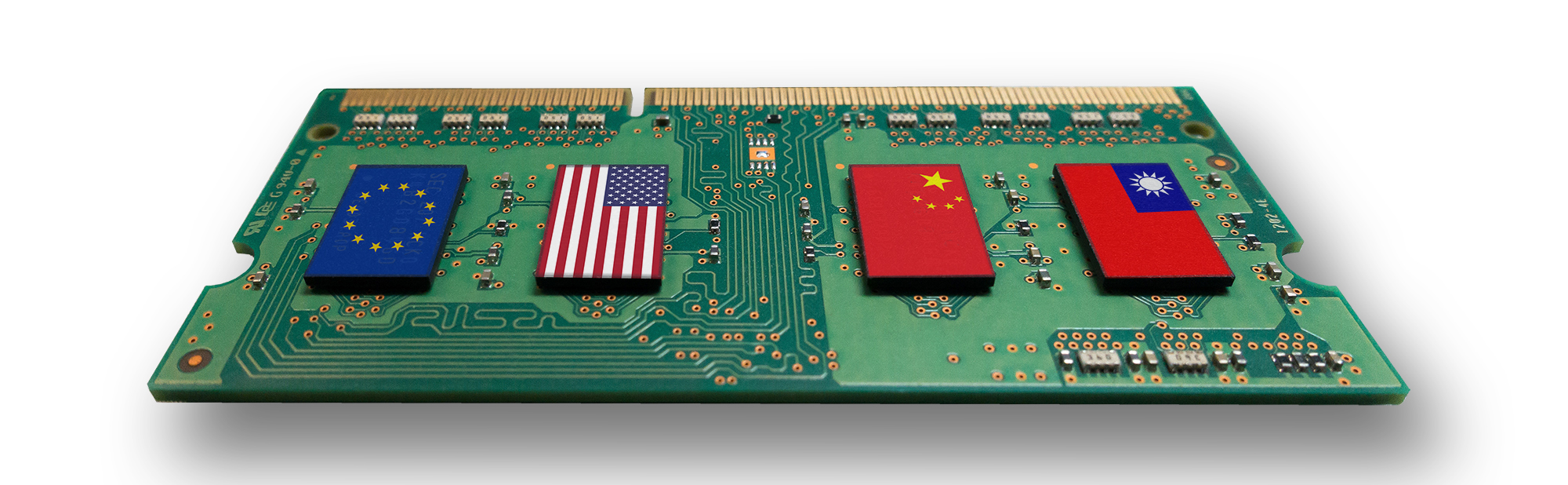

The lack of domestic chip supplies is a growing threat.

It began with the onset of the global pandemic: a global shortage of medical equipment, from masks to gloves, surgical gowns, and hand sanitizer. First there was an oversupply of oil in 2020, driving the futures price to zero. More recently, we’ve seen oil and gas prices soar to levels not seen in several years. Disruptions spread, but the biggest and most far-reaching shortages have been in semiconductors, the computer chips used in everything that requires electronic controls or sensors.

COVID was a driver, including the increased demand for technology to support remote work: There were fires at key Taiwan and Japan manufacturing plants, reduced commercial air flights, which led to capacity problems, and deteriorating trade relationships, including U.S.-China disputes and the U.K.’s messy BREXIT from the European Union.

Apple delayed its iPhone 12; automakers shutdown or slowed factory production; China’s telecom giant, Huawei—already embroiled in a dispute over its government ties and the security of its 5G technology—started stockpiling chips out of fear it would be cut off from the global chip market. And much of the world woke up to overdependence on too few companies and countries for the world’s chip supplies.

Semiconductors are more central than ever to our everyday activities and to the health of the global economy.John Abbott, Analyst, S&P Global Market Intelligence

Chip crises have struck the Pentagon in the past. In the 1970s, the Defense Department launched VHSIC, the billion-dollar Very High-Speed Integrated Circuit Program, to accelerate computer chip development; in the 1980s, it invested a similar amount in Sematech, which included matching industry contributions to try to revitalize domestic chip manufacturing after Japan arose as the world’s leading chip supplier.

“I think we’re going to be still dealing with shortages until we get to some reasonable supply–demand balance through next year,” Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said in an August interview with the Washington Post.

The company says global demand for semiconductors will only accelerate, driving demand for critical third-party components and materials. An Intel spokesperson said they “expect this to last for one to two years.”

Now, Intel is investing $20 billion to expand manufacturing capacity in Arizona and another $3.5 billion to increase production in New Mexico. In addition to manufacturing its own chips, Intel created a new business, Intel Foundry Services, “to provide manufacturing and advanced packaging capacity” for its customers’ chip designs. Building independent capacity in the U.S. and Europe, Gelsinger said, would help “rebalance global supply chains.”

