Images of the F-47 Next-Generation Air Dominance fighter, released by the Air Force on March 21 when the program was awarded to Boeing, are mere placeholders and aren’t intended to accurately portray the aircraft, despite showing only a small portion of it, Air Force and industry officials told Air & Space Forces Magazine. The idea is to keep adversaries guessing about the true nature of the NGAD design.

The images show a stealthy-looking aircraft from its nose and cockpit back to the leading edges of the wings, which display pronounced dihedral, or an upward-angle. They also show canard foreplanes, which appear to be fixed, not articulated. No air intakes are shown.

Although many aviation experts have penned extensive analyses of the F-47 images, particularly of the canards—the use of which would be difficult to square with the notion of the F-47 as an “extremely low observable” design—they should be “taken with a large grain of salt,” an Air Force official said.

“We aren’t giving anything away in those pictures,” he said. “You’ll have to be patient” to see what it really looks like, he said, adding “Is there a resemblance? Maybe.”

A former senior Pentagon official, asked at the time of the F-47 announcement about the unusual canard and wing configuration, replied, “Why would you assume that’s the actual design?”

Sources said that, in anticipation of the NGAD announcement, Boeing artists produced images that already deliberately distorted some of the NGAD’s features, and the Air Force then further altered them. Boeing Defense, Space, and Security does not use any of the released images on its website and did not include them in its NGAD announcement press releases.

An Air Force spokesperson noted that the two images are available on the Defense Visual Information Distribution Service (DVIDS), where they are labeled as “artist renderings.” An Air Force spokesperson said they are “free to use.”

As for the canards, the former defense official said “it’s possible to have canards and be stealthy,” but stopped short of saying that they are indeed a feature of the F-47.

China’s J-20 Mighty Dragon fighter, whose stealth Air Force officials have characterized as being in the same class as that of the F-22, employs a canard and delta wing design, but deflection of those control surfaces have to be managed extremely carefully so as to not to break the angles required to be low-observable to radar.

The Air Force has a long history of withholding imagery of stealth aircraft until the real articles are about to break cover and fly where they can be seen—and photographed—by the public. But even then, the Air Force has consistently shown only distorted pictures in the early days of revealing new stealth aircraft.

B-2

In April 1988, the Air Force released the first official image of the Northrop B-2A stealth bomber; a painting that blurred-over the aircraft’s exhausts and presented the aircraft from an angle that made it difficult to determine its true wing angle of sweep, size, and intake configuration.

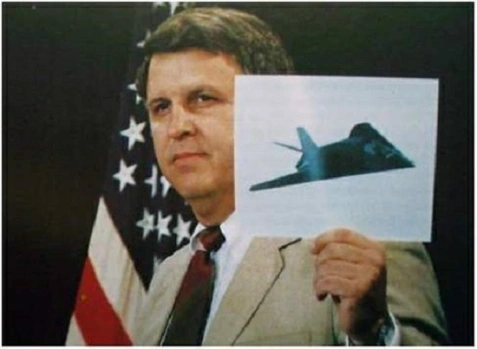

F-117

In November 1988, Pentagon spokesman Dan Howard displayed a heavily doctored photograph of the then-secret Lockheed F-117 stealth strike aircraft at a press briefing. The first image was foreshortened to disguise the true angle of sweep of the F-117’s wings, and create ambiguity about its engine intakes, exhausts, sensor apertures and size. The tactic was so successful that model companies rushed to production with kits that featured broad wings like those later seen on the B-2 bomber, rather than the true narrow, arrowhead shape of the F-117. The Air Force only fully revealed the F-117 in 1990, because the jet, which had previously only flown at night and mainly in restricted airspace, was about to participate in daytime training missions.

F-22

Lockheed used fictional but consistent imagery of a delta-wing fighter with canards in its late 1980s advertising during the Advanced Tactical Fighter competition. Only when the Air Force officially rolled out the YF-22 in 1990 was the true, conventional planform of the fighter revealed.

B-21

The first artist’s rendering of the B-21 Raider, released in 2016, obscured the air intakes and exhausts, and left most of the cockpit transparencies in shadow; again presenting the aircraft from an angle that made it hard to determine its size and wing angle of sweep. Subsequent artist’s concepts were released in 2021 revealing the unusual configuration of the cockpit transparencies, and more detail of the depth of the keel and shape of the wings, but continued to conceal the intakes and exhausts. It was not until the aircraft’s rollout in December 2022 that details of the nose were revealed. At that event, photographers were strictly limited to photographing the aircraft from the front only. And it was not until the first flight from Northrop Grumman’s Palmdale, Calif. facility in November, 2023—not announced ahead of time—that the true shape of the planform and first details of the exhaust were captured by non-government photographers on the airfield fenceline. The Air Force did not release official images of the B-21 in flight until several months later.

The only departure from this pattern involved the Joint Strike Fighter. The companies in that contest were free to share artist’s concepts of their aircraft during the late 1990s, and the nearly-final configuration of the F-35 was displayed at the time Lockheed Martin was selected as the competition winner in 2001. At that time, however, there was less concern about adversaries gaining insight from such imagery: Russia’s military was considered moribund from lack of funds, while China was not yet considered capable of exploiting such information.