The first day back at work wasn’t supposed to go like this. The 121st Fighter Squadron had returned on Saturday from a Red Flag deployment in Nevada; Monday was a day off.

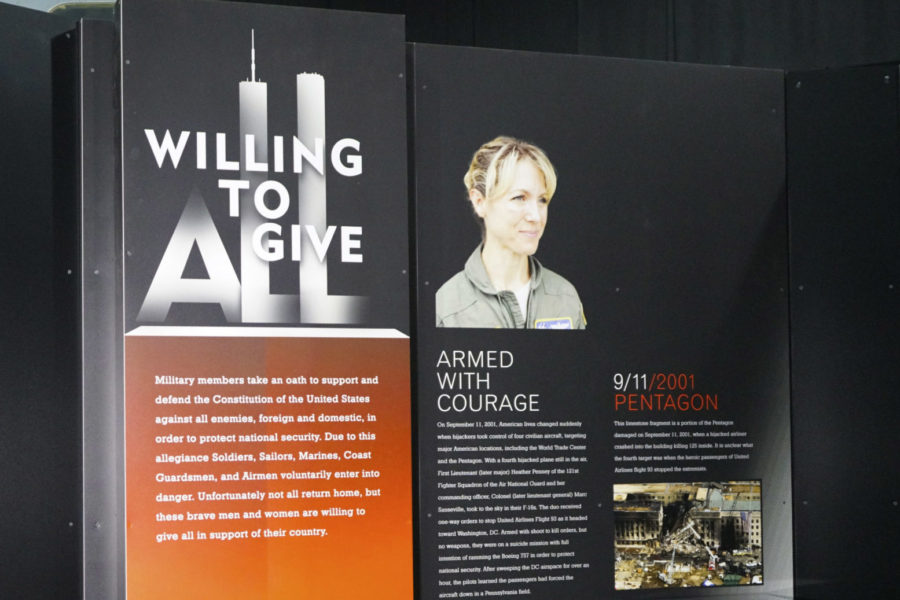

Now, on Tuesday, District of Columbia Air National Guard squadron leaders were meeting at Andrews Air Force Base, Md., to set training priorities. Heather Penney, a green first lieutenant, was in the meeting because her secondary duty was squadron training officer.

The session was interrupted when someone opened the door a crack to let the assembled officers know an airplane had flown into the World Trade Center.

“And we all looked outside, and it was a crystal-clear, blue September Tuesday morning,” Penney recalled. The weather was likely the same in New York, and the pilots speculated that either “someone totally pooched [fouled up] their instrument approach,” or some small aircraft sightseeing on the Hudson had made a really bad turn.

The group returned to its meeting. A short while later, the door was opened again, this time wide, and a noncommissioned officer said a second aircraft had flown into the WTC, “and it was on purpose.”

With urgency but professionalism, the group looked at each other and asked, “What do we do now?”

Over the following hour, unit leaders tried to get orders to act. While state Air Guard units get instructions from their governors, D.C. has no governor, so the Guard takes orders directly from the President. Further, the base was not an alert facility, so it was not tied in with the North American Aerospace Defense Command. The Secret Service has a heavy presence at Andrews, however, because it is the operating base for Air Force One.

Brig. Gen. David F. Wherley Jr., 113th Wing commander, ordered his Airmen to begin preparing for a possible launch. He called his Secret Service contacts, seeking authorization for an improvised combat air patrol mission.

As they hurried to pull on their flight gear in the life support shop, Penney and her flight lead, Maj. Marc Sasseville, had a perfunctory conversation about what they would do if they found the inbound airliner they had been told was on its way toward Washington.

They would be launching with nothing on board but about 100 rounds of training ammunition—simple bullets with lead tips, not the usual 20 mm high-explosive incendiary rounds used in combat. AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles were being unpacked and built up at Andrews’ weapons area, but it took time to assemble the missiles, and the cart that transported them from the far side of the base moved at a top speed of just nine miles per hour. The Sidewinders would have to wait for a second flight.

Penney, remembering an accident investigation that her father had participated in, recalled that 737s simply dropped from the sky if they lost their tails, leaving “a very tight debris field.”

The mission here would be to bring the airliner down causing as few casualties as possible on the ground, but primarily to make sure that it did, indeed, crash without reaching its target.

The training ammunition wasn’t going to be enough to do the job, Penney explained, “even if you’re a perfect shot.” There was really only one way to take down a large airplane under these circumstances.

“Fly into it,” Penney said.

Sasseville said he would ram the cockpit; Penney intended to take out the tail. “I know for sure that if I take off the tail, that it will just go straight down,” so she intended to “aim the body of my airplane” at the empennage.

