out of gas and have to go land somewhere,” he said. “We’re in very good shape with tankers.”

Wilsbach went into further detail in March during the AFA Warfare Symposium.

“It takes fuel to be able to move around the Pacific and you’ve got to have that fuel in the air,” he said. “We’ve got to be able to have the tankers available, then be able to protect those tankers, because the adversary is trying to do long-range kill chains against our tankers and command and control aircraft.”

The Air Force has never dipped below 478 tankers, which it hit in 2009, according to historical data compiled by Air Force Magazine.

Over the past decade, the number of tankers flying daily has ranged between 200 at steady-state to 250 during surge operations. “The tanker enterprise can produce this USTRANSCOM-required daily production with 455 tankers,” an Air Force spokesperson added.

Now that KC-46 is approved for most joint force receiver-types, the “extra legacy tankers” are not needed, the spokesperson said.

“Inevitably, a Pacific fight would present an uncharted challenge, but we are accepting a measured amount of risk now in order to modernize and prepare the force to compete in a peer fight,” the spokesperson added.

AMC spokesperson Major Hope R. Cronin said that while the KC-46 is still not clear for combat operations, it is used on fifth-generation aircraft with no restrictions. “We can and do refuel all variants of the F-35 and the F-22 with the KC-46 regularly,” she said. “It is taskable by TRANSCOM for missions and it gets tasked for missions.”

Operational KC-46 Closes AMC Refueling Gap

In a quiet backroom at Scott Air Force Base, Ill., on Oct. 5, 2021, then-Lt. Gen. Mike Minihan spoke with Air Force Chief Gen. Charles Q. Brown Jr. Both had served extensively in the Pacific theater, Brown reaching the position of PACAF commander before his appointment as Air Force Chief of Staff, and Minihan with two tours in Korea, two tours at U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, and one in a PACAF staff job.

Brown knew the Air Force needed to quickly overcome challenges in the Pacific. He had urged implementation of the ACE concept as PACAF commander, and he was attuned to the challenges of Pacific refueling. His decision to pin a fourth star on Minihan that day and hand him authority of Air Mobility Command had everything to do with getting after the challenges of the Pacific.

“Five minutes before General Brown promoted me, in the quiet room before we walked down to the ceremony, he told me, ‘Go faster,’” Minihan recalled in a July phone interview with Air Force Magazine.

“The only reason I got this job is because of my time in the Pacific. My experience with the China problem set, my experience with the North Korea problem set, is what afforded me this opportunity. I have a full appreciation of the distances, too, but I also have quite a bit of experience in different headquarters from different perspectives.”

In his first 10 months at the helm of AMC, Minihan has gone after capability gaps in the Pacific theater: command and control, navigation, maneuvering in route under fire, and tempo. All are meant to better equip tankers to support the Air Force in a China fight.

Minihan cannot speed up the tanker recapitalization program, but he does have control of three areas:

- Modifying tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs);

- Taking on more risk; and

- Seeking value that already exists.

Some of the potential solutions he has suggested have already drawn heavy criticism. A new concept called “pilot plus one” would operationally test a KC-46 with a single pilot and a single boom operator while another pilot and boom operator remain in the tanker’s bunk on crew rest. A firestorm erupted over social media when the idea leaked out as Airmen worried it was dangerous to have just one pilot in the cockpit. Minihan said ideas like pilot plus one are part of the “intellectual investment” necessary to weigh the viable options for a crisis scenario. Consider, he suggested, this wartime scenario for a tanker landing under fire at Andersen: “Imagine if they get to Guam, and the airfield comes under attack, and it’s just the first pilot to the airplane needs to get it airborne,” he posed. Testing the pilot plus one concept now could help AMC work out details for how to train for such scenarios.

“My staff, my team, my wings are going to do the proper staffing, understand the risk, understand the benefits, understand the authorities required, and I am going to at least have a risk-informed decision on whether I can achieve that in combat,” he said.

Another concept under evaluation is whether hundreds of C-130E and H models could be resurrected from the boneyard and outfitted as refuelers if conflict required, and to examine what it would take to scale up aerial refueling capacity that way. A well-known idea that Minihan has employed that involved taking on more risk were the seven interim capability releases that approved the KC-46 for 97 percent of taskings, falling short of refueling authority for just the A-10, B-2, CV/MV-22, and the E-4B.

