COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo.—Space Force acquisition leaders were already looking to see if they could shift some of their biggest programs to use commercial services or technology, but one of President Donald Trump’s executive orders, signed April 9, that could super-charge that effort.

Now, the service’s vision for going beyond conventional Pentagon-industry partnerships has an even greater sense of urgency, those leaders said at the Space Symposium.

“It’s a change in our culture, and it’s a change in our thinking,” Lt. Gen. Philip A. Garrant, head of Space Systems Command, said of the emphasis on commercial space capabilities. “It goes all the way back to the programming piece as we develop the budgets, because if we don’t pre-plan it, by the time it gets into their strategy, it’s too late. The PEOs need to make sure strategy is included as a forethought, not as an afterthought. That’s when the real power is going to happen. And [as] you’re seeing, we’re finally putting our money where the mouth is.”

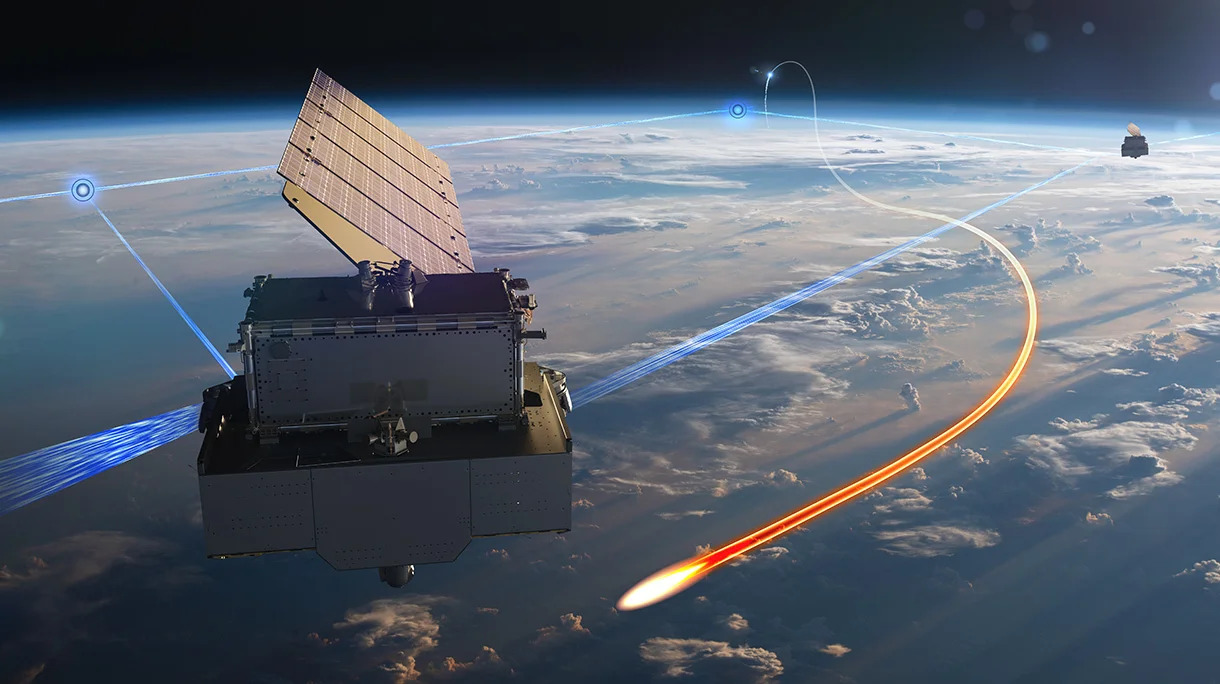

The Space Force’s embrace of commercial has been a long time coming. A year ago, leaders unveiled their first Commercial Space Strategy after months of work, pledging to build “hybrid architectures” of government, allied, and commercial satellites and systems across a wide range of missions.

