Power projection is more than projecting military might—a nation’s economic power is the foundation of its capacity to project national power. And technological development is an important component of that power. In citing its reasoning behind the 1987 Nobel Prize for Economics, given to Robert Solow, the committee wrote: “Technological development will be the motor for economic growth in the long run.”

It, therefore, behooves us to seriously consider how nations should promote technological development. The basic tenet of the U.S. approach has long been for the federal government to fund basic research and let the commercial sector compete to develop technologies that benefit society, create jobs, and fuel economic growth. But is it really this simple?

In the days after World War II, when the U.S. had undisputed economic power and a massive lead in technology, monopolistic corporations with large research laboratories performed not only basic science research but also served as the north star that guided research toward commercialization. American industry’s giant lead in technology masked its underlying inefficiency in translating basic research into applied research. Corporations focused manufacturing on improving productivity rather than improving products to make them more competitive.

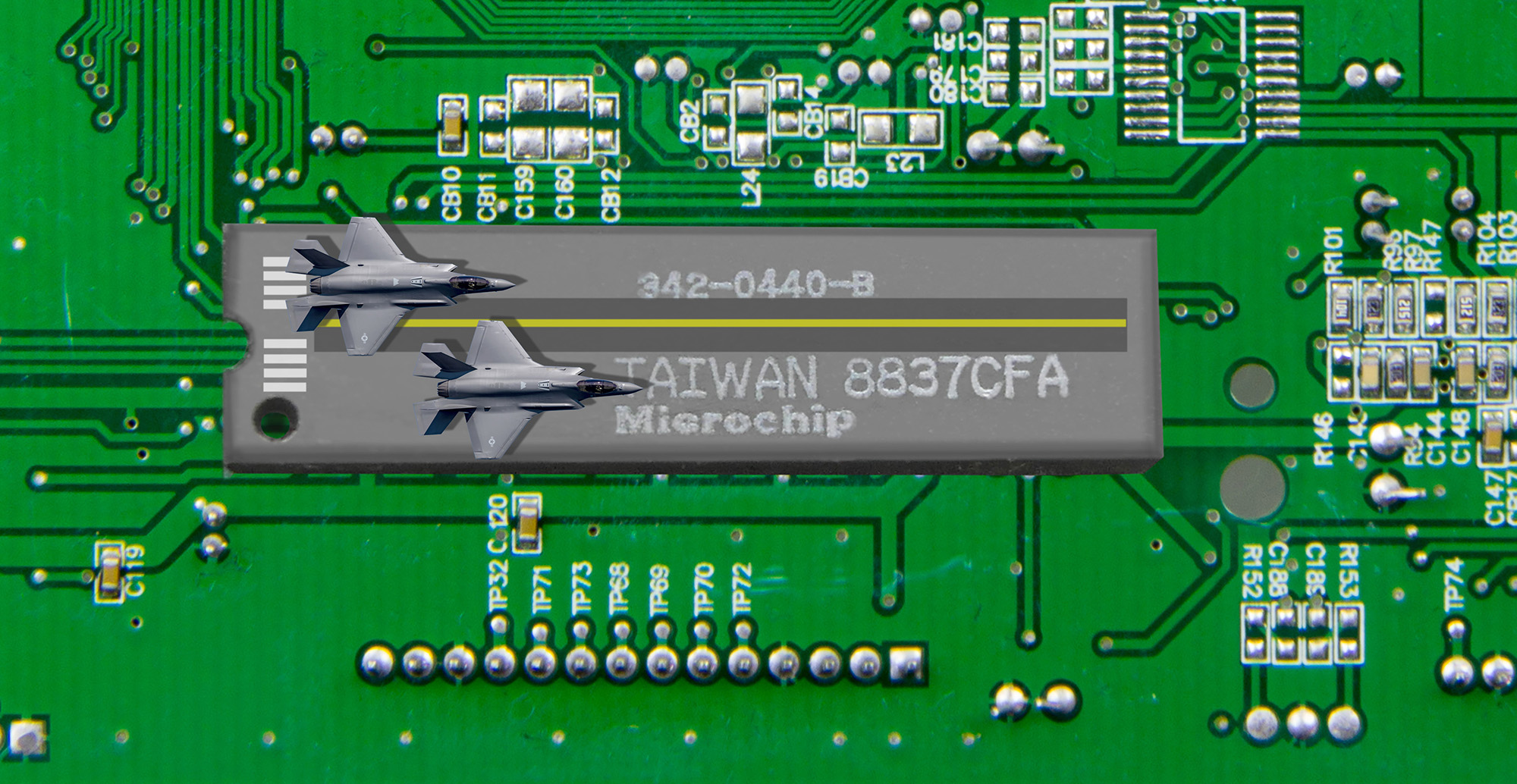

The world today is very different. Economic powerhouses bring competition to our shores: from China, India, Israel, Japan, Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, Vietnam, and Europe. Some competitors are allies and partners, sharing American values; others have different world views. Regardless, these competitors are not waiting for basic research to trickle down into technology products. They are actively nurturing technology development and fueling advancements in both manufacturing and technology products. They are building new supply chains and deploying their increasingly highly educated workforces to perfect the manufacturing process.

Without the ability to manufacture, no amount of research and development can bring competitive products at scale to the marketplace.

Manufacturing advanced technology products, such as semiconductor chips and batteries, is not just about churning out the same thing repeatedly without change. Innovations in materials, processes, and design driven by lessons learned on the manufacturing floor enhance product engineering every bit as much as design and product R&D do.

America may continue to bring home Nobel Prizes, but increasingly, others are building and scaling the technologies enabled by our inventions. Bridging the “lab-to-fab” gap, as touted by the 2023 CHIPS Act, is essential but not nearly enough. We have seen first-mover advantages such as flat-panel displays and electric vehicles slip away from our hands. Sustained technology leadership requires excellence in manufacturing at every level, from components to systems. Manufacturing as a discipline itself merits dedicated R&D and policy. This is nowhere more apparent than in the semiconductor industry.

