At the Space Symposium on April 8, Vice Chief of Space Operations Gen. Michael A. Guetlein and National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency Director Vice Adm. Frank D. Whitworth appeared on panel together touting their successes and addressing common concerns.

Since the stand-up of the Space Force and its inclusion in the Intelligence Community, there have been questions about its relationship with the likes of the National Reconnaissance Office and NGA.

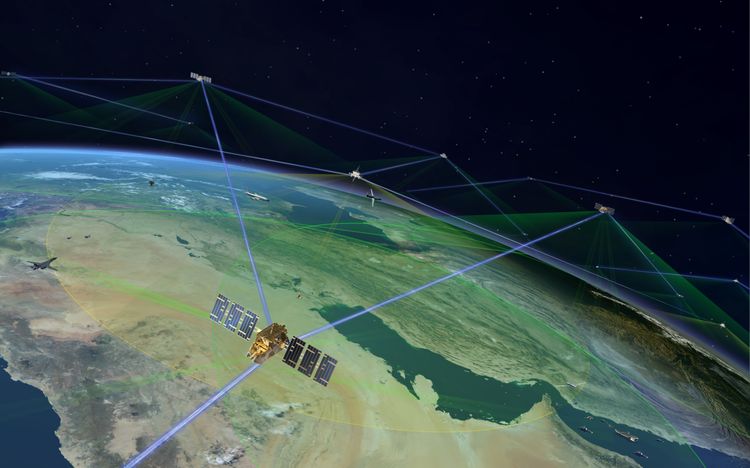

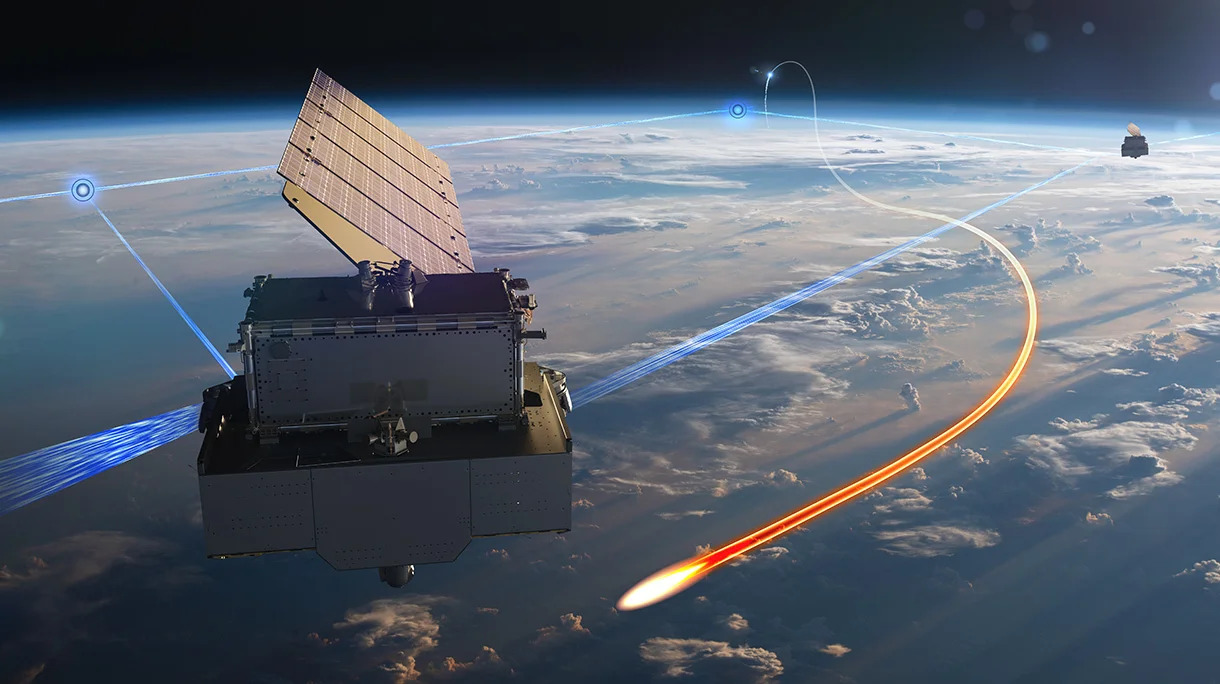

For years, the NRO has used satellites to collect imagery and signals intelligence, and the NGA has analyzed that data to produce intelligence products. Now the Space Force is doing more and more intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance from orbit, with the goal of delivering tactical and operational intel to warfighters.

Space Force proponents have argued the NRO and NGA are focused on high-level strategic missions and can’t provide intelligence data quick enough to the battlefield. IC proponents say the agencies have decades of experience performing their missions and serve a critical function by making sense of the vast amounts of data coming from space.

During the panel, Guetlein emphasized that the Space Force doesn’t want to duplicate existing NGA efforts, whether that’s buying commercial analytics or organic analysis.

“I would much rather go copy what they’ve already done and build upon that in a collaborative manner than have to go recreate all that technical capability from scratch,” he said.

For his part, Whitworth said the NGA is working on accreditation for models to alert combatant commanders and provide them with verified, reliable intel on faster timelines, and he asked for patience as they do so.