Minihan also began testing the KC-46 in the two theaters where America faces peer adversary threats: Europe and the Pacific.

“Part of my ‘Go faster’ order was to get that girl on step, and the Ukraine-Russia situation offered me an opportunity to get it into Spain,” he said of the KC-46.

While the Russia-Ukraine war is not considered a combat operation for the United States, NATO has dramatically increased its air policing missions on the eastern flank of the alliance. In support of enhanced Air Policing operations along the NATO border, the U.S. Air Force has maintained rotations of combat aircraft, including with fifth-generation fighters operating in the Baltic States, Poland, the Black Sea region, and from a hub at Spangdahlem Air Base, Germany.

Minihan wanted to not only provide refuelers to meet the capacity need, he wanted to prove that the KC-46 was ready. Shortly after the Russia-Ukraine conflict began Feb. 24, Minihan directed 220 Airmen and four KC-46s to Moron Air Base, Spain, to support the Air Policing mission and practice refueling on Spanish EF-18 Hornets.

Throughout March and April, Airmen from the 22nd, 931st, 157th, and 916th Air Refueling Wings flew more than 500 tanker hours. The KC-46 had a 98 percent effectiveness rate, Minihan said, only missing two missions related to weather and lightning.

Turning East

After Minihan proved the KC-46 can operate with high effectiveness in the European theater, he turned East.

“We took that, and we instantly turned it out to the Pacific,” Minihan said of the employment concept exercise he authorized for the KC-46 in the Pacific in June after the successful run in Europe.

“Being in the geography you’re going to fight in matters,” Minihan said. “You cannot appreciate the distances in the Pacific until you’ve flown the distances in the Pacific. You cannot appreciate how much water is out there until you’ve flown over it for five, 10, 12 hours in a row with no land in sight.”

