COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo.—Some of the Space Force’s biggest acquisition reforms have made their way into the service’s new nuclear command, control, and communications satellite program, the officer in charge of the effort said April 8.

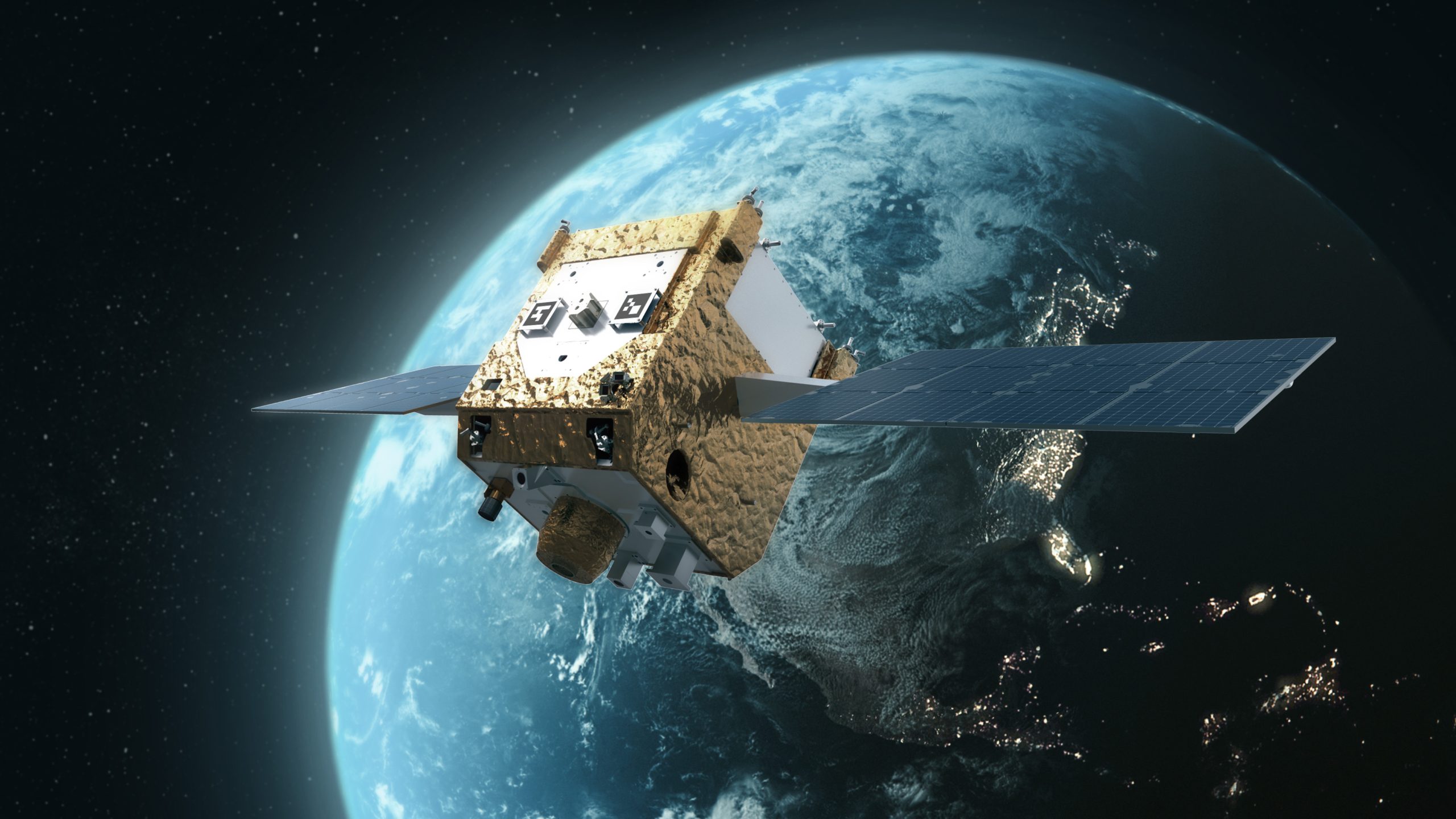

Evolved Strategic SATCOM is one of the biggest pieces of the Space Force budget, set to replace the Advanced Extremely High Frequency constellation. Fielded mostly in the 2010s, AEHF is one of the last programs with an old-school approach to space acquisition: just six spacecraft, each the size of multiple school buses and weighing more than six tons, with software for the ground control stations delivered after first launch.

In recent years, the Space Force has shifted toward buying larger numbers of smaller spacecraft with “commercial off the shelf” components, and former acquisition czar Frank Calvelli pushed programs to have their ground segment ready to go before the satellites launched.

ESS is embracing that shift, Col. A.J. Ashby, senior materiel leader for strategic SATCOM, told reporters at the Space Symposium, starting with where its satellites will fly.

“ESS will have a proliferated architecture, unlike AEHF,” he said. “AEHF is currently just in the geostationary orbit, and so we’ll be proliferated. We’ll be in diverse orbits, and there’s certain threats that we will address. But the most significant thing about ESS is that we’ll be able to service an increased number of strategic users that the current system doesn’t currently support.”

Space Force leaders have touted proliferation as a way to make targeting harder for potential adversaries, challenging them to find different ways to attack objects in different orbits and narrowing the target window as spacecraft move relative to the Earth.

The exact number of satellites in the ESS constellation remains a secret. Space Force budget documents reference the need for four space vehicles to achieve initial operational capability by fiscal 2032, but Ashby declined to comment further than that.

Who exactly will build those satellites is still to be determined—the program is in source selection, with Boeing and Northrop Grumman as the top contenders after building prototypes. Ashby also declined to say when a contract might be awarded.

However, Ashby did suggest whoever does win the contract won’t necessarily be building the exquisite systems that have defined strategically vital programs in the past. While there is no commercial market for nuclear command, control, and communications functions, existing commercial components and parts could be useful.

“Spacecraft buses, we’re taking a hard look at that,” Ashby said. “With regard to crypto, we’ve got Viasat, we’re on contract with ViaSat right now for their chassis for our cryptographic units. Those are commercial products, right?”

There are limits to how much commercial can be used for the program. Asked if SpaceX’s massive Starlink communications constellations is being considered for any part of the ESS requirement, Ashby said, “Not right at this point in time.”

On the ground, though, ESS will embrace a commercial-like approach. Back in 2023, the Space Force awarded a contract to Lockheed Martin for what it calls the Ground Resilient Integration & Framework for Operational NC3, or GRIFFON, but Lockheed won’t be the only contributor.

“You kind of liken the framework to your cell phone, and then you have different applications that would ride on that framework,” Ashby said, explaining that Lockheed will build the framework and then allow smaller software developers to work within that framework.

“We have the best of breed, so leveraging the software acquisition pathway, we’re leveraging the Space Enterprise Consortium, other transaction authorities, we’re able to put the best of breed of software developers on contract to do that,” he said.

That approach is one borne out of hard lessons learned from other ground segments the Space Force has tried to develop all at once, only to encounter years of delays that have limited satellites’ capabilities.

The Space Force has outlined plans to spend $5.11 billion in research and development on ESS from 2025 to 2029, making it one of the service’s biggest programs.