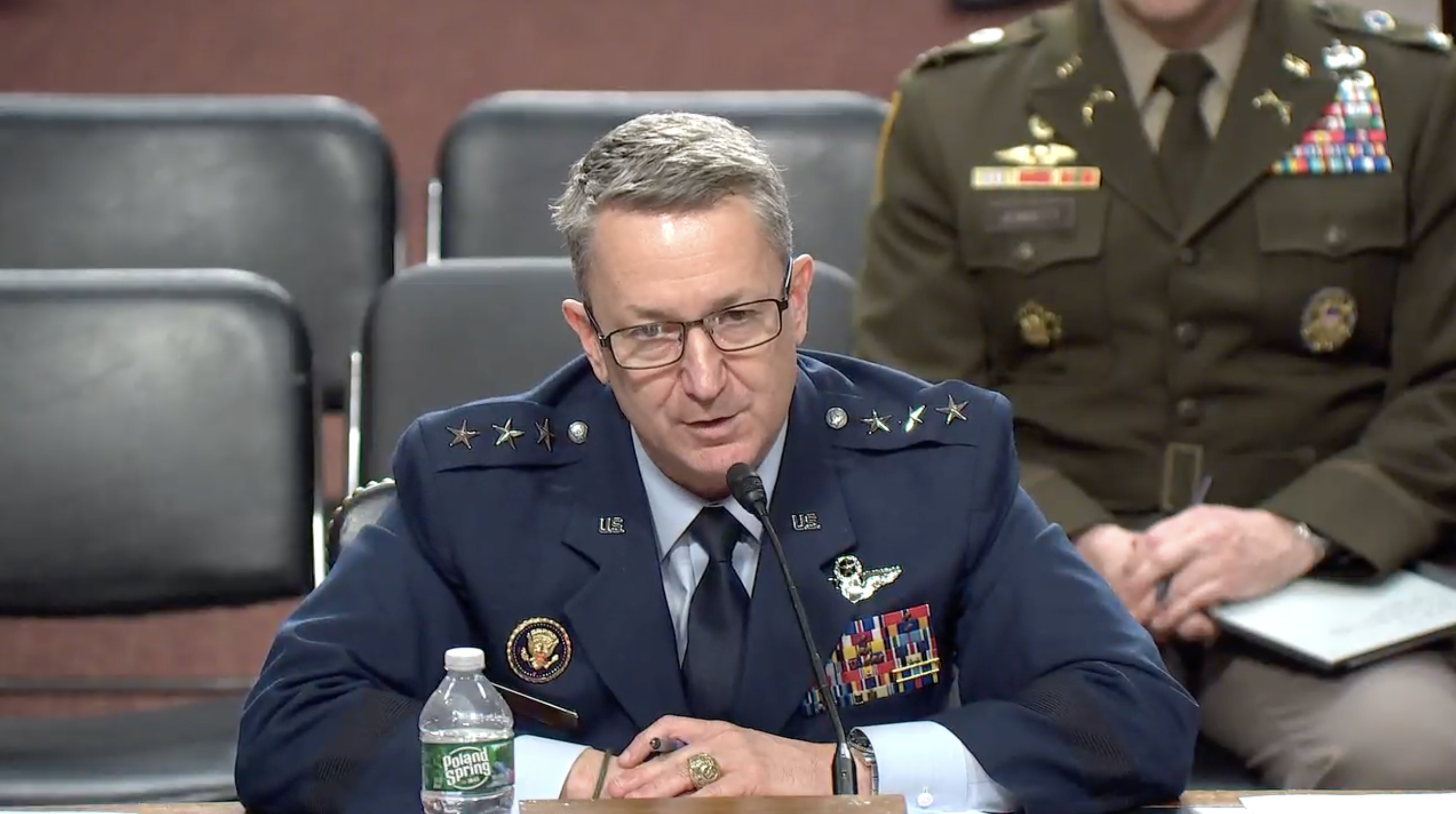

As it develops new weapons to attack satellites, the U.S. Space Force is focused more on ground-based efforts where the technology is more mature, the service’s top general said April 3.