John Abbott, an analyst at S&P Global Market Intelligence, said the cyclical nature of the semiconductor industry lends itself to booms and busts, “with dips in the market having occurred roughly every five years since 1980.” This cycle has seen a double dip, both in 2019 and again now. “Semiconductors are more central than ever to our everyday activities, and to the health of the global economy,” he said. “As a result, supply constraints are holding back production in key market segments like smartphones, game consoles, automotive, healthcare, manufacturing, and defense.”

Major aerospace contractors haven’t faced the extent of shortages that slowed automotive production, at least not yet. But regional breakdowns in the supply chain have highlighted concerns.

Abbott highlights several supply chain danger points:

- Supplier concentration. Taiwan is home to TSMC (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company), the single-largest chip foundry in the world, with roughly half the global market. Another large foundry, United Microelectronics Corp., is also in Taiwan. But Taiwan is at the center of a looming confrontation between China and the West.

- Return to localization. If the pandemic did anything, it exposed the risks of concentrating too much manufacturing capacity in one small part of the world. That’s why Intel is now investing in new U.S. and European capacity and TSMC has announced plans to build additional capacity, including a $12 billion chip fabrication facility (fab) in the U.S.

- Chip-making equipment. This has long been a limiting factor and was a driving element of the Pentagon’s Sematech program in the 1980s. Only one company (ASML in the Netherlands) has the extreme ultraviolet lithography machines needed to produce the most advanced microprocessors, with transistor geometries of 10 nanometers or less. A handful of other, mostly American companies, make machines for larger geometries, and the U.S. government has restricted their sale to China or to companies selling chips to China.

- Changing customers. Chip companies have seen their biggest customers evolve over time, with hyperscale cloud providers, such as Amazon and Microsoft, and consumer device makers, such as Apple. Other growing markets are the plethora of connected devices, from smart thermostats to lightbulbs that make up the Internet of Things, and the growing automotive market.

- Market access. Chip fabrication is expensive. It can take up to three years to reach production in a new factory, and pure fab companies, such as TSMC, rely on high volumes to recoup costs. Location, available skills, the surrounding ecosystem, and licensing issues all play a role in locating a facility.

- Just-in-time manufacturing. Lean inventory practices, which took off in the 1980s as a means of cost control in major manufacturing, took a hit during the pandemic; late shipments idled factories, while canceled orders scrambled supply chains. Manufacturers and suppliers have yet to adapt.

Abbott believes “the shift toward worldwide globalization has been put on hold for now, and may not return,” but technology development is too complex to be controlled by individual countries. The Pfizer vaccine makes a useful case in point, Abbott said: “It has 280 different components manufactured in 86 different sites across 19 different countries.”

Retired Army Maj. Gen. John G. Ferrari, now a non-resident senior fellow with the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., said a commercial shortage inevitably spills over to affect the military.

“The chip shortage is absolutely causing issues within the military supply chain,” he said. “These chips are in everything the military buys and, more importantly, they are embedded in the supply chain, also. In the very near term, military procurement cycles are slow, so we are not likely to see an impact immediately. But the impact will be felt over the coming months.”

Ferrari said supply chain issues could have a disproportionate impact on startups and other smaller defense suppliers. “As the cost of these chips increase, and the time to get them increases, these nontraditional firms do not have the cash flow to weather the storm,” he noted. “This is a potentially very large negative” with long-term effects.

More broadly, the fact that so many of these parts must be sourced from overseas is itself a matter for concern, he said. “The Defense Production Act and the ability of the [U.S. government] to prioritize chips for the military is very limited,” according to Ferrari. “If there ever was [a] shooting war in the Pacific, our ability to quickly rebuild our arsenal and weapons would be severely impacted because it is likely that our supply chain from the Pacific would be interrupted. So this chip shortage may just be a sneak preview of what we are going to face down the road. It is also giving our adversaries a blueprint on how to hobble us going forward.”

Dana “Keoki” Jackson, senior vice president and general manager at MITRE National Security Sector, said the “pandemic has highlighted U.S. and global risks to supply chains that extend beyond semiconductors, and an all-of-nation response is needed to address both near-term shortages and longer-term challenges.” He recommends investing in domestic and allied nations’ industrial ecosystems and providing incentives for sustained industrial base success, as well as “investing in the technology and workforce for the future.”

Rory Green, TS Lombard’s London-based head of China and Asia Research, said the crux of the supply problem is “an unprecedented demand surge because of the pandemic. The ‘Zoom boom’ led to increased sales of a range of semiconductor-intensive goods, from laptops to gaming consoles,” he said. “The demand surge came after several years of low industry [capital investment] and generally falling sales, meaning supply was unable to match the ramp up in new orders. Industry is responding—but it takes approximately two years and between $10 billion to $25 billion to build a new chip fabrication facility.”

