Global Engagement is Necessary to Strengthen America’s Space Network, Space Force Leaders Say

America’s space-dependent way of life and its military space advantage are threatened by the new space weapons wielded by adversaries. But in just two years, Space Force is motivating traditional and new partners to fill strategic gaps and to guarantee access to space through investment and information-sharing, as long as the right barriers can be broken down.

One month on from a chiefs meeting in Colorado Springs that brought together heads of space agencies from 22 nations, U.S. Space Command and Space Force were marching ahead with the global engagement necessary to strengthen America’s space network and create a globally dispersed partnership.

U.S. Space Force Chief of Space Operations Gen. John W. “Jay” Raymond highlighted the growing partnership at the Air Force Association’s Air, Space & Cyber Conference in National Harbor, Md.

“We had representatives from every continent except Antarctica,” he said, noting how the international chiefs conference doubled its attendance from its first iteration two years prior.

“It is clear that we are stronger together,” he added. “We operate together, we train together, we now are developing capabilities together. And for all the international partners that are here, thank you for being here. Again, we are stronger together. And we look forward to continuing to build that team.”

The Colorado meeting focused heavily on the need for greater space domain awareness and norms of behavior in space to counter the types of threatening anti-satellite capabilities that adversaries such as China and Russia have demonstrated on orbit and from the ground.

Commander of Space Operations Command Lt. Gen. Stephen N. Whiting said America’s military edge can be made more resilient through its partners.

“Space brings us untold advantages, such as being able to overfly other countries legally,” he said. “You can’t fly in airspace above other countries because that’s sovereign territory, but that also means that you are regularly and predictably over other people’s countries in what we call their weapon engagement zone.”

From a defense standpoint, that means while America is developing a more resilient space architecture, it must defend the current architecture until hardened capabilities can be deployed.

“We are looking at all the kinds of capabilities you expect in a military organization: intelligence, cyber, command and control, force packaging, high-value capability, defense, offense, multi-domain,” Whiting said. “How do we bring all of that together to protect our assets?”

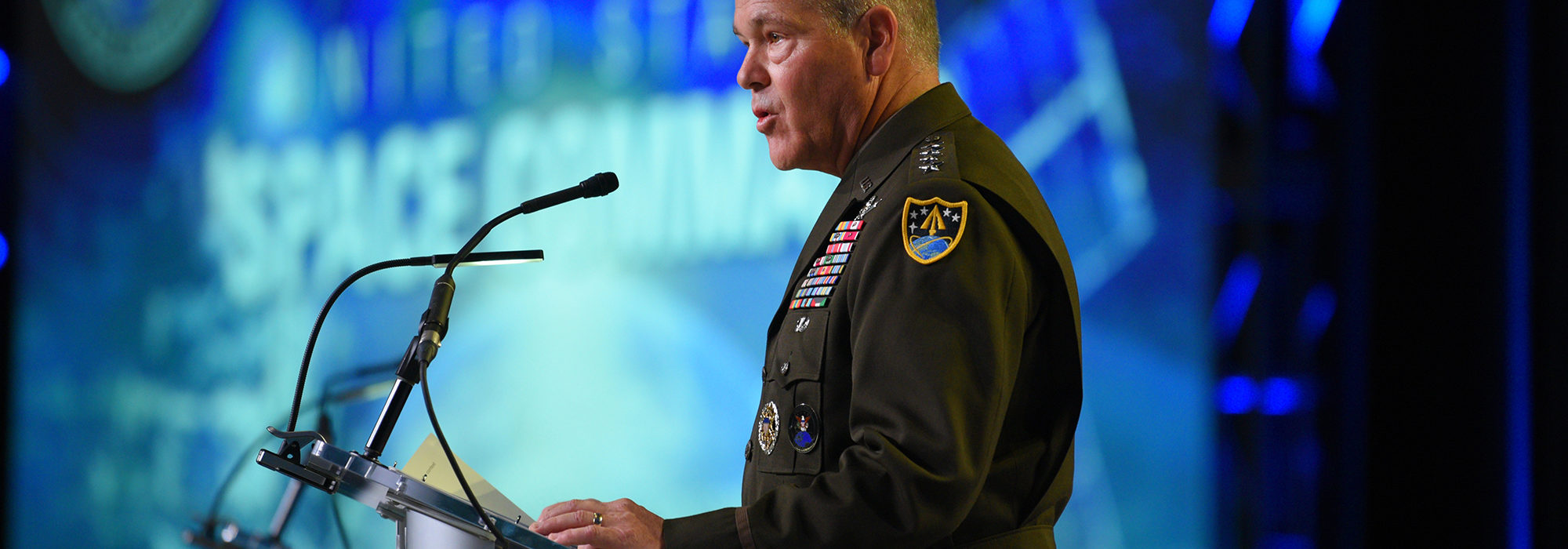

Supreme Allied Commander Europe and head of U.S. European Command Gen. Tod D. Wolters said space’s importance must not be underestimated.

