A U.S. government-built app for situational awareness is bringing wildland firefighting into the internet age.

Originating as a product of the Air Force Research Laboratory aimed at improving the precision of close air support, Air Force units have adopted the military’s version of TAK—Tactical Assault Kit—for improving the precision of other activities, such as parachute jumps.

Meanwhile, the free downloads and plugin architecture of TAK’s civilian version—Team Awareness Kit—are giving firefighters, among others, the ability to layer real-time information over satellite images. They can track the locations of team members, vehicles, fires, and a potentially unlimited array of factors to help guide first responders in an emergency.

AFRL still has an office supporting TAK along with a practical reason for wanting more civilian first responders to adopt the app: “Because we want to have everybody on the same page,” said Ralph Kohler, an AFRL principal engineer who promotes TAK to agencies and departments inside and outside the federal government.

Released for Apple iOS earlier in April, the TAK smartphone apps were already running on Android and Microsoft mobile platforms before going live on the Apple App Store.

TAK grew out of the problem of fratricide in close air support, which became apparent in Afghanistan in 2001 when a U.S. service member called in an air strike on his own location—a mistake that occurred after he changed the batteries in his GPS device.

“The number that came up was his position, when he replaced the batteries, not the position he had worked up where he wanted the bomb to be,” Kohler said.

The explosion killed three U.S. troops and five Afghan fighters and injured then-transitional Afghan government leader Hamid Karzai, among dozens of others.

The mistake came down to having “insufficient technology to plot coordinates on a map,” explained Ryan McLean, director of the TAK Product Center at Fort Belvoir, Va.

“So a lot of efforts kicked off out of that,” McLean said. “One of the things that shook out of those problem-solving efforts was through the Air Force Research Laboratory—something called Android Map—which became TAK, which has now become this family of products.”

Akin to one of the Air Force’s software factories, McLean described the TAK Product Center as “a unique organization in the U.S. government” that isn’t funded by any one department but collectively by multiple federal agencies. TAK merged with other apps along the way, and the TAK Product Center has incrementally improved TAK and aspires to achieve “TAK continuous delivery.”

TAK works for fighting wildfires for the same reason it works for close air support, McLean said. Both call for “friendly force identification and target correlation.”

“If you can do those two things, you can do close air support in the military. If you can do those two things, you can also do a lot of other things.

“We can add all these great features—plugins, radios, some pretty novel stuff with geospatial data, open interfaces, open source, all that—but at the end of the day, it’s a capability for friendly force identification and target correlation.”

TAK’s 250,000 users work for local, state, and federal agencies, including 18 DOD and other federal programs of record, with some foreign military sales.

“We’ve all been just absolutely amazed by the combination of friendly force identification/target correlation, with open source [code], with a usable interface. Those three things came together at the right time, and now we’ve seen TAK proliferate and become this massive ecosystem that it is,” McLean said.

The Air Force could find that TAK benefits its part-time Airmen in addition to their Active-duty counterparts. Deputy Secretary of Defense Kathleen H. Hicks said in remarks at the Worldwide Logistics Symposium 2022 that the number of personnel days the National Guard spends firefighting has gone up from just 14,000 to more than 176,000.

Firefighting

Back at the fire station, with good internet, firefighters can call up information on wildfires burning all around the U.S.

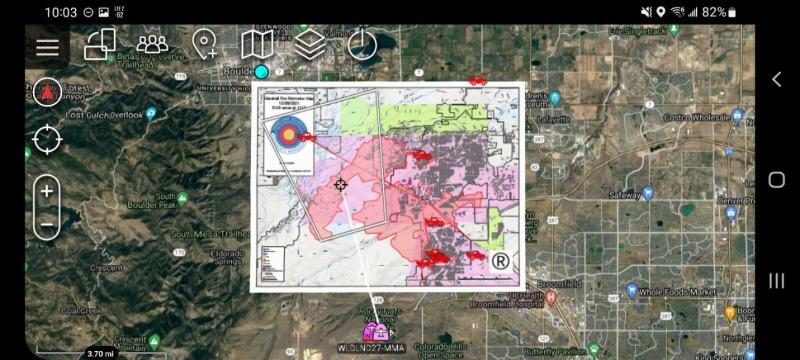

“We can see perimeters. We can see satellite heat detections. We have this wealth of knowledge,” said Brad Schmidt of the Colorado Center of Excellence in Advanced Technology Aerial Firefighting. Schmidt is the center’s wildland fire project manager.

“The part that’s kind of unbelievable in the year 2022 is that when you actually get out onto the fire line … all that intelligence really goes out the window, and we end up relying solely on our walkie-talkie voice radios to communicate with each other and figure out where people are,” Schmidt said.

TAK, on the other hand, can import the shape of a fire, mapped by airplane, and display it along with the positions of the personnel. An example of a plugin add-on, which is in development by Schmidt’s center and the U.S. Forest Service, maps the shape of a smaller fire as a firefighter circles the perimeter, potentially on foot, with a smartphone.

The Corona Fire Department in the city of Corona, in Southern California, borders the Cleveland National Forest. Through mutual aid with the U.S. Forest Service, the local department may be the first to respond to a fire within the U.S. jurisdiction, said Fire Chief Andreas “AJ” Johansson.

“That initial assay of ‘where’s that fire’—that incident commander, that’s what they want to know. ‘How far over the ridge is it?’ If we don’t have an aircraft or a sensor to give us that from a UAS, it’s boots on the ground that will be doing it, so that plugin—we’re getting ready to train our folks on it here pretty soon,” Johansson said. “They are very excited about just the simplicity that Brad has built into this plugin. It really makes it like two clicks to start mapping.”

As a local leader, Johansson appreciates the freedom to freely download TAK, and even to inexpensively add a new feature, without having “to go to a board of a directors for a product that you subscribe to or pay for and say, ‘I need this.’” Because TAK’s code is open source, any department could hire a developer to build a new plugin.

The familiar platforms keep development costs low, said AFRL’s Kohler. “That model has really helped us get a common baseline and get everybody on the same page.”

Getting everyone in sync has included users overseas.

“We’ve integrated with radios in Europe recently to help our European partners, and those integrations are very small efforts,” McLean said. “It doesn’t take a program office budgeting two or three years for that to happen. We can do that very quickly.”

The Future

Colorado’s center for high-tech aerial firefighting envisions a version of TAK to run on augmented reality headsets for aircraft crews who supervise firefighting from above, Schmidt said.

“They kind of have a two-fold job,” he said. “One is to coordinate the whole firefight—get on the radio with dispatch, order resources, talk to the firefighters on the ground, make sure they’re safe, and help them do their job.

“And their other function is to coordinate all the other aircraft that are coming in to actually attack the fire. So all the bigger planes that are dropping fire retardants, all the helicopters that are dropping water, they coordinate that—they do it all—with voice radios.”

Augmented reality goggles, on the other hand, could allow someone “to look out the cockpit with these goggles and see annotated, in their field of view, where people are on the ground,” Schmidt said.

That new degree of awareness—simply on a screen, for now—sums up TAK’s value proposition. As AFRL’s Kohler put it:

“When you know where everybody is, you can figure out what to do.”