By the end of the 2024, Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. Michael A. Guetlein and then-service acquisition executive Frank Calvelli issued guidance to program executive officers, said Col. Rich Kniseley, head of the Commercial Space Office: “Look over their mission area requirements and … see which ones of those can we now move over to commercial, international, and what has to be purpose-built,” Kniseley said.

Calvelli left his seat at the change in administrations, but his military deputy, Maj. Gen. Stephen Purdy, took things a step further in early 2025, when he assumed the role of acting SAE.

“Every major program at SSC, all the traditional programs, have taken an excursion. They’re not stopping the program of record, but they’ve taken a side excursion,” Garrant said. “And the ask was, ‘if I, Gen. Purdy, were to cancel your program, how would you meet your requirements purely commercial?’

“So in my mind, it’s a fantastic exercise. It nests right with the commercial strategy. It’s aligned with the pivot we’re trying to make. And everything’s on the table. … Nobody got a pass. Everybody has to do this excursion of, ‘Could I start over and meet my requirements commercially?’” The results of those drills aren’t in yet, but “this wasn’t just an academic exercise.”

Trump’s executive order, aimed at modernizing and reforming the notoriously slow Pentagon acquisition process, serves as an “exclamation point” to the message Space Force leaders had been sending, Kniseley said. It calls for the Pentagon to develop a plan for speeding up acquisition, to include a “first preference for commercial solutions.”

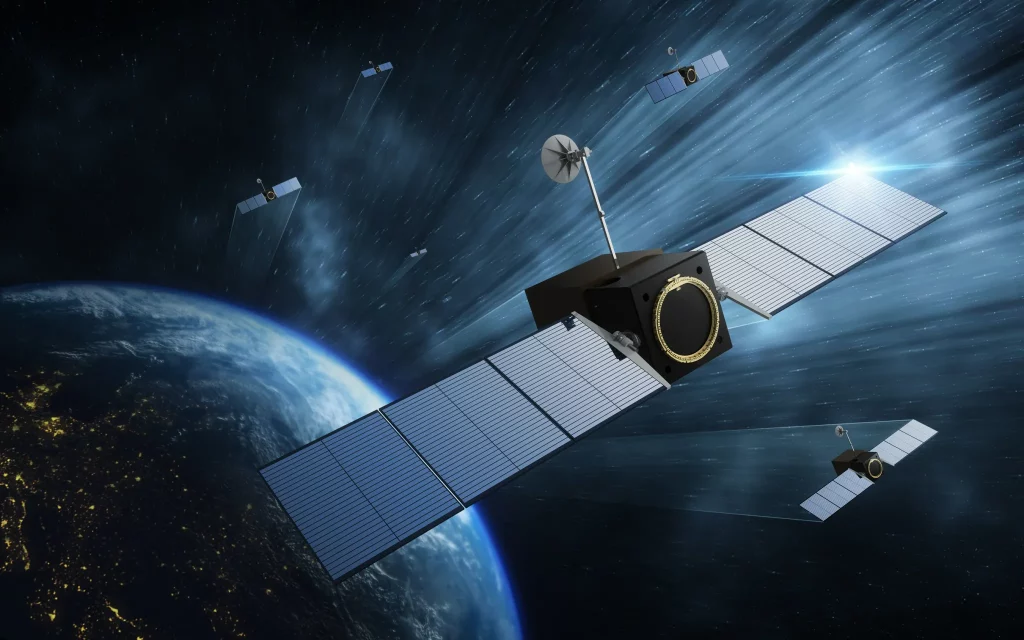

In some areas, the Space Force and its predecessor organizations have already shown they can do it. Todd Gossett, an executive with satellite communications provider SES Space & Defense, said during a panel discussion that SATCOM companies have “seen, over the past decade, a much more purposeful integration of these commercial capabilities into the military alongside military purpose-built capabilities and what we now call hybrid space architecture.”

In a roundtable with reporters, Charlotte Gerhart, deputy director of military communications and position, navigation, and timing at SSC, confirmed that approach, saying she and her team are “continuously looking [at] ‘what can we pull in? How can we be faster and less expensive and more capable by pulling in the newest, latest technology commercial uses?’”