We’ve seen this story before. The CHIPS Act is only the most recent federal initiative in a long line of efforts to secure America’s lead in semiconductors. Earlier programs like VHSIC in the 1970s and Sematech in the 1980s aimed to solve the same problem. And for a while, they did. But when attention and investment faded, so did the gains, opening up the field to our competitors.

Technology policy must, therefore, be approached not as a one-time fix but as an ongoing commitment. This includes crafting good policies that go beyond nurturing inventions and actively encourage domestic scaling. If invention is 10 percent of the process of building value and competitive advantage through technology, scaling is 90 percent.

Initiatives like the Microelectronics Commons, which aims to accelerate the passage of semiconductor innovation from lab to fab by building and sharing domestic prototyping facilities, are essential for success, as are programs for training and retraining the domestic workforce required for scaling. Creating a favorable scaling environment through deliberate ecosystem building, including the judicious application of export and import controls, rewarding scaling with special purpose tax credits, and removing overburdensome regulations are also critical success enablers, as is measuring whether scaling is working—and adjusting as needed when global competitors change course.

This is especially challenging in the U.S., where the default instinct is to let the market decide. But the market doesn’t optimize for long-term strategic outcomes—it prioritizes short-term profits. In mature industries like autos or chip manufacturing, the focus is on efficiency and margin; in newer industries like tech design, the focus is on breakthrough innovation. Both are necessary, but the incentives diverge.

In the global competition for technology leadership, what often separates the winners from the losers is the government’s determination to use every available tool to create and nurture both the invention and scaling ecosystems. That is the strategic challenge ahead.

Victoria Coleman was Chief Scientist of the Air Force during the Biden administration and Director of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) during the first Trump administration. She is now CEO of Acubed and Head of Research & Technology for Airbus North America. H.S. Philip Wong is a professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University and a former vice president of corporate research at TSMC, the world’s largest semiconductor foundry.