“Once you get a taste of what space can do for you, it’s very, very infectious,” he said. “We should lead from the front in how we embrace space, how we embrace cyber, how it’s baked into our activities to generate peace,” Wolters said. “We should continue to take time as uniformed military members to adequately communicate to senior civilian leadership what it is we are doing in these two domains to generate peace.”

While America’s military leaders are protecting space assets and developing new, hardened capabilities, the Space Force is working on its own to strengthen international space partnerships and fill gaps in capability.

Finding Common Ground in Space

Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. David D. Thompson said partners are approaching the United States and asking how they can best add to allied capability. He cited Australia as one example of a partner seeking to strengthen its partnership with the U.S., as well as Japan, which has been eager to host American payloads and improve data-sharing.

Thompson also cited European partners, including France and Germany, which stood up its own space command in July.

The U.S. SPACECOM commander, Army Gen. James H. Dickinson, has been hopscotching the globe to strengthen partnerships, according to USSPACECOM’s deputy director of strategy, plans, and policy Brig. Gen. Devin R. Pepper. Dickinson visited France, South Korea, and Japan in recent months, Pepper said.

“We have what’s called an integrated priority list,” Pepper said. “That IPL [pronounced “ipple”], as we call it, lists the priorities, the things that we are most concerned about, and really the capability gaps that we have as a nation.”

The list informs allies “exactly where they can spend that next dollar.”

“The IPL helps them understand where we are asking for assistance when we need their help to close some of those gaps,” he said.

Maj. Gen. Hiroyuki Sugai, Japanese air and defense attaché at the Japanese Embassy in Washington, D.C., watched Raymond’s presentation live.

“Space is very competitive,” he said. “Some countries like … China and Russia or North Korea launch missiles or satellites that might jam our satellites. That is a big threat.”

To protect itself, Japan is investing in space, building closer ties to its allies, and analyzing how to defend its satellites from the jamming threat. Japan plans to stand up a space situational awareness system in 2023 using deep space radar, establishing what Sugai called the nation’s “first space capability.”

“For every program, we need to align with Space Force, because we don’t have the capability for space,” he said. “Its just beginning. We have a close cohesion with Space Force for how to build up our capability.”

Japan wants to make sure its space data-tracking systems integrate with Space Force systems in real time.

Today, Japan’s space operators are limited to a squadron of about 20—but more will be added over time.

Similarly, Germany is sending an important signal by standing up its new Space Command, German Air Force Col. Marco Manderfeld told Air Force Magazine.

“Its an outside signal to our partners that we take space seriously and that we take the collaboration seriously,” he said during the Space Foundation’s August Space Symposium in Colorado. The objective is “to send a strong signal of how we view space and [that] we want to be part of an international community.”

Manderfeld said establishing the U.S. Space Force two years ago was an important political motivator for allied political and military leaders in Germany.

“To stand up space is also a question of resources and prioritization,” he said. “If you want to get resources, you have to make a strong case, and pointing out what efforts our allies undertake to make space real definitely helps in the development of our space capabilities.”

While Germany’s Luftwaffe does not have a designated space career field yet, there are space specialists who work closely with allies.

“Just look at the starlit sky—to use a picture—and how can you not see how big this problem is?” Manderfeld said. “It’s actually too big to tackle it alone, even for the U.S. with the Space Force resources.”

Germany has long seen space as ripe for collaboration in information-sharing from sensors as well as analysis.

“There are gaps, and all the allies bring surge capabilities to the table that fill out these gaps,” he said. “Just verifying results that one of the allies brings to the table, and then discussing it and [getting] a picture and more resilient idea of what’s happening up there.”

The geographic dispersion of allied capabilities is also valuable, said British Group Capt. Peter Warmerdam, assistant air and space attaché for the United Kingdom in Washington, D.C.

“We offer the U.S. a number of interesting locations across the globe,” Warmerdam said.

“We built our own U.K. Space Command. We are looking to integrate on a daily basis more and more,” he said, describing his nation’s extensive exchange program and liaisons at Space Command.

Space is “the metaphorical high ground,” Warmerdam added. “Space is intrinsically important to day-to-day life, and we recognize that there are people out there that perhaps don’t necessarily work to what we would see as acceptable behaviors in space.”

U.S. Space Command’s Pepper said establishing closer ties with partners means greater information-sharing and transparency among allies and partners in space.

“The first thing we have to do is, we’ve got to break down the security barriers,” he said. “We can’t talk to our allies without making sure that space is at a classification level that we can share with our allies.”

Pepper said easing today’s overclassification is critical to helping the Space Force articulate its challenges, communicate its capabilities, and cooperate with allies.

“We have to do this early,” Pepper said. “We can’t wait until 11 p.m., right before the fight starts, to figure out how we’re going to fight together. That’s too late. …. Being able to communicate and share information, share data, integrate our allies into the fight, is the most important thing that we’re focusing on right now.”