The COVID-19 disease isn’t a biological weapon and probably wasn’t genetically engineered, and Chinese officials likely didn’t know about it before the first outbreak in Wuhan, China, in November 2019, according to a new report from Avril Haines, U.S. director of national intelligence.

But the Intelligence Community has reached no consensus on the specific origin of COVID-19, assessing that it could have started with an infected animal or a lab mishap, and the agencies say China isn’t being helpful in nailing down a definitive answer.

The findings are part of an “updated assessment” of COVID-19’s origins that Haines’ office released Nov. 2.

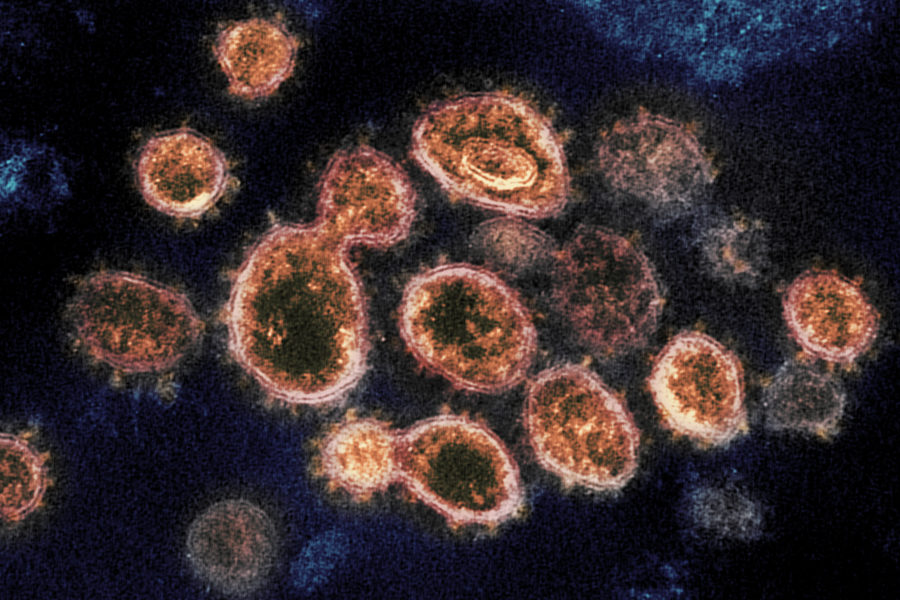

The virus that causes COVID-19—SARS-CoV-2—lacks “genetic signatures … that would be diagnostic of genetic engineering,” the report said, and no existing coronavirus strain has been found that “could have plausibly served as a backbone” if it had been engineered. Moreover SARS-CoV-2 naturally recombines and mutates, suggesting that the pandemic variant isn’t artificially contrived. Nevertheless, analysts don’t have higher confidence that it’s not an artificial strain because “some genetic engineering techniques can make modifications difficult to identify, and we have gaps in our knowledge of naturally-occurring coronaviruses.”

The IC “remains divided on the most likely origin” of the pandemic, according to the report, narrowing it down to “natural exposure”—most likely in one of China’s “wet markets,” which deal in bush meat and unconventional foods—and “a laboratory-associated accident.”

The IC can’t provide a “definitive explanation” for the origin of COVID-19 without more information, it said. Specifically, it lacks “clinical samples or a complete understanding of epidemiological data from the earliest COVID-19 cases.”

More information could produce a conclusive answer, but China “continues to hinder the global investigation,” resists sharing information, “and [blames] other countries, including the United States,” the report said. The IC says these behaviors indicate the Chinese government’s uncertainty “about where an investigation could lead” and its frustration that “the international community is using the issue to exert political pressure on China.”

There are “numerous information gaps, particularly related to technical data,” from China, the report said. China will have to offer “greater transparency and collaboration” in order to “close information gaps on the origins of COVID-19.” The IC called on Beijing to reveal more about its coronavirus research that might confirm “a laboratory-associated incident or at least some new insights.”

The IC also noted that China has been uncooperative in allowing World Health Organization investigators access to research sites and claimed that WHO investigations were “politicized” and that Beijing would not cooperate with future site visits because it alleged the WHO was engaging in “conspiracy theory,” according to the report.

China is also “pushing its narrative that the virus originated outside China,” suggesting it came from imported frozen food, which the IC called “an extremely unlikely theory.” China has also charged—”to divert attention away from Beijing,” according to the report—that the U.S. intentionally spread SARS-CoV-2.

The IC said it believes the “first cluster” of cases arose in Wuhan in late 2019, “but we lack insight—and may never have it—on where the first SARS-CoV-2 infection occurred.” In its one nod to China’s theory, the IC said, “it is plausible that a traveler came in contact with the virus elsewhere and then went to Wuhan,” but so far, there’s no “credible evidence” of an outbreak anywhere prior to the first reported cases in late 2019.

Twelve coronaviruses from 77 percent to 96 percent similar to SARS-CoV-2 have been identified since 2013; one each in Cambodia, Japan, and Thailand, and the rest in China. Ten came from bats, and two came from pangolins. Of the 12, all are at least 77 percent similar to COVID-19, with four being more than 94 percent similar. Even so, “an immediate precursor virus strain and animal reservoir have not been identified.”

The natural exposure hypothesis, to which four segments of the IC subscribe “with low confidence,” is supported by China’s “lack of foreknowledge, the numerous vectors for natural exposure, and other factors,” Haines’ report said. China’s wet markets sell “live mammals and dozens of species—including raccoon dogs, masked palm civets, and a variety of other mammals, birds, and reptiles—often in poor conditions where viruses can jump among species, facilitating … novel mutations.” Hubei province, where COVID-19 seems to have started, “has extensive farming and breeding of animals that are susceptible” to SARS-like illnesses, “including minks and raccoon dogs.” China’s regulation of wet markets is “lax,” and conditions in them “increase the probability” that transmission occurred this way.

One segment of the IC assesses with “moderate confidence” that a Chinese scientist caught the disease while working with SARS-CoV-2 or a close progenitor. The exposure could have come from contact with a lab animal or leakage, and the proponents of this answer “give weight to the inherently risky nature of work on coronaviruses.”

Three other IC segments were “unable to coalesce” around a single explanation without more information.

“Variations in analytic views largely stem from differences in how agencies weigh intelligence reporting and scientific publications and intelligence and scientific gaps,” the report said.

The report said the IC conducted a 90-day study of the issue, during which the DNI encouraged them to “emphasize points of agreement” and “solidify consensus.”