“The reason that we do this is not to centralize. It is actually to decentralize,” he said. “And so when I ask for this patience, please remember that we’re trying to establish that standard so that you can move quickly, ensuring that prerogative of the Commander-in-Chief and of the SecDef and of those combatant commands is preserved all the while. It will help speed.”

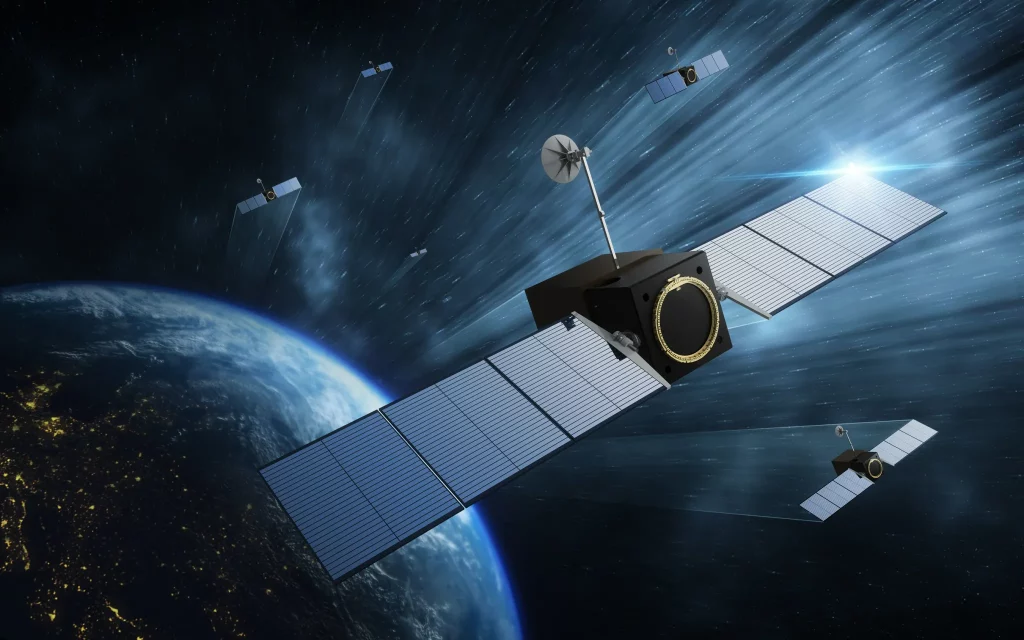

One of the biggest sticking points in the Space Force’s relationship with the NRO and NGA has been who should be the one buying ISR imagery and services from commercial space companies.

While the NRO has bought commercial imagery and the NGA has bought commercial analytics for years, the Space Force is getting in on the game too, largely through the Commercial Space Office and its Tactical Surveillance, Reconnaissance, and Tracking program, or TacSRT.

Guardian leaders have praised the TacSRT program as a major success. It acts as a marketplace for operators to essentially buy surveillance-as-a-service from commercial companies for specific missions on rapid timelines. And Congress likes it too, dedicating $40 million for the program in its latest appropriations bill.

With so many different government organizations buying commercial products and data, however, there is the inevitable risk of some buying the same thing.

“We work really closely with the NRO on the access to commercial data, to make sure that we’re not buying the data twice,” Guetlein said. “We work really closely with … NGA to make sure on the analytics side, I’m not duplicating that effort, that if I’ve already got the data coming down from [government satellites], I’m not going off and rebuying it.”

Not duplicating efforts is one thing. Coordinating them to maximize time and money spent is another. Col. Rich Kniseley, head of the Commercial Space Office, said his team is working on an agreement with the NRO to improve their teamwork.

“The agreement is in the final stages of approval,” Kniseley said in a statement. “The agreement provides a mechanism for the NRO and COMSO to utilize each other’s contracts as well as transfer funds between organizations.”

Breaking Defense first reported on the agreement.

Still more agreements may be coming—Guetlein said the Space Force, NRO, and NGA are “putting in place the programmatic structures to jointly go buy these capabilities together, to govern these capabilities together, then looking at legally, how can I distribute the data?”

Whitworth said NGA is helping the cause with its Joint Mission Management Center, which brings together services, combatant commands, and other intelligence agencies to make sure everyone’s on the same page.

“No matter what you have in the way of memoranda of agreement, or any sort of interagency agreement that might be where we’re going to go … you’ve got to have a place where everybody works together,” Whitworth said.

The JMMC, which has reached initial operational capability, is that place, agreed Whitworth and Guetlein. In the long term, Whitworth said he actually hopes the center gets smaller due to automation and established lines of cooperation. More immediately, however, he said his priority is to get more Space Forces members into the center and working with the NGA more broadly.

“More Guardians at NGA—this is something we’ve talked about, and it’s already happening,” Whitworth said. “So this has already been realized. The JMMC is for real. It is now in its initial operating capability status, and there are plans for even more Guardians to be there.”

Guetlein, for his part, said the center and the other agreements in the works are setting up a massive change in the relationship between the military and intelligence community.

“I think what you’re going to see is—not five to 10 years from now, I think it’s two to three years from now—a seamless integration of Title 10, Title 50, a sharing of data like we’ve never seen before, a common operating picture that we’ve been trying to chase my entire career.”