Penney was hoping to have enough time to eject after the impact, but was keenly aware that she’d have to stay with the F-16 until it struck the airliner.

“It was very clear that, yeah, this was”—Penney declined to finish the thought—probably going to be a one-way mission.

Wherley soon received orders from the Secret Service to intercept any approaching aircraft and keep them away from an eight-mile circle around downtown. “That allowed an ROE-build,” said Wherley in a 2004 interview, referring to rules of engagement.

Penney and Sasseville powered up immediately.

Normally, an F-16 preflight took 10 to 20 minutes. Now, she and Sasseville were rolling within seconds; the crew chiefs were “still under the jet, pulling pins” even as the fighters surged forward, she said. In two minutes, at full afterburner, they were airborne.

It was about 10:40 a.m., just an hour after American Flight 77 had struck the Pentagon, and Sasseville and Penney knew they had a grim mission. At least one airliner was still believed inbound toward Washington, D.C. Their job was to get over the city as soon as they could and act as the “goalie” CAP: to bring down any aircraft ignoring orders to turn away.

As Sasseville and Penney screamed skyward, banking toward the Potomac River and Washington, Penney said the whole scene was dream-like. In the center of an extremely congested triangle of commercial airports—Reagan National and Dulles in Virginia, and Baltimore-Washington in Maryland—D.C. was typically abuzz with airliners, business jets, and general aviation airplanes. Sometimes, it could take two minutes to get departure clearance from Potomac Control—an eternity in a gas-guzzling F-16.

By midmorning on 9/11, however, nothing else was up. “It was eerily silent,” Penney recalled. “That part was very surreal.”

Sasseville and Penney flew over the Pentagon, then proceeded west-northwest, as instructed, looking for the inbound airliner. In the confusion of the morning, they were looking for United Airlines Flight 93, which, unknown to them, had already crashed in Shanksville, Pa.

F-16s from the North Dakota ANG soon arrived and also took up station, having flown up from Langley Air Force Base, Va. The D.C. and North Dakota F-16s set up a high-low CAP, with the Fargo jets staying above 18,000 feet, looking for inbound threats from over the ocean, while Penney’s flight stayed low, on the lookout for threats trying to sneak in at low altitude, as the previous attacks had done.

Because they had been dispatched by NORAD, the Fargo Vipers were joined by a tanker, and all the F-16s over Washington took turns refueling.

They remained up for four hours, and when Penney and Sasseville landed back at Andrews they left plenty of other interceptors over the city. Upon landing, they were whisked to a room “with more generals than I’d ever seen in my lifetime,” Penney said.

“We stood at the head of an oval table in front of the entire group, and it was standing room only, and they asked us all sorts of questions about the morning and the sorties, and what we had seen,” she said. It was heady stuff for a first lieutenant who had only been assigned to the base for nine months.

Almost immediately, the two F-16s relaunched—now fully armed—to fly another four-hour mission over the capital.

During this second sortie, they received instructions over the encrypted radio to escort Air Force One, which was inbound on its way to Andrews. “I then flew point, leading the package back,” Penney said. “The first sortie, we were far more focused on doing the task at hand,” she said. Hours later, it was still “hard to believe” what had happened.

Penney spent some of the time on the second sortie above the Pentagon, looking down at it with her jet aircraft’s infrared targeting pod, trying to get the events of the day to seem more real.

The D.C. Air Guard served as Washington’s CAP resource for the following two weeks, but of the 32 pilots assigned to the unit, only about eight were full-timers. Many of the traditional Guard pilots were airline pilots “stuck in different parts of the country” when air travel was abruptly halted on 9/11. For the D.C. Guard, the air defense mission represented “24-hour operations with decreased manpower,” Penney said, “very work intensive.”

The situation didn’t leave much time for reflection. While it was a “dramatic experience,” she became turned off by “the melodramatic media attention,” and postponed much personal reflection.

“I really didn’t process or think through all of that until a couple of years ago,” Penney said. However, as to the notion of having to take down an airliner with innocents aboard, “it was so abundantly clear in the moment that, while it would have been tragic and unfortunate, the moral choice was obvious.”

She said that at no point “did I feel conflicted, like, ‘Could I really do this?’”

The “total heroes” of the air action, she said, were the passengers on Flight 93 who ultimately made the goalie CAP unnecessary.

“What they did was courageous,” Penney said. “And I think for them it was also obvious, once they realized what was going on.”

Editor’s Note: Heather Penney is now a senior resident fellow at AFA’s Mitchell Institute for Aerospace Studies. This article originally appeared in the September 2011 edition of Air Force Magazine.