The Air Force’s propulsion program tasked with producing engines for the Next Generation Air Dominance fighter awarded contracts to a mix of both engine-makers and aircraft-builders Aug. 19, hinting that integration could be a priority in the prototyping process.

Boeing, GE Aviation, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and Pratt & Whitney all received indefinite-delivery, indefinite-quantity contracts with a ceiling of $975 million for the prototyping phase of the Next Generation Adaptive Propulsion program.

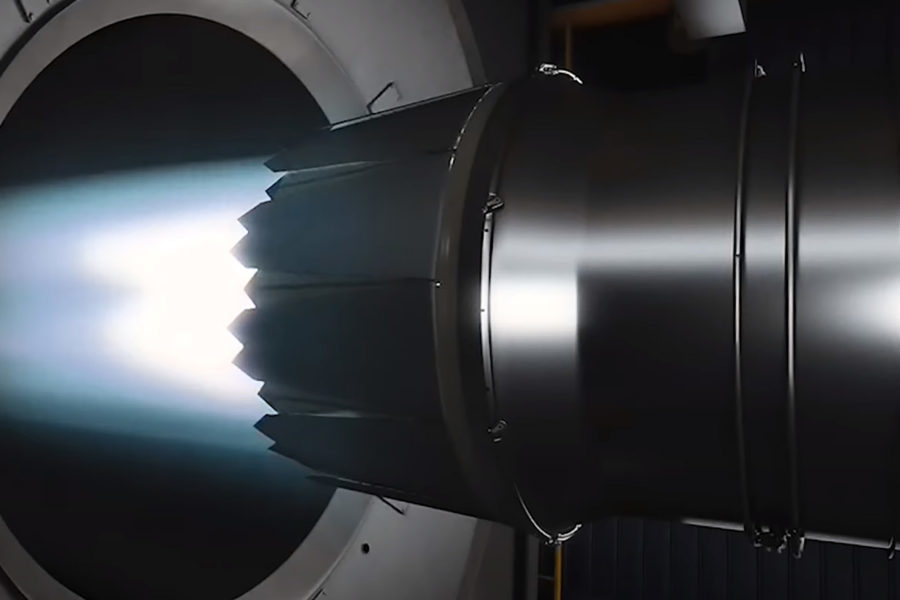

As part of the contracts, those companies will focus on “technology maturation and risk reduction activities through design, analysis, rig testing, prototype engine testing, and weapon system integration,” the award states, with work expected to last until July 2032.

The inclusion of GE and Pratt & Whitney in the NGAP program is hardly surprising. John Sneden, director of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s propulsion directorate, indicated as much earlier in August at the Life Cycle Industry Days conference. The two engine-makers are already competitors in the Air Force’s Adaptive Engine Transition Program.

Boeing, Lockheed Martin, and Northrop Grumman, however, typically don’t make engines. The exact work they’ll be doing as part of NGAP wasn’t specified in the contract award, and none of the three companies immediately responded to inquiries from Air Force Magazine.

But while Sneden has pushed for more competition in the propulsion industrial base—and the contract award states that it is focused in part on “digitally transforming” that base—the three contractors are mostly known for building aircraft, and all three have shown interest in developing a sixth-generation fighter like NGAD.

Their inclusion in NGAP, then, could help steer the prototyping process to ensure that the future engine and fighter integrate seamlessly.

“Any propulsion system has to be built and designed for the specific platform on which it’s operating. And it’s especially true for these adaptive engine systems,” said Mark J. Lewis, executive director of the National Defense Industrial Association’s Emerging Technologies Institute and former chief scientist of the Air Force, in an interview. “So you’d want to develop the engine hand in hand with an airframe. It’s going to be more difficult to make an adaptive engine a sort of a plug-and-play system. Not impossible.”

Lewis was quick to note that his views were speculative. But some of the technological advances coming with the adaptive engines could require fighters built to take full advantage of them, Lewis said. In particular, adaptive engines can transition between modes optimized for thrust and for range.

“Today if you design an airplane, you start deciding, what’s most important. Does it have to have maximum acceleration at this point in its performance? Does it have to be able to fly for a maximum range? And those two requirements, for example, could be at odds with each other,” Lewis said. “With an adaptive engine, you might be able to get the best of both worlds. And so your airframe might reflect that.”

Other considerations, Lewis said, include the third stream of air that is being incorporated into the design of the adaptive engines in AETP. That third stream “changes a little bit the geometry of the engine,” Lewis said.

The development processes of engines and airframes “usually do go hand in hand,” Lewis added, but that can vary substantially depending on the situation. The F135 that powers the F-35, for example, was developed from the F119, which powers the F-22.

But with engines like the ones from AETP and NGAP, industry and Air Force officials have often spoken of a generational jump in capability. And with that jump, Lewis said, it would make sense for the service to ask the companies competing for the NGAD fighter, “If you have an engine that operates along these lines, that can do this differently than previous engines, then what does it mean for the airframe that you’re designing?”

In June, Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall revealed that the NGAD fighter has entered the engineering and manufacturing development phase, but he later clarified that there is still a competition for the program. He did not, however, specify how many contractors are still in the running.