“Our initial energy—and some of this is because of the technology readiness level in our industry—is mostly ground-based, looking up to space,” Gen. B. Chance Saltzman told the bipartisan U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission, an advisory panel chartered by Congress.

“As you start to move to orbit, the technological threshold is a little higher, and so we’ve not put our dollars there initially. And so we are more interested right now in ground-based capabilities,” he added.

China, on the other hand, is “investing heavily” in both ground and space-based weapons, Saltzman warned.

The three kinds of non-cyber weapons—kinetic weapons, directed energy weapons, and radio frequency jammers—“can be on orbit, or can be on the ground, pointed up. The [People’s Republic of China] is investing heavily in all six categories,” he said.

China’s investments in anti-satellite weapons, sometimes called counter-space capabilities, and other technologies like quantum satellites, “represent an inflection point in space access that may result in China overtaking U.S. leadership” in the domain, he warned.

At the same time, China’s progress in space means that it is becoming more dependent on space-based capabilities, and therefore more worried about aggressive kinetic testing, like the Russians’ use of a direct ascent anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon in 2021, Saltzman added. That may reach a point where it causes friction between the two nations.

“The PRC has developed such a need for space capabilities that the idea of irresponsible behavior by anybody else is starting to affect the way they see the space domain as well,” Saltzman said. “It used to be that only the U.S. really took full advantage of space, and others didn’t need it as much, so it became a vulnerability.

“Now I think the PRC, for example, certainly needs to use space capabilities to achieve what they want to accomplish. … They did not like the 2021 destructive ASAT test by the Russians either. This is irresponsible behavior, and I think they see that it could potentially jeopardize the way they want to use space.”

Nonetheless, Saltzman added, there is still potential for the two U.S. adversaries to cooperate. “My job is to think about the worst-case scenario, and that’s where they collude to work against our national interests,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Space Force is fighting with one hand tied behind its back, constrained by policies based on outdated ideas about space, bemoaned Saltzman.

“We continue to struggle with overly restrictive space policy and outdated ways of thinking, dating back to when space was a benign environment,” he said in his written testimony, “Much of our guidance and direction continues to frame space as a strategic resource rather than a warfighting domain.”

Moreover, “We restrain ourselves from doing what is needful to avoid creating improper perceptions of ‘weaponizing space.’ In reality, space has been weaponized for at least two decades, and our slowness to absorb that reality has held back our progress.”

Asked to elaborate during the hearing, he said Space Force commanders “still have to go to very high levels of approval to do some of the basic things that you would think are just normal operations, testing, tactics, development, training.” He added that Guardians often had to train “in simulation, not in actual live practice … because of policies are in place.”

He said he believed that when policy issues get the high-level attention they need, leadership generally comes out with the right answer, but it takes work to get there

“I wouldn’t characterize this as … we chose the wrong policy,” he said. “I characterize it as, to some degree, space has been literally out of sight, out of mind, and so it just hasn’t risen to [a high enough] level.”

Whenever the Space Force tries to get a policy changed “whether it’s testing capabilities or or putting resources to a particular kind of capability, when those rise to the right level, generally, we can get people to acknowledge, yeah, this is probably a good idea. It’s just still a low priority in terms of the policy regime to even take a look at. And so I just feel like we’re lagging in the importance of establishing declaratory policy, and establishing the kind of policies we need to move fast.”

On the other hand he acknowledged that space is seen very differently than it was a decade ago, a change in the national conversation prompted, to some degree, by the Space Force’s establishment.

“I’m not afraid to say offensive capabilities. … I’m not afraid to say disrupt, deny, degrade,” enemy satellites, he said. But he acknowledged that “10 years ago, I would have been in serious trouble with my bosses, with Congress, with the media.”

Asked whether China was pulling ahead of the U.S. in terms of its space capabilities, Saltzman said the picture was more complicated than implied by the analogy of a “space race.”

“A race implies a very simple set of rules that everybody understands, and somebody’s ahead and somebody’s behind, and you cross the finish line and you can determine who the winner is,” he said. “It’s far more nuanced than that. And so to say one person’s ahead or their learning curve is faster, [is] to some degree, overly simplistic, but I understand why the question is asked.”