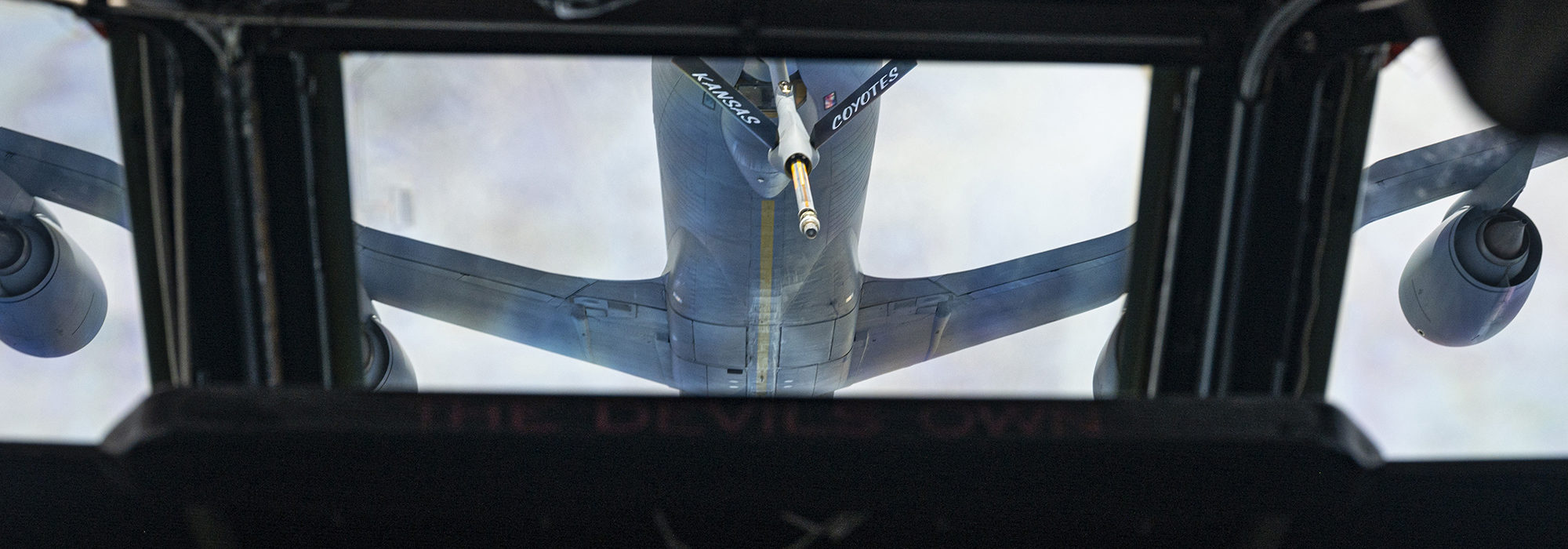

Four KC-46s and Airmen from the 22nd, 931st, and 157th Air Refueling Wings at McConnell Air Force Base, Kan., and Pease Air National Guard Base, N.H., were deployed to Yokota Air Base, Japan, from June 6 to 12 to practice refueling Navy F/A-18 Hornets and Air Force F-35 Lightning aircraft.

AMC points to two distinct advantages the KC-46 has over older tankers in the Pacific: persistence and presence. Since the KC-46 can refuel other takers, it can extend tanker airtime over vast Pacific distances. The tanker provides added presence due to its integration into tactical data links that give it added situational awareness, allowing it to operate in threat-aware and threat-informed locations to refuel combat aircraft closer to the fight.

For the AMC/PACAF staff-to-staff talks, Minihan brought all of his primary directorates for a classified full working day with Wilsbach, followed by a classified session with INDOPACOM Commander Adm. John C. Aquilino and Wilsbach in his role as INDOPACOM air component commander.

Minihan wanted his headquarters staff to get to know their counterparts at PACAF personally. He wanted them to see the slides and the planning documents used for decision-making, and learn the language that the PACAF team in command would use in a Pacific contingency.

“Our alignment with PACAF is seamless,” he said a month after the staff-to-staff. “When I come away from an engagement, especially a direct engagement with General Wilsbach as he puts on his PACAF hat, and he’s incorporating the ACE concepts, and I get that exquisite detail of what the operational commander is going to do in that geography, I come away knowing exactly what I need to do to support that and enable it.”

Wilsbach, too, came away from the staff-to-staff with a better understanding of how AMC can support PACAF.

“We are confident AMC’s capabilities bolsters PACAF’s lethality, ensuring our strategic advantage while allowing our joint forces to seamlessly operate in the region,” he told Air Force Magazine in a July statement.

Upon return from the PACAF and INDPACOM talks, Minihan directed his planners to take the feedback and make adjustments to AMC’s battle plan for the Pacific.

“They are grinding out concepts right now that are going to win with the kit we have, and then we will take that, and we will go back out to those headquarters and resynchronize,” said Minihan.

The AMC commander also directed his staff to take Asia-Pacific Center for Security Studies courses in Hawaii to better understand Pacific geography, countries, political-military, and diplomatic affairs to build a deeper level of understanding about the region. Minihan has urged wing commanders to take every advantage to exercise in the Pacific, and senior planners to incorporate the insights into future exercises. Exercise Mobility Guardian 2023 will consist of several exercises knitted together in the Pacific over several months.

AMC declined to discuss ground fuel storage in the Pacific, directing questions to U.S. Indo-Pacific Command. When it came to the tanker recapitalization plan and Kendall’s objective to draw tanker numbers to an unprecedented 455, Minihan declined to talk specifics.

“Whatever the number I have is the number I’m going to win with,” he said. Minihan said if a crisis were to arise, he would make the KC-46 fully operational for combat operations.

“I would not hesitate one second to employ it for the other 3 percent,” he said of the aircraft not yet authorized for refueling. “We’ve done the work in advance that if we needed to assume the risk for combat operations, I wouldn’t hesitate in a second to put it in.”

Minihan admitted that in a Pacific contingency, the Air Force would not have the aerial refueling assets to maintain all current global refueling operations.

“Priority matters. If everything’s a priority, then nothing’s the priority. So, there has to be a priority established,” he said, naming homeland defense as one mission set that he expects civilian leaders would prioritize if tankers were called off other global missions to support a fight in the Pacific.

“If we’re in a high-end China fight, that is the thing. There’s nothing else going on,” he said. “I got what I need to win. Now, that doesn’t mean it’s going to be a walk-off home run.”