In Green’s view, “this looks like another ‘Sputnik moment’ for Western leaders: The growing importance of semiconductors in all parts of economic life, combined with increased superpower competition, is likely to lead to greater focus on reshoring of production to the U.S. and a gradual reorganization of supply chains to favor national security over production efficiency.”

Daniel L. Dumbacher, executive director of the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, called semiconductors “a vital and threatened part of the secure supply chain.” He said the U.S. government must analyze future semiconductor needs, identify potential supply gaps, and collaboratively work with industry to address needs.

One of the most astute analysts of this matter is Matt Bryson, senior vice president of Equity Research/Hardware at Wedbush Securities. He’s examined three elements of the current semiconductor crisis. Here are some of his conclusions:

- Minimal Capacity Growth. Foundry profitability, particularly for mature process capacity, has always been limited. With older foundries struggling to make money in recent years, they’ve underinvested in order to keep costs in check.”

- Strong Demand from New Technologies. Bryson thinks that “the adoption of 5G has driven up semiconductor content within handsets and telecom infrastructure, with adoption of the new technology … occurred faster than expected.” Other new technologies (including electric and intelligent autos, plus the Internet of Things) also require incremental semiconductor content, though the uptick in demand is a bit more modest.

- Poor Supply Chain Management. The impact of shortages “is being exacerbated by order cuts at the start of COVID (due to demand uncertainty) as well as ‘just-in-time’ practices. This approach left companies with limited buffers when semiconductor availability became constrained.

Bryson thinks that the impact of these issues has, in turn, been amplified by the impact of COVID and two additional challenges—logistical (including port congestion and worker shortages) and manufacturing (due to factory limitations in Southeast Asia). These make some of the incremental work more difficult, such as packaging and productizing semiconductors, for instance.

Bryson doesn’t think the semiconductor shortage is tied to locality of supply: “However, the extent of the impact combined with concerns around China’s geopolitical ambitions and tensions in its relationship with the West has certainly led to increased focus on improving domestic supply. Increased focus of governments on where semiconductors are produced, and resulting subsidies to encourage domestic production, will lead to a shift in where semiconductor fabs (and semiconductors) are built.”

Bryson predicts that “new capacity begins to come on around mid-2022, with output from new fabs really starting to kick in during 2023. So, my best guess is sometime second half of 2022/early 2023 is when chip scarcity subsides, though the exact timing will depend upon the product as well as general macro-trends—stronger worldwide economic trends naturally lift semiconductor demand, and vice versa”.

While analysts have some deep insights, no one is better situated than manufacturing executives to understand the dynamics beneath the surface of this crisis. Ganesh Moorthy, Microchip Technology’s CEO, says that the current supply/demand imbalance in the semiconductor industry, “is the worst I have seen in 40 years. In fact, I think the imbalance we have seen between supply and demand has never been this acute in all my history in the industry and it has continued to get worse over the last six months. The rate at which new orders are coming in is outpacing the capacity that we can bring on board. So clearly it is a constraint we are going to see through this year, most likely into next year.”

Moorthy considers this time to be different than previous crises. “This has been brewing for some time. It starts all of the way back in late 2018 and early 2019 when the tariffs started to create headwinds for many of our customers. They could not absorb the tariffs and their end-consumers could not bear the prices, so our demand went down in 2019. As things began to improve, and supply chains realigned so that products destined for the U.S. could be built outside of China, the U.S. was hit by Covid through the first half of 2020. This added to pressure on the demand side, especially in the automotive, industrial and consumer sectors. They all stopped buying,” he pointed out.

Moorthy has been thinking about the steps that need to be taken to ensure this never happens again: “On an ongoing basis, there will be supply and demand imbalances resulting from normal economic cycles. But there are also policy initiatives in the medium to long term that will be important to support a stronger U.S. semiconductor manufacturing infrastructure. Semiconductors are the foundation for our digital economy, and much of what we do depends on them. For both economic and national security reasons, it behooves the U.S. government to ensure the long-term strength and resilience of the American domestic semiconductor industry. This includes both R&D and manufacturing capability, which can be done through policy initiatives. This can be accomplished on the R&D side in the next one to two years. But the biggest issue is the manufacturing side, which will likely take at least three years to address—from when government initiatives are launched to when we see results at the industry level.”

Semiconductor supply can be manufactured domestically for the aerospace and defense sector. This is increasingly seen as vital, due to concerns around hacking, counterfeit parts, and other issues. Moorthy is optimistic about these prospects: “We already build a fair amount in the U.S. for the defense part of our business. We have other proposals that we have made that can allow us to do more for the defense industry, we do have manufacturing in-house and most of it within the U.S. as well. There is the opportunity to do more but it has taken a long time to get where we are.”

Gordon Feller serves as a Global Fellow at The Smithsonian Institution’s Wilson Center.