Still, the U.S. military space enterprise is known for taking decades and spending billions of dollars to procure its own exquisite, custom systems. Simply the possibility of canceling contracts that are years along, worth hundreds of millions of dollars, is a major shift.

A “frozen middle” of procurement officers who resist a more flexible, commercial-friendly approach doesn’t help, Gossett said.

Kniseley, himself a career acquisition officer, agreed, saying program managers are inclined to focus on cost, schedule, and performance without considering commercial alternatives.

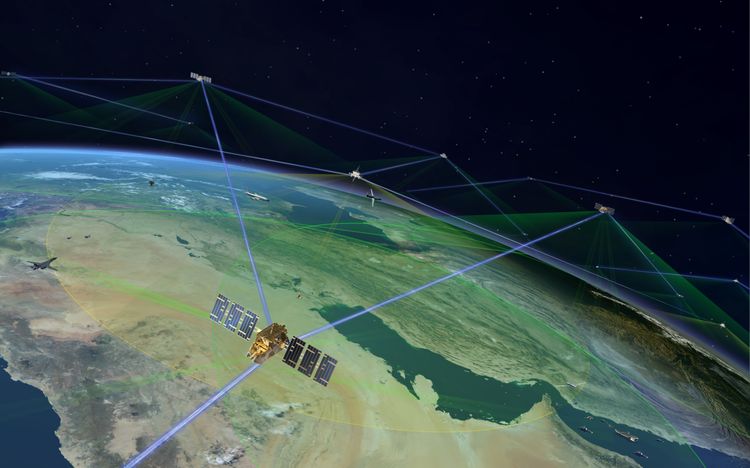

Those alternatives may not fulfill every requirement in a program, Kniseley noted, but they can speed help to warfighters in the field. That alone makes them valuable as the U.S. races to keep pace with its adversaries, said Air Force Col. Eddie Ferguson, chief of advanced warfighter capabilities and resources analysis division at U.S. Space Command.

“We have a 2027 timeframe that [SPACECOM Commander Gen. Stephen N. Whiting] gave us,” he said. That demands using commercial partnerships, “preferably with dual-use technologies, because that’s what’s going to deliver in the timeframe that we’re looking at.”

There are other hurdles besides procurement officer inertia, though.

Commercial leaders frequently tout the innovation of American industry, but need to show they can meet the stressing demands of the military, which often go beyond what’s required for a commercial product.

“The challenge is, can you develop enough trust? Because most of us are coming from Silicon Valley,” or other non-traditional backgrounds,” said Joe Morrison, general manager of remote sensing at Umbra, a sensing and imaging firm. “There’s been a lot of big promises, [but] a lot of under-delivery. Can you trust us enough to share with us what your actual needs are?”

Once the government does that, industry still needs to fulfill its own, commercial purposes.

“It is a fundamental tension in the relationship where we are developing something that we think is the best way to solve a problem, and may be different than what a government customer has asked for or has envisioned for that need,” said Michael Madrid, chief growth officer at Starfish Space, a satellite servicing company.

The military, on the other hand, can’t afford to rely on a company that might go out of business or want to pull out of an agreement when the fighting starts and their satellites are being attacked.

“As we start to work with new … companies, we evaluate their financial viability, long term, Garrant said. But they are then “part of our Department of Defense architecture. You’re now at risk. You’re a legitimate target, right? What are the implications there?”

A clear and consistent message conveyed when dealing with companies is that those “providing services or capabilities to the United States military understand the risk,” added Ferguson.

Nevertheless, the industry and military space officials agreed that the ties between them are set to grow.

“It takes a lot of top-down pressure in order to change culture, while also building up from the bottom,” Kniseley said. “So having an executive order that says ‘go commercial first,’ having the Vice Chief of Space Operations and the SAE look to prioritize commercial, having Congress put it into the NDAA to prioritize commercial … you’ve got all the top-down pressure. But now it’s on the program executive officers to